All roads in jazz lead to Duke Ellington, and Ellington is himself a subject of nearly endless proportions. Duke has been known to seduce people-- dancers, actors, musicians, intellectuals, and regular Joes alike-- into a lifetime of listening.

I'm one of those Joes. I recall a period of about seven years, from about 1979 until 1986, when nothing but Ellington was good enough for me to hear. Coming out of this fool's paradise was no easy task; eventually I realized there was a whole world of music outside Ellingtonia. But the melody still lingers on.

This piece was written in 1988 for a class on film theory; I apologize in advance for any jargon (diegetic, supradiegetic) left over from that last academic tour, not to mention typos or plain bad writing. I've thought about putting this item into print and, in recent years, sent it off to a snazzy European jazz journal I won't name, only to be rejected summarily by an editor I also won't name.

Nonetheless, I've never seen anything better written about this particular corner of Ellingtonia, so I let my ego get the better of me and painstakingly have retyped it here. I expect to do something similar, but I hope not as demanding, with other stuff I have already written before it all goes after me into the Great Abyss.

In addition, I must mention two excellent sources I have seen since completing this investigation: Duke Ellington: Day by Day and Film by Film, by Klaus Stratemann (JazzMedia, 1992), and Dudley Murphy: Hollywood Wild Card, by Susan Delson (U. Minnesota, 2006)

Please take a moment to enjoy the film:

Black and Tan, dir. Dudley Murphy, 1929

We hear the music first. It travels the distance from foreboding Crescent City dirge to playful, striding Harlem rent-party shout to flat-out, gutbucket blues. A solidly built young man in vest and shirtsleeves sits at a plain, upright piano, a cigarette between his lips. We see only his back at first, and then an occasional glimpse of a handsome, dark-hued profile, as he turns left to explain the chord changes and orchestration of the new piece he is playing to a younger and fairer gentleman wearing a hat, who sits attentively upon a chair and holds a trumpet. The urbane pianist, Duke Ellington, and his sideman Arthur Whetsol are re-enacting history to create myth.

They are playing themselves as they were decade back, teenaged apprentice musicians in Washington, D.C., visiting each other's homes to rehearse a new number, unselfconsciously at the leading edge of a generation of middle-class black entertainers and intellectuals who would transform American culture over the next twenty years. By 1929, Duke Ellington and His Cotton Club Orchestra, in terms of national fame and show-business clout, were the preeminent black musical aggregation in the world.

In the film's opening sequence, the number being rehearsed is the "Black and Tan Fantasy," the composition that best defined the parameters of Ellington's signature "jungle"style, a bridge between African and European culture and quite likely the inspiration for the first "serious" treatises in America on jazz as an art music:

"When [Irving] Mills stepped in, accident and chance stepped out; big business took over, and the rise of the Ellington orchestra was made inevitable," (2) wrote Barry Ulanov. While not quite so automatic a guarantee of success as this would have it, the unique partnership between manager-publisher Mills and Ellington-- Jewish businessman and Negro musician-- would be decisive for the dominant role Duke Ellington would play within the black entertainment world throughout the 1930s. Upon first hearing the "Black and Tan Fantasy" in Ellington's audience at the Club Kentucky in 1926, Mills would write many years later,

I immediately recognized that I had encountered a great creative artist-- and the first American composer to catch in his music the true jazz spirit... Shortly after that, when I was producing a new show for the Cotton Club, I built as much of it as possible around Duke's band and his music... I had complete faith in Duke Ellington and firmly believed that together we were launching something more than just a dance orchestra. I was convinced that we were launching a great musical organization especially designed to interpret something new and great in American music: the music of Duke Ellington. (3)

With the new development of sound-cinema, Mills-- having put Duke over in Harlem, on Broadway, on myriad recordings, and over the national airwaves-- was eager to market him in screen appearances across the country, in effect making Duke Ellington, along with Paul Robeson, one of only two black leading men backed by a major film studio. The following year, Ellington would score his first great crossover to the mass market with "Mood Indigo."

At the same time, the late 1920s were the site of origin by what Harold Cruse calls the "ethnic war for cultural supremacy" between Negro and white in the burgeoning American mass media. If the intention of the Ellington-Mills partnership was to open the doors of American show business to the groundswell of New Negro entertainment, its result was something quite different. Ellington and precious few other Negroes would step over the race line to the glory of mainstream showbiz; instead, the vast reservoirs of black talent would remain subordinate to the whims of white entertainment brokers in Hollywood and New York, a sort of cultural imperialism on guard against a black revolt whose meaning was understood implicitly:

... Negro entertainment posed such an ominous threat to the white cultural ego, the staid Western standards of art, cultural values and aesthetic integrity, that the entire source had to be stringently controlled. (4)

The vertical consolidation of the American entertainment industry-- in 1927 Wall Street had knit RCA, the Keith Orpheum theater circuit, and Victor Records into a cost-efficient chain of production and distribution-- thus coincided with the emergence of the New Negro into national consciousness, and throughout the 1930s Hollywood would amalgamate the entire industry into its own juggernaut.

Black and Tan was filmed at RCA's sound studios on East Twenty-fourth Street in the Gramercy neighborhood of New York, for a December, 1929, release. There is some question about the actual date of filming, usually given as February 1929; discographer Benny Aasland, however, puts the date at July, while the Ellington band was engaged at the Ziegfeld Theatre in Show Girl. (5) In any case, following the logic of its constituent corporate mergers, RKO set to work joining the technologies of record sound and the cinematic image. Early in 1929 they devised a new sound-on-film (optical sound) system which was trademarked Photophone, a vast improvement over the old Movietone sound-on-film method. The Photophone system, pioneered in musical shorts such as Black and Tan, quickly replaced the sound-on-disc Vitaphone technology throughout the movie industry. The new studios, from their inception, were working practically 24 hours a day, seven days a week, on a very tight schedule. (6)

*

Whether or not the long take of the piano player's back in the opening scene was a device to mystify Ellington's persona, its technique did try to make the most of sound-studio technology still in its infancy. On one level, we can view the film as a technician's experiment in glitz to cover the gaping problems posed by synchronous editing with a "live" music track. Here it must be understood that Black and Tan displayed a rare respect for a black musician in its treatment of Ellington's music; in doing so, the film achieves a sense of equality between image and sound, a genuine counterpoint between music and narrative seldom attempted in Hollywood musicals. Because cinema had not yet developed a satisfactory means of dubbing the soundtrack independent of the visual image, however, the use of prerecorded music, essential technology for the Hollywood musical of the future, was not available to Black and Tan. The sound camera was in 1929 still a stationary sweatbox, and to maintain "live" musical continuity through cinematic cuts required the crowding of soundstages with multiple cameras. Writer-director Dudley Murphy, in effect, walked a tightrope between the integrity of Ellington's music and the restrictions such integrity placed upon the choices he could make as a filmmaker.

How sophisticated was the Hollywood musical in 1929? To judge by the standards of Rick Altman, the most thoroughgoing of the genre's theoreticians, it had evolved a great distance since the crude Vitaphone part-talkie The Jazz Singer had told the world, "You ain't heard nothin' yet." Clive Hirschhorn profiles more than fifty feature-length movies released between 1927 and 1929 (principally by Warner, MGM, Fox, Paramount, RKO, Columbia, Pathe, and First National), which could be described as musicals, at least in the sense of the genre's "semantics" described by Altman. In the sense of film-musical "syntax" (i.e., its higher-level functioning), however, these films-- the crest of the American film musical-- are less assured of being admitted into Altman's generic corpus.

Altman's theory is founded upon sexual dichotomy, the idealized courtship ritual characteristic of the American film musical. Its paradigmatic structure is a dual-focus narrative of paired segments whose parts recapitulate the duality of the whole. The primary sexual duality overlays a variety of secondary dualities (rich v. poor, past v. present, work v. play, etc.) which are mediated as marriage resolves the fundamental dichotomy. The film musical demonstrates a unique grammar of audio- and video-dissolves, which diegetic music mediates between the diegetic (background) soundtrack and a supradiegetic music track to establish, in its key sequences, the primacy of the audio track, a reversal of the conventional cinematic image/ sound hierarchy.

The musical "freezes" its narrative into the rhythms of diegetic music. The foregrounding of certain secondary motifs establishes the theory's three major subgenres: fairy tale, show, and folk musicals. The technical limitations of 1920s sound film introduce a wrinkle into Altman's theory: the fully-developed film musical syntax of the genre's golden years-- particularly the dual-focus narrative structure, Altman's sine qua non-- is present in the prototype musicals of the early sound period, but generally only in incomplete, fragmented, developmental fashion. Somewhat arbitrarily, part-talkies like The Jazz Singer are included in Altman's corpus, while, because it is not a full-length feature, Black and Tan is excluded. Manifestly closer to the generic paradigm Altman wishes to establish than many of the films he chooses for illustration, Black and Tan is nevertheless banished beyond the margins of the American film musical, and thereby a significant insight into the historical development of generic semantics and syntax is overlooked.

Writer-director Dudley Murphy was born in Winchester, Massachusetts, in 1897. A career in journalism led to his first ventures in film as a cinematographer in his early twenties. While Murphy's American silent film credits from 1923 to 1928 (High Speed Lee, Alex the Great, Stocks and Blondes) were generally undistinguished, in 1924 he arrived in Paris to make important, though generally unrecognized, contributions to the French avant-garde in collaboration with Cubist painter Fernand Léger, Ballet Mécanique in that same year.How sophisticated was the Hollywood musical in 1929? To judge by the standards of Rick Altman, the most thoroughgoing of the genre's theoreticians, it had evolved a great distance since the crude Vitaphone part-talkie The Jazz Singer had told the world, "You ain't heard nothin' yet." Clive Hirschhorn profiles more than fifty feature-length movies released between 1927 and 1929 (principally by Warner, MGM, Fox, Paramount, RKO, Columbia, Pathe, and First National), which could be described as musicals, at least in the sense of the genre's "semantics" described by Altman. In the sense of film-musical "syntax" (i.e., its higher-level functioning), however, these films-- the crest of the American film musical-- are less assured of being admitted into Altman's generic corpus.

Altman's theory is founded upon sexual dichotomy, the idealized courtship ritual characteristic of the American film musical. Its paradigmatic structure is a dual-focus narrative of paired segments whose parts recapitulate the duality of the whole. The primary sexual duality overlays a variety of secondary dualities (rich v. poor, past v. present, work v. play, etc.) which are mediated as marriage resolves the fundamental dichotomy. The film musical demonstrates a unique grammar of audio- and video-dissolves, which diegetic music mediates between the diegetic (background) soundtrack and a supradiegetic music track to establish, in its key sequences, the primacy of the audio track, a reversal of the conventional cinematic image/ sound hierarchy.

The musical "freezes" its narrative into the rhythms of diegetic music. The foregrounding of certain secondary motifs establishes the theory's three major subgenres: fairy tale, show, and folk musicals. The technical limitations of 1920s sound film introduce a wrinkle into Altman's theory: the fully-developed film musical syntax of the genre's golden years-- particularly the dual-focus narrative structure, Altman's sine qua non-- is present in the prototype musicals of the early sound period, but generally only in incomplete, fragmented, developmental fashion. Somewhat arbitrarily, part-talkies like The Jazz Singer are included in Altman's corpus, while, because it is not a full-length feature, Black and Tan is excluded. Manifestly closer to the generic paradigm Altman wishes to establish than many of the films he chooses for illustration, Black and Tan is nevertheless banished beyond the margins of the American film musical, and thereby a significant insight into the historical development of generic semantics and syntax is overlooked.

*

Ballet Mecanique

For the next decade-and-a-half, however, his career in Hollywood set him to work on a series of pedestrian and mostly forgettable film projects (Jazz Heaven, 1929; Confessions of a Co-Ed, 1931; The Sport Parade, 1932; The Night Is Young, 1935; Don't Gamble With Love, 1936; Main Street Lawyer, 1939; One Third of a Nation, 1939) which afforded him few opportunities to further explore the experimental techniques he had developed with Leger.

Along the way, however, Murphy wrote and/ or directed a few specialty films within the submerged genre of African-American cinema. Black and Tan was his second voyage on what proved to be a fruitful mini-career directing black casts for the screen, his debut effort having come earlier in 1929 with Bessie Smith's only film appearance in St. Louis Blues. In 1933 he directed Paul Robeson in a highly stylized version of Eugene O'Neill's The Emperor Jones.

In 1929 the race theme in American movies, reflecting the segregation of the cinema audience, was more problematic than in the post-civil rights epoch (in which both black screen images and their audience distribution are relatively homogenized, racially speaking). A black "underground" film industry which catered exclusively to ghetto audiences had grown up during the silent era, but by 1929 the expense of sound technology and the onset of the Depression combined to drive black filmmakers out of business, with the significant exception of Oscar Micheaux. The coming of sound put the black underground movement into its second phase, wherein Hollywood studios, along with their well-established genres, stepped into the ghetto market. (7) Here, in a curious recapitulation of the layered structure of American mass culture, the white auteur presented a black milieu, which was distorted by traditional race stereotyping to be consumed by a segregated black audience. Hollywood's attempts that year to reach the mass audience with the Negro musicals Hearts in Dixie (Fox) and Hallelujah (MGM/ King Vidor) had been unsuccessful, and the next full-length Negro musical feature, The Green Pastures, would not be released until 1936.

Yet Black and Tan's audience remains unclear (in the multiple context of apparatus, genre, and technique), producing an ambiguity that underlines the primacy of the interpretive community in the determination of meaning. This ambiguity is all the more urgently felt in a movie designed to create a star mystique around Duke Ellington. From our present point of view, the mysterious figure at the center of the film acquires additional layers of indeterminacy, tantalizing to the theorist. Stars, stock market mergers, and nearly a century of hindsight combine to produce a nineteen-minute chiaroscuro.

*

Black and Tan's narrative structure, like Ellington's "Fantasy" itself, formed a triptych. Two "natural" scenes flank a choreographed night at an all-Negro revue. The narrative proper begins with a cut from Ellington and Whetsol to an exterior insert-shot of two very black men entering a building, as the music, led by Whetsol's high C, sustains a single blues chorus.

At this point the race genre takes over: the racial subtext of early Hollywood cinema here becomes the main text. As in earlier films, myth uproots history, but here a bold, new element subverts one race myth and substitutes a more modern one. Duke Ellington is the educated, mannered Negro intellectual beloved in Harlem's heyday. He plays against traditional Negro stereotypes prevalent in American show business since the 1840s: coons, toms, and the tragic mulatto, as well as the nineteenth-century heritage of Afro-American music (the spirituals at the end of the film are transformed from black to "black and tan"). In addition, at the film's climax Ellington confronts his white boss in a manner that would have ended up on the cutting-room floor had this been a full-length feature film. The general idea seems to have been to mythologize Duke Ellington as a black Jack Armstrong.

Moving men: Alec Lovejoy, l., and Edgar Connor

As the camera cuts to the building's hallway, dialogue introduces the "coon" comic movers, Edgar Connor and Alec Lovejoy (who are not identified in the film credits), a Mutt-and-Jeff pair, both fitted with ridiculous hats, one lazy and the other just plain dumb. Only the little patsy character is given a name, or rather names, for he is addressed by his partner variously as "Action," "Eczema," "Estes," and "Sasparilla." Their routine is supposed to be a comic revelation of low-down, scuffling Negro illiteracy, a subject of special significance to black audiences.

Dolly back and cut to the room interior, where Duke has resumed his duet with Whetsol. Here the room is revealed in long-shot to be a tiny flat containing a piano, bed, sink, and a single chair. The ensuing dialogue clarifies the syntax based upon black audiences a film market. Sympathy (and thereby audience identification) is focused upon Ellington with his line, "You're not going to take the piano?" This serves as occasion for riposte straight out of Negro vaudeville-circuit burlesque: "I ain't coming' for your icebox." Racist dialect jokes ("You ain't paid nothin' on this piano since last Octuary") widen further the bifurcation between the New Negroes and the coons.

The film's tragic mulatto is sexy Fredi Washington, the the object of adulation in black gossip columns. She developed the mulatto role to perfection in her Hollywood films of the 1930s, most notably as Peola in the original Imitation of Life (1934). In Black and Tan audiences may very well have taken her for white (which obviously would add another dimension to the movie's resonance), but the subject of race never enters the dialogue of this race film. Of more audience interest, probably, is Fredi's look of desire, with which the image of Duke Ellington begins to dominate: Arthur Whetsol, momentarily, ceases to exist (even though he is clearly on the set), returning only at the end-of-scene reprise of the "Black and Tan Fantasy."

Fredi bursts into the room, as if walking on air, with "wonderful news." She tells Duke she has found a nightclub job for both of them, and then sees the movers and pins the situation. This sets up the coon business scene with Fredi: they won't accept a cash bribe to tell their boss no one was home, but a bottle of gin suffices to seal the bargain (a Prohibition era rendition of the "Massa John" tales in African-American folklore?). Ellington arches his famous eyebrows. doing his best to look bemused in the background of a three-shot. His wooden acting suggests he could never play any part but Duke Ellington. This stagy scene is hastened along by cuts, mainly alternating between a medium shot of Fredi pouring the booze in a corner and a tight three-shot of more coon foolery at center. The movers leave with Fredi's bottle of gin.

"Gee, I'm glad that's over with," sighs Fredi as she eases her body against a doorpost. We wait an eternity for Duke to pick up his cue and arrive for the two-shot: "But you know, Honey, we can't take that job. What about your heart?"

|

| l. to r.: Arthur Whetsol, Fredi Washington, Duke Ellington |

"Oh, don't bother about my heart," Fredi tosses back, as they drift back to Whetsol and the piano, in a near-return to the opening shot. At a slightly different angle and with Fredi standing at center, behind the piano, the "Black and Tan Fantasy" takes flight with her imagination.

*

In essence, black and tan mythology-- the Cotton Club fantasy-- expresses the sophistication of the white tourists and intellectuals, from Rotary conventioneers to Carl Van Vechten, who since 1921 had invaded the cabarets of Harlem, promoted and plundered her cultural "renaissance," and staked out the ringside seats on their own, whites-only, pleasure island in the land of the darkey.

The etymology of the term "black and tan," according to at least one jazz historian (8), can be traced to a certain nineteenth-century "low-life" club in Greenwich Village, the Black and Tan. This cabaret reportedly catered to a clientele of black men and white women and featured "the cancan and licentious displays." It is reasonable to suppose that the term "black and tan" rests on precisely this racial/ sexual dichotomy, tor the black and tan show's principal signifiers, in effect, were patterns and shades of skin.

|

| Duke Ellington and His Cotton Club Orchestra |

"The Duke Steps Out": piano chords (the link to the preceding scene) introduce a shot of Ellington's hands at the keyboard. The camera pulls back quickly to reveal in succession the immaculate leader's gaze, his tuxedoed orchestra, a curtained proscenium, a tuxedoed dance quintet (the Five Hot Shots) doing an intricately choreographed, semi-acrobatic tap routine, and a mirrored floor. For the greater part of this scene, the viewer occupies a seat in the filmic audience, watching a portion of a show very much like the one the band was performing every night at the Cotton Club. We seem to be at the boundary between savagery and civilization, between the old plantation (unlike the film, the Cotton Club set invoked a fantasy world of slave cabins and boll weevils) and the New Negro.

|

| The Five Hot Shots |

The Ellington musical genres themselves grew out of the pragmatic parameters of the Cotton Club show. The orchestra parlayed Ellington's formal and harmonic experiments into mood pieces for blue-lit romantic scenes. The needed accompaniment for the club's featured dancers and chorus line came in the form of flashy, show-stopping production numbers built around the showy, pyrotechnic drumming of Sonny Greer. To reassure and relax the audience, Ellington came up with ingenious arrangements for the well-known popular tunes of the day.

The Cotton Club show itself was more Broadway than minstrel, a Ziegfeld-style "multileveled, fast-paced revue... essentially an uptown version of the lavish Negro stage revues that were selling out theaters down on Broadway." (9) The shows, produced by Lew Leslie and written by Dorothy Fields/ Jimmy McHugh, Harold Arlen, etc., were the stuff of white folks' dreams, and Black and Tan admirably recaptures their essential iconography on film. Nearly all male performers are dark-skinned and garbed in tuxedo; the female roles, as Cotton Club custom dictated, were performed by light-skinned, "high-taller" women wearing costumes meant to suggest either jungle passion or bog-city vamp.

The interplay of white and black imagery is crucial to the scene; as the performance unfolds, the mirrored floor extends its rhythmic patterns across the screen. After a brief curtain, the male dance quintet shifts into the lilting "Black Beauty," ranked into a gentle close-order unison, causing the screen pattern atop emerge in bold black and white contrasts. The straight-ahead long shot from the audience position privileges these rhythmic patterns over the individual identities of the performers; the only closeups are of Ellington, gazing into the camera from his position at the piano. The band goes by in a quick blur, and the dancers' exit ends the first reel.

|

| Fredi Washington |

Insert closeup of the wispily-clad Fredi Washington in her dressing room, obviously ill, but under the spell cast by the music. The whiteness of her complexion is reemphasized by her white flapper costume, a counterweight to the dark, male images that punctuate and finally (at the melodramatic climax) supersede the artificial, revue-style performance structure of the scene. A slow pan across the front row of the orchestra lingers on Duke's placid face: Fredi's desire.

Suddenly, Fredi's point of view goes into a spin, and the stage show becomes a swirling kaleidoscope of blacks, whites, and greys, repeating the two dance routines by the quintet in a log shot through a rotating prism that fractures the screen image into a black and tan fantasia of rhythmic motion. Standish D. Lawder calls our attention to these same fracturing techniques in Dudley Murphy's cinematography for Ballet Mecanique in 1924. The opening shot of the silent film's second sequence revealed

... an arrangement of highly reflective Christmas tree ornaments against a background of geometric elements. Through prismatic fracturing, their number is multiplied on the screen and, when set in motion, the elements of this truly Cubist composition move about in syncopated rhythm as if linked together by invisible tie-rods... The importance Leger placed on the device of the prism is signaled by his note of thanks: "An important contribution due to a technical novelty of Mr. Murphy and Mr. Ezra Pound-- the multiple transformation of the projected image." (10)

An identical effect, sustained to the very limit of the spectator's endurance, obtains here in the black and tan whirligig. Again, as in Leger's masterpiece, time, space, and the identity of the screen image are subordinated to the demands of a "ballet mecanique." When, moreover, in Black and Tan visual rhythm is again subordinated to music, we begin to approximate the syntax delineated by Altman in his paradigm for the film musical genre, the abandonment of the representational mode and "the reversal of the traditional image/ sound hierarchy" for which the top-shot kaleidoscope images of Busby Berkeley serve as prototypes:

Constituting the locus classicus of the musical's tendency to subordinate image to sound, Berkeley's films have too often been treated as eccentric and atypical. Though their technique may be extreme, the general patterns they establish are representative, indeed symbolic of the musical's most fundamental configurations. (11)

How delightfully unexpected it is to discover the semantic origins of Berkeley's style in the Cubist experiments with film form nearly a decade earlier! Yet their syntactic placement in the show sequence of Black and Tan makes such a connection hard to ignore.

Finally, the emcee arrives to introduce Fredi. He appears to be a white man, unidentified in the credits, but suggestive of Irving Mills himself. He announces to the audience, "You all know our star has been sick for quite some time," but he assures us that she is "better now." With "the inimitable Fredi Washington" the band goes uptempo into the "Tiger Rag"-ish "Cotton Club Stomp>" For her frantic shimmy, rendered in alternating long and medium shots, the point of view is put back into the audience, except for one impossible view from below the mirrored floor, again anticipating a Busby Berkeley "flower" shot from above. In an important reversal of later generic conventions (but quite typically for the lachrymose 1920s film musical) she manages to dance into the paroxysms of a heart attack and collapses, a white-on-white heap on a dark floor.

"Get her out of here, boys!" cries the honcho emcee. "Keep the show on!" The name of the actor is not given in the film nor in any other source I have been able to find. More significantly, his racial identity is not quite clear from the lighting of his scenes. In a film conceived around the themes of black and white, could it be coincidental that Fredi's boss is a grey?

Black flunkies remove Fredi's limp form. Duke carries on nobly as a jungle-garbed female chorus line performs a jiggly sex dance to "Flaming Youth," until one of the emcee's "boys" breaks ranks and has a hurried conversation with him. "Don't tell him now," the emcee yanks him into the shadowy wings.

*

A highly stylized, expressionistic miss en scene displaces what earlier had been the "realistic" setting of Ellington's flat. The image reappears, a glaring shadow fantasy of human forms projected as a backdrop. The camera tilts down to the Hall Johnson Choir singing the last, plaintive strains of the spiritual "Same Train," the souls of black folk offering solace in the face of the incomprehensible white world. They are followed by a closeup of Fredi, who languishes at the edge of life, Ellington's piano at her bedside: "Duke, play me the 'Black and Tan Fantasy'."

A jazz explosion ensues, with the choir joining in, a "jungle blood" synthesis of sacred and profane imagery. The shadow screen re-erupts in a swaying ballet of upraised hands and uplifted horns as preacher Ellington calls and the faithful moan in response. The blues choruses proceed in long shot: Whetsol's trumpet, "Tricky Sam" Nanton's trombone, and Barney Bigard's wailing clarinet.

The choir rides Whetsol's final, climactic trumpet passage to the famous Chopin death-march tag, during which the fatal glance is exchanged for the last time: Duke Ellington a study in gray, and then the agony of Fredi Washington, closing her eyes in death on the final note. Logically, this should be the last shot, but after she has died, her last, blurred image of Ellington resurrects itself into the film's final fade.

The metaphoric blur at the end of the film hypothesizes a mystery: the Ellington mystique that would sustain him for the length of his career, stretching almost a half-century ahead. By the 1930s, the "race" label would be dropped from Ellington's recordings. His appearances and participation in films would be extensive, ranging from band shorts, art films, appearances in Hollywood feature productions, full length scores (Anatomy of a Murder, 1959, and Paris Blues, 1961) to the magnificent documentaries of his later years. Nowhere, however, would he again play a leading man in a narrative film; indeed; it would be many years before any black actor would play such a role in a major-studio movie. Before the post-World War Two race cycle in Hollywood, Ellington was a Negro "first," here as in so many other respects.

The marvel is that Black and Tan dared to break so many Hollywood taboos, never quite managing to resolve its social theme in the tidy manner perfected in the Hollywood musical's glory years. In the history of film it remains, however unheralded, an attractive experiment-- in sight, sound, and theme -- that continues to merit our interest.

NOTES:

1. R. D. Darrell, 156.

2. Barry Ulanov, 56.

3. Irving Mills, 6.

4. Harold Cruse, 109.

5. Benny Aasland, 1983.

6. Klaus Stratemann, 1983.

7. Donald Bogle, 150-153.

8. Leroy Ostransky, 182.

9. Jim Haskins, 29 ff.

10. Standish D. Lawder, 137.

11. Rick Altman, 73.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aasland, Benny. DEMS Bulletin no. 2, 1983.

Altman, Rick. The American Film Musical. Bloomington IN: Indiana U, 1987.

Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks. New York: Bantam, 1974.

Cruse, Harold. The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. New York: Morrow, 1967.

Darrell, R. D. "Black Beauty," disques. (Philadelphia: H. Rover Smith), June 1932, 152-161.

Haskins, Jim. The Cotton Club. New York: Random House, 1977.

Hirschhorn, Clive. The Hollywood Musical. New York: Crown, 1981.

Lawder, Standish D. The Cubist Cinema. New York: NYU, 1975.

Mills, Irving. "I Split with Duke When Music Began Sidetracking," Down Beat, November 5, 1952, 6.

Stratemann, Klaus. DEMS Bulletin no. 3, 1983.

Ulanov, Barry. Duke Ellington. New York: Creative Age, 1946.

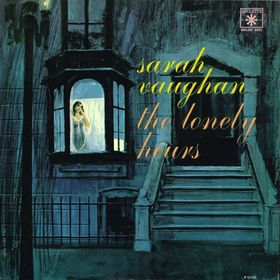

- The Lonely Hours,(Roulette, 1962)

Sarah Vaughan's Roulette recordings exhibit some of her best vocal work, and this one is no exception. Her accompaniments here range from small jazz combos to a large string orchestra and a big band whose arrangements were created by Benny Carter, although the band personnel is not given in Leslie Gourse's notes.

As the album's title implies, the selections consist mostly of ballads, but there is nothing draggy or static here. "I'll Never Be the Same" is performed as a full-throated exercise at a medium tempo, while "If I Had You" is taken at an easy, relaxed swing. "You're Driving Me Crazy" gets an unusual, soft reading that suggests Sass is serious, not joking around as in most renditions. The crown jewel in this collection (although there are many contenders) is probably "Solitude," which somehow evokes the vocalists on Ellington's version from the mid-1940s, and even its first recording with Ivie Anderson the previous decade.

As the album's title implies, the selections consist mostly of ballads, but there is nothing draggy or static here. "I'll Never Be the Same" is performed as a full-throated exercise at a medium tempo, while "If I Had You" is taken at an easy, relaxed swing. "You're Driving Me Crazy" gets an unusual, soft reading that suggests Sass is serious, not joking around as in most renditions. The crown jewel in this collection (although there are many contenders) is probably "Solitude," which somehow evokes the vocalists on Ellington's version from the mid-1940s, and even its first recording with Ivie Anderson the previous decade.

- The Explosive Side of Sarah Vaughan, (Roulette, 1963)

Again, the album's contents are indicated by its title: mid-tempo bounce tunes alternate with uptempo flag-wavers. Sometimes a single track runs the gamut between the two, as in "Falling in Love with Love," which begins as a slow, laid-back ballad and accelerating to double-time in the third chorus.

Beyond any doubt, Orange Crate Art is the single best release of 1995. As one would expect, Van Dyke Parks's instrumental arrangements are lush or, but Brian Wilson's multitracked vocals, arranged by himself, are some of the best of his later career. (Why did Parks enlist Wilson for the vocals? "Because I can't stand the sound of my own voice," he once explained.) All of the tracks are little marvels, from the opening title track through the instrumental "Lullaby" by George Gershwin, but my favorites are the loping-along Western epic "San Francisco" and the nostalgic "Turn Back Time," which manages to do just that with a magnificent harmonic shift in its chorus. The majority of the songs celebrate the same California settings that are depicted in the package's artwork.

- Laura Nyro and Labelle, Gonna Take a Miracle (Columbia, 1971)

This disc is a lovely bit of nostalgia for the soul classics of the early '60s, before the genre acquired the glitz and glamor piled upon it later in the decade. The menu partakes of a bit of everything, from Phil Spector's girl groups to early Motown hits by The Miracles, the Holland–Dozier–Holland songwriting team, and Marvin Gaye, from "You Really Got a Hold on Me" to "Spanish Harlem." Nyro meshes perfectly with the three-woman team Labelle singing backup. Gamble and Huff, the architects of the "Philadelphia Sound" in the 1970s, appear to be the arrangers of the backing tracks, while Laura and Patti & Co., I believe, worked out the vocal parts. (Nyro probably contributed her talents on piano as well.) The CD reissue also includes four bonus tracks, live performances by Laura Nyro.

- Count Basie, The Count Basie Story (Properbox 4-CD, 1936-1950)

Proper Records has done a proper job compiling this overview of Count Basie's early years, from the earliest, almost clandestine, sextet recordings by "Jones-Smith Inc." to the octet recordings at the time Basie was compelled to break up his big band of the 1940s.

The set focuses exclusively on the Count's "Old Testament" band. Unlike the 3-CD Decca recordings set, it presents no alternate takes, so there is a lot of room to explore these, as well as the succeeding Columbia and Victor sides of the 1940s. Overall, the sound quality of the set is decent, if not spectacular, but the range of the material renders it well worth hearing. Throughout there is the band's magnificent rhythm section with Basie on piano, guitarist Freddie Green, bassist Walter Page, and master percussionist Jo Jones.

|

| Treasured autograph, ca. 1980 |

Basie's piano parts are minimalist: he never pushes the tempo, preferring instead to establish a relaxed groove into which the rest of the band falls. Starting with Lester Young ("Shoe Shine Boy," "Roseland Shuffle," "Lester Leaps In," "Taxi War Dance"), one of the great pleasures here is to catch the succession of great tenor sax soloists, including Herschel Evans ("Blue and Sentimental," "One O'Clock Jump"), Buddy Tate ("Rock-a-Bye Basie"), Don Byas ("Harvard Blues," "Royal Garden Blues," "Sugar Blues"), Lucky Thompson ("Avenue C"), Illinois Jacquet ("Rambo," "The King"), and Paul Gonsalves ("Bill's Mill," Swinging' the Blues"). Also on hand for long stretches are trumpeters Harry "Sweets" Edison and Buck Clayton, and master trombonist Dicky Wells. The great vocalists Jimmy Rushing and Helen Humes are also given ample exposure.

The set also provides extensive liner notes by reissue producer Joop Visser.

- Freddie Hubbard, Open Sesame (Blue Note, 1960)

Bright, crackling Freddie Hubbard is here just beginning his recording career among some very fast company. Tina Brooks, in particular, is a completely assured soloist and the composer of two of these tracks (Hubbard would return the favor six days later by appearing on Brooks's release True Blue (see below). The outstanding selection here is Brooks's "Gypsy Blue," a lovely, lilting theme that resembles the work on his own album.

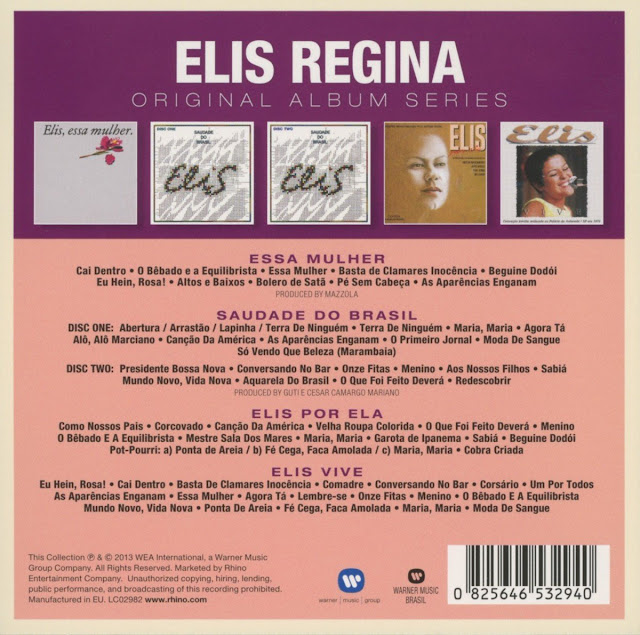

- Elis Regina, Original Album Series (Warner Bros./ Rhino, 1979-1980)

Elis Regina recorded some of her most brilliant work for the Warner Bros. label late in her career, with arranger/ bandleader (and husband) César Camargo Mariano in accompaniment. The acme of the set is Saudades do Brasil, a two-disc studio performance of her magnificent 1980 touring show. But the remainder is not far behind.

My only complaint is that, instead of including her stunning 1979 Montreux concert recording , the set's producers decided to include a single-disc compilation, Elis por Ela, which includes a few tracks of Montreux material, but is otherwise a redundancy.

My only complaint is that, instead of including her stunning 1979 Montreux concert recording , the set's producers decided to include a single-disc compilation, Elis por Ela, which includes a few tracks of Montreux material, but is otherwise a redundancy.

OUR CAR CLUB

A recent addition to my mobile listening, True Blue, sadly, was the only Tina Brooks album issued during his lifetime. His was a unique sound on the tenor sax, well worth hearing on his own recordings and those he made as a sideman, for Jackie McLean, Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Smith, and others.

- Tina Brooks, True Blue (Blue Note, 1960)

A recent addition to my mobile listening, True Blue, sadly, was the only Tina Brooks album issued during his lifetime. His was a unique sound on the tenor sax, well worth hearing on his own recordings and those he made as a sideman, for Jackie McLean, Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Smith, and others.

- Duke Ellington, Duke 56 - 62, vol.2. (Columbia [France]; released 1984)

I first heard this set, a double-LP compilation, back in the day. By the late Don Miller's kindness, I managed to make myself a cassette copy; unfortunately, I then had the tendency to ramp up the gain on my cassette deck.. Horrible distortion.

A few years ago, I had the good fortune of spotting a sale of the complete set of Ellington, 56 - 62, all three volumes. The price was right, and I continue to listen to this set, one part of it or another. Not bad for a needle-drop burn to digital.

This time it was Volume 2. There are lots of attractive tracks, mostly stuff unissued on LPs, single-only releases and alternate mono or stereo versions. The material itself includes two versions of "Jingle Bells," "Track 360," trio versions of "All the Things You Are," and Billy Strayhorn's "Pomegranate" (an unissued sliver from A Drum Is a Woman. ) The main attraction for me has always been the various treatments accorded Duke's theme for The Asphalt Jungle television series in 1961. (One of them reveals Paul Gonsalves champing at the bit, bolting out of the starting gate ahead of the band.) Nice arrangements, too, especially on the two versions on Disc 2. You can dance to it, so I'd give it about a 98.

- Abbey Lincoln, Through the Years, Disc 3 (Verve, 1956 - 2007)

|

| A TRUE APOSTLE OF BLACK WOMANHOOD |

This 3-disc compilation immediately led me to buy everything I could find by dear Abbey.

As the set demonstrates, she had more than one persona. Disc 1 begins with performances from the late 1950s as a sex kitten in a Hollywood gown (as shown on the sleeve of her earliest recording). In her second incarnation, from the end of the '50s into the '60s, Abbey was married to Max Roach, who (along with his great contemporaries), gave Abbey the opportunity to expand her vocal limits (Thelonious Monk taught her not to be "too perfect.") In addition to recording on her husband's projects, Abbey began performing-- and writing-- under her own name, on jazz labels Riverside and Candid.

The 1970s and '80s seem to have been a time for reflection and refinement of her altogether unique style. Her recordings were then scattered among several labels, but beginning in 1990 she began a long residence on the Verve label, a very fruitful one that showed how much she had learned over more than thirty years as a singer. Discs 2 and 3 cover the Verve releases exclusively.

The disc I carry around is from this latter part of her career. Abbey's last recording came out in 2007; she died in 2010.

As the set demonstrates, she had more than one persona. Disc 1 begins with performances from the late 1950s as a sex kitten in a Hollywood gown (as shown on the sleeve of her earliest recording). In her second incarnation, from the end of the '50s into the '60s, Abbey was married to Max Roach, who (along with his great contemporaries), gave Abbey the opportunity to expand her vocal limits (Thelonious Monk taught her not to be "too perfect.") In addition to recording on her husband's projects, Abbey began performing-- and writing-- under her own name, on jazz labels Riverside and Candid.

The 1970s and '80s seem to have been a time for reflection and refinement of her altogether unique style. Her recordings were then scattered among several labels, but beginning in 1990 she began a long residence on the Verve label, a very fruitful one that showed how much she had learned over more than thirty years as a singer. Discs 2 and 3 cover the Verve releases exclusively.

The disc I carry around is from this latter part of her career. Abbey's last recording came out in 2007; she died in 2010.

NEXT: Chicago's Blue Note