NOTE: An unpublished ms submitted to Prof. Sorenson, Fall 1987. Perusing it now, what with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent War on Terror, it seems particularly apt as a contemporary critique. The fanciful title must have been suggested by some good weed.

THE HERMENEUTIC HEURETICS OF CONRAD'S SECRET AGENT

In principle what one of us may or may not know as to any given fact can't be a matter for inquiry to the others. --The Professor (Chapter 4)

A bit of newspaper with a few lines of print on the suicide of a nameless woman twists its way through the gusting dust and debris of a desolate Soho street: "An impenetrable mystery seems destined to hang over this act of madness and despair." (Chapter 13) A week earlier, while the headlines shrieked at every street corner of a powerful explosion in Greenwich Park, two men, a "Doctor" and a "Professor,"getting drunk within the din of the Silenus, likewise had to admit "some mystery" amid the debris: a charred hole at the root of a tree, a man's body blown to pieces. "The rest's mere newspaper gup," one of them says.

These men are distinguished from the average gup-consumer by the fact that they are intellectuals; they believe they know something others don't. One of them, in fact, had provided the chemical device for the explosion, while the other was the erstwhile comrade of the man who plotted its detonation. They think of themselves, moreover, as active participants-- agents-- in the historical flow, unlike the faceless crowd:

... the mass of mankind mighty in its numbers... numerous like locusts, industrious like ants, thoughtless like a natural force, pushing on blind and orderly and absorbed, impervious to sentiment, to logic, to terror, too, perhaps. (Chapter 5)

This mass of mankind sustains itself on mass-media "treacle," and it is most often seen milling about street-corner ideology troughs, the news vendors. As it happens the two intellectuals are continuing a debate, posed a month ago, which they will attempt to settle at a third meeting ten days from now. The subject of their discussion, the central issue of the novel, is precisely the efficacy of propaganda-- more properly, of Science-- upon human history.

The terms of the argument cover the gamut of radical theory. At one extreme lies the non-consequent, passive historical determinism of the "ticket-of-leave apostle" and former apprentice locksmith, Michaelis, who views humanity as the object of the material world:

History is made by men, but they do not make it in their heads. The ideas that are born in their consciousness play an insignificant part in the march of events. (Chapter 3)

At the opposite pole stands the anarchist Professor, a student chemist and a pathetic, a human bomb whose cosmos consists exclusively of his own, self-obsessed subject. (The "old terrorist" Karl Yundt holds a similar position, but lacks the "force" to undergo the refinement of such an utter break with the human race.) Finally, somewhere near the apex of the argument, the Doctor, a failed medico, imagines a synthesis between the subjective and objective factors of history.

Lately the news has been full of an International Conference on terrorism to be held in Milan. This is to be a great tribunal of public opinion, the fulcrum for the actions of secret agents, including the nominal Agent Delta, alias "Mr. Verloc," who mutters that he is "in the habit of reading the daily papers" and even fancies that he understands what he reads. Yet his superior-- and nemesis-- Mr. Vladimir contemplates an act "of destructive ferocity as to be incomprehensible, inexplicable, almost unthinkable as a lever to rally corpulent, bourgeois, "natural-born British subjects," the very likenesses of Mr. Verloc himself, to the defense of European Civilization.

The text most of these characters inhabit and perceive is black and white, arranged in straight lines, uncomplicated causes and predetermined effects. Grey, however, is an ominous uncertainty, a lack of clarity, a chimera. Mr. Vladimir regards from his disdainful distance "a grey sheet of printed matter" with its "F.P." logo and crude hammer-pen-torch imagery. "A charabia every bit as incomprehensible as Chinese," he sneers. "Isn't your society capable of anything else but printing this prophetic bosh in blunt type on this filthy paper?" (Chapter 2)

The society "F.P." to which he refers is the Future of the Proletariat, of which Mr. Verloc is vice-president and whose grey propaganda rag is edited by the same Doctor who will presently be arguing a point of political theory with the Professor, over a red-and-white tablecloth at the Silenus. To the Professor, the laws of history are motivated not by propaganda, but by another sort of "F.P." altogether: the Force of Personality. Curiously, neither of them appears to think remarkable a certain pink hue in the pages of the daily newspaper lying open in front of them both; in a world perceived in cool blacks, whites, and grey, only the trashy mass media appear to reflect the heat of living events.

The Mystery: a finely-shaded detective story, an essay on epistemology, frames the text of The Secret Agent. Paradoxically, the more the text seems to solve this mystery, the more it appears to lose its grip upon the solution. At one point, text "explodes" in a simultaneous constructing and deconstructing, yet for the most part it is static, talky, and cluttered with everyday peculiarities. On its surface we are allowed to witness only one "extraordinary" event, the anticlimactic murder of "Adolf Verloc," narrated in a strange, matter-of-fact fashion; the rest is perceived through other media: news reports, dialogue, interior monologue, and a certain amount of authorial second-guessing. As a result, we are paradoxically intimate with the Secret of each character, but at the same time distant enough to view all of them as the objective components-- victims, as well as agents-- of a process we are privileged to contemplate at much wider vantage. In effect, we are scientists examining the results of an experiment.

Naturalism in red and shades of grey: The Secret Agent is a social experiment gone awry, for there are really no straight lines here. A multiplicity of parallel correspondences dissolves at the point of infinity into a circle as perfect as a woman's gold wedding ring. There are only circles , from absolutism through capitalism to anarchy and back to absolutism. The social machine generates its own doom, a Secret Agent, who/ which touches off an explosion that cracks the very structure of the text, causing it to redouble violently upon itself.

The most obvious dislocation is the creation of a time warp: the explosion is enacted twice, redoubling its force, in the public scene with the Doctor and Professor and again with Inspector Heat's intrusion into the privacy of the Verloc home. Within each character, shards of memory are jarred loose in flashbacks (e.g., Verloc's in Chapter 2, Heat's in Chapter 5, the Assistant Commissioner's in Chapter 6, etc.). The text flashes in unmistakable parallelisms, systemic repetitions, and reversals of character and scene. Its suborbital systems are unstable, eccentric, endlessly repetitive mirror image within the slivers of text sent flying by the explosion at the root of a Tree at the edge of pastoral eternity, the threshold of of knowledge. Everything and everyone is turned inside-out, base and superstructure, subject and object, police and criminal, yet the text remains within the larger pattern of the fabric of historical reality; nothing is really out of control here.

-- Chief Inspector Heat, Chapter 5

The terms of the argument cover the gamut of radical theory. At one extreme lies the non-consequent, passive historical determinism of the "ticket-of-leave apostle" and former apprentice locksmith, Michaelis, who views humanity as the object of the material world:

History is made by men, but they do not make it in their heads. The ideas that are born in their consciousness play an insignificant part in the march of events. (Chapter 3)

At the opposite pole stands the anarchist Professor, a student chemist and a pathetic, a human bomb whose cosmos consists exclusively of his own, self-obsessed subject. (The "old terrorist" Karl Yundt holds a similar position, but lacks the "force" to undergo the refinement of such an utter break with the human race.) Finally, somewhere near the apex of the argument, the Doctor, a failed medico, imagines a synthesis between the subjective and objective factors of history.

Lately the news has been full of an International Conference on terrorism to be held in Milan. This is to be a great tribunal of public opinion, the fulcrum for the actions of secret agents, including the nominal Agent Delta, alias "Mr. Verloc," who mutters that he is "in the habit of reading the daily papers" and even fancies that he understands what he reads. Yet his superior-- and nemesis-- Mr. Vladimir contemplates an act "of destructive ferocity as to be incomprehensible, inexplicable, almost unthinkable as a lever to rally corpulent, bourgeois, "natural-born British subjects," the very likenesses of Mr. Verloc himself, to the defense of European Civilization.

The text most of these characters inhabit and perceive is black and white, arranged in straight lines, uncomplicated causes and predetermined effects. Grey, however, is an ominous uncertainty, a lack of clarity, a chimera. Mr. Vladimir regards from his disdainful distance "a grey sheet of printed matter" with its "F.P." logo and crude hammer-pen-torch imagery. "A charabia every bit as incomprehensible as Chinese," he sneers. "Isn't your society capable of anything else but printing this prophetic bosh in blunt type on this filthy paper?" (Chapter 2)

The society "F.P." to which he refers is the Future of the Proletariat, of which Mr. Verloc is vice-president and whose grey propaganda rag is edited by the same Doctor who will presently be arguing a point of political theory with the Professor, over a red-and-white tablecloth at the Silenus. To the Professor, the laws of history are motivated not by propaganda, but by another sort of "F.P." altogether: the Force of Personality. Curiously, neither of them appears to think remarkable a certain pink hue in the pages of the daily newspaper lying open in front of them both; in a world perceived in cool blacks, whites, and grey, only the trashy mass media appear to reflect the heat of living events.

The Mystery: a finely-shaded detective story, an essay on epistemology, frames the text of The Secret Agent. Paradoxically, the more the text seems to solve this mystery, the more it appears to lose its grip upon the solution. At one point, text "explodes" in a simultaneous constructing and deconstructing, yet for the most part it is static, talky, and cluttered with everyday peculiarities. On its surface we are allowed to witness only one "extraordinary" event, the anticlimactic murder of "Adolf Verloc," narrated in a strange, matter-of-fact fashion; the rest is perceived through other media: news reports, dialogue, interior monologue, and a certain amount of authorial second-guessing. As a result, we are paradoxically intimate with the Secret of each character, but at the same time distant enough to view all of them as the objective components-- victims, as well as agents-- of a process we are privileged to contemplate at much wider vantage. In effect, we are scientists examining the results of an experiment.

Naturalism in red and shades of grey: The Secret Agent is a social experiment gone awry, for there are really no straight lines here. A multiplicity of parallel correspondences dissolves at the point of infinity into a circle as perfect as a woman's gold wedding ring. There are only circles , from absolutism through capitalism to anarchy and back to absolutism. The social machine generates its own doom, a Secret Agent, who/ which touches off an explosion that cracks the very structure of the text, causing it to redouble violently upon itself.

The most obvious dislocation is the creation of a time warp: the explosion is enacted twice, redoubling its force, in the public scene with the Doctor and Professor and again with Inspector Heat's intrusion into the privacy of the Verloc home. Within each character, shards of memory are jarred loose in flashbacks (e.g., Verloc's in Chapter 2, Heat's in Chapter 5, the Assistant Commissioner's in Chapter 6, etc.). The text flashes in unmistakable parallelisms, systemic repetitions, and reversals of character and scene. Its suborbital systems are unstable, eccentric, endlessly repetitive mirror image within the slivers of text sent flying by the explosion at the root of a Tree at the edge of pastoral eternity, the threshold of of knowledge. Everything and everyone is turned inside-out, base and superstructure, subject and object, police and criminal, yet the text remains within the larger pattern of the fabric of historical reality; nothing is really out of control here.

Alfred Hitchcock's Sabotage, a retitling of Conrad's novel

"... The mind and the instincts of burglar are of the same kind as the mind and the instincts of a police officer... Products of the same machine, one classed as useful and the other as noxious, they take the machine for granted in different ways, but with a seriousness essentially the same.

-- Chief Inspector Heat, Chapter 5

The Machine of the Secret Agent is a mechanistic world of cogs and wheels spinning inexorably toward a shattering explosion. It is a universe of tinny player pianos, purring gas jets, ticking clocks, carving knives set carelessly upon kitchen tables, bells jangling over shop doors, and whirling galaxies refracted through the lens of the Greenwich Observatory. Its inhabitants are secret agents and secret police simultaneously, taking blind stabs into the mystery of history; they both cause and react to the movement of their cosmos, but their observations of events are bizarrely distorted, refracted through the lens of personality. While they sometimes perceive intimations of the Machine's heuristic depths, its fundamental truths, they do so only sporadically, at odd moments, unwillingly. We see this in Mr. Vladimir's pungent remark, "Unhappy Europe! Thou shalt perish by the moral insanity of thy children." Of a fateful back-alley encounter between the Professor and Chief Inspector Heat, the narrating voice insists, "It was in reality a chance meeting." Later on, in a universe where nothing-- and thereby everything-- is left to chance, Inspector Heat grimaces sardonically at the vagaries of fate as a bit of charred cloth conceals itself within his mind. Again and again, the ritual of recognition is enacted and effaced.

Life..., in this connection, is a historical fact surrounded by all sorts of restraints and considerations, a complex organized fact open to attack at every point; whereas I depend on death, which knows no restraint and cannot be attacked. My superiority is evident.

Life..., in this connection, is a historical fact surrounded by all sorts of restraints and considerations, a complex organized fact open to attack at every point; whereas I depend on death, which knows no restraint and cannot be attacked. My superiority is evident.

--The Professor, Chapter 4

From our "readerly" vantage beyond the rim of the hermeneutic circle, within which all points of view are transparent, we behold the Professor's "superiority" as the reverse image of his sense of physical and social inferiority. Unaware of his own inner psychological pinball, he is nonetheless a shrewd "outside" observer oppressed and revolted by the crush of humanity. Prophet of "the perfect detonator," thumb on his ill-concealed pneumatic squeeze-bulb, the Professor is indeed a padlocked pantry of explosives in an anonymous one-room flat.

The source of his power, he realizes, is that his psychopathology is completely open to the guardians of law and order, for his is the philosophically pure anarchism of the raging id. A déclassé intellectual, the "mad dog" spawn of Western Civilization, the Professor posits the Force of Personality to explode the façade of conventional morality, order, and rationality. He anticipates happily the day when citizens will be shot on the street in an open police state. He is the Hammer of our hermeneutic.

The Professor's functional counterpart is Mr. Vladimir, the renegade aristocrat, who primes the entire narrative sequence leading to the social explosion. He is linked to the Professor in the causal chain, but only indirectly, as by a mysterious black box: Agent Delta (not the sort of detonator he had in mind). Mr. Vladimir, too, is the victim of paranoid delusions of grandeur:

Descended from generations victimized by the instruments of an arbitrary power, he was racially, nationally, and individually afraid of the police. It was an inherited weakness, altogether independent of his judgment, of his reason, of his experience. He was born to it. But that sentiment... did not stand in the way of his immense contempt for the English police. (Chapter 10)

The source of his power, he realizes, is that his psychopathology is completely open to the guardians of law and order, for his is the philosophically pure anarchism of the raging id. A déclassé intellectual, the "mad dog" spawn of Western Civilization, the Professor posits the Force of Personality to explode the façade of conventional morality, order, and rationality. He anticipates happily the day when citizens will be shot on the street in an open police state. He is the Hammer of our hermeneutic.

The Professor's functional counterpart is Mr. Vladimir, the renegade aristocrat, who primes the entire narrative sequence leading to the social explosion. He is linked to the Professor in the causal chain, but only indirectly, as by a mysterious black box: Agent Delta (not the sort of detonator he had in mind). Mr. Vladimir, too, is the victim of paranoid delusions of grandeur:

Descended from generations victimized by the instruments of an arbitrary power, he was racially, nationally, and individually afraid of the police. It was an inherited weakness, altogether independent of his judgment, of his reason, of his experience. He was born to it. But that sentiment... did not stand in the way of his immense contempt for the English police. (Chapter 10)

Two-faced Mr. Vladimir is truly a split personality (a "Hyperborean swine... what you might call a gentleman"); a clean-shaven "dogfish... a noxious, rascally-looking, altogether detestable beast"). His public charm at the Great Lady's salon conceals the vile heart that beats within his inner chamber at the embassy. Confessing his secret loathing of the nation and class whose hospitality sustains him, Mr. Vladimir nevertheless takes it upon himself to act as their historical proxy by plotting an attack on rationality itself, by exploding the bourgeois belief in the democratic sacred cow of Science. He, like the Professor at the other end of the social spectrum, is that stranger in our midst, the savage end-product of civilization.

Nothing that happened to [Michaelis] individually had any importance. He was like those saintly men whose personality is lost in the contemplation of their faith. His ideas were not in the nature of convictions. They were inaccessible to reasoning. (Chapter 6)

The role opposite the Hammer is played by patient (in both senses) Michaelis, the author cum celebrity cum hermit. The Pen in our equation, he is ironically unable to write the language of "consecutive thought." His utopian idealism ("Capitalism has made socialism, and [its laws] are responsible for anarchism... Then why indulge in prophetic phantasies?") renders itself precisely into a "prophetic fantasy," an act of pure contemplation, because it lacks a Subject, a conscious historical agency.

At the beginning of his political career, the locksmith's arrest produced a bunch of skeleton keys, a heavy chisel, and a short crowbar (but no hammer!) The "ticket-of-leave" apostle remains the perpetual prisoner of innocence, a still, small voice from the country wilderness. As a disconnected superego, he occupies a small upstairs room above the orphan Stevie on the morning of the explosion, an ironic counterpart to the brutal "lost" father.

Stevie, still an ego in formation, becomes the Torch in the F.P. hermeneutic. The departure of Mother to the invalid home leaves him with surrogate parents, the Verlocs. "Poor Stevie" is left alone to solve the mystery of the cosmos with pencil and paper in "coruscations of innumerable circles suggesting chaos and eternity" on Mother's kitchen table (down two steps from the cozy parlor walled off from the sleazy shop opening onto the mysterious world of the street.) Within the Verloc family, life poses no mystery at all; there is "good," there is "poor," and there is "beastly," as long as he can keep these categories distinct and pristine in his mind, Stevie can be at peace within himself. Outside the circle of the family, however, the identity "Stevie" does not exist: to all but Winnie, he is a mere cipher, a fair-haired lad, a degenerate, a smoldering address label among scattered bits of flesh and bone. At the textual center of The Secret Agent the Verloc family self-destructs in the successive disappearances of "Stevie," "Winnie," and "Adolf."

From a certain point of view we are here in the presence of a domestic drama.

At the beginning of his political career, the locksmith's arrest produced a bunch of skeleton keys, a heavy chisel, and a short crowbar (but no hammer!) The "ticket-of-leave" apostle remains the perpetual prisoner of innocence, a still, small voice from the country wilderness. As a disconnected superego, he occupies a small upstairs room above the orphan Stevie on the morning of the explosion, an ironic counterpart to the brutal "lost" father.

Stevie, still an ego in formation, becomes the Torch in the F.P. hermeneutic. The departure of Mother to the invalid home leaves him with surrogate parents, the Verlocs. "Poor Stevie" is left alone to solve the mystery of the cosmos with pencil and paper in "coruscations of innumerable circles suggesting chaos and eternity" on Mother's kitchen table (down two steps from the cozy parlor walled off from the sleazy shop opening onto the mysterious world of the street.) Within the Verloc family, life poses no mystery at all; there is "good," there is "poor," and there is "beastly," as long as he can keep these categories distinct and pristine in his mind, Stevie can be at peace within himself. Outside the circle of the family, however, the identity "Stevie" does not exist: to all but Winnie, he is a mere cipher, a fair-haired lad, a degenerate, a smoldering address label among scattered bits of flesh and bone. At the textual center of The Secret Agent the Verloc family self-destructs in the successive disappearances of "Stevie," "Winnie," and "Adolf."

From a certain point of view we are here in the presence of a domestic drama.

-- Assistant Commissioner (Chapter 10)

"Stevie," as we have seen, is exploded into space: "No. 32 Brett Street." Further along in the familial chain-reaction, "Winnie" explodes into time, transformed into the anonymous anniversary date, "24 June, 1879" inscribed within her wedding ring. The central presence of ersatz Agent Delta, however, expires in stages: "Adolf" ceases to exist as his blood spatters upon the floor beneath his parlor sofa. "Mr. Verloc" goes next: his bank account, the only thing that matters about him in the end, belongs to the fictional "Mr. Prozor." The remaining corpse therefore bears no "real" identity. "Agent Delta" must, for diplomatic reasons, remain an "open secret" between the House of Lords and a certain embassy.

Preventor/ detonator Secret Agent Delta (orthographically an upside-down V, a counter to himself and to Mr. Vladimir; in chemical formulae, the symbol of Heat as the catalyst in a reaction) is the most conventional bourgeois gentleman, the corpulent Mr. Verloc. Mr. Vladimir is constitutionally compelled to humiliate such a man. In turn, we witness the agony of "Adolf," whose oppressive days and fevered nights are lived in a necessary and inevitable obsession with his alter-ego, the face of whom appears in the very conjugal window of his soul. This absence of identity is the Force Of Personality with a vengeance, for "Adolf" emerges, after all, as the "perfect detonator."

Identities are not stable entities within the historical dialectic of the text. They are deceptive, sardonic subterfuges ("Professor," "Doctor"), generic or honorific titles of function ("Great Lady," "Assistant Commissioner"), formal sobriquets of relationship ("Mother," Comrade Ossipon"), and terms of endearment and / or entreaty ("Tom," Adolf). Finally, there is the problematic identity of "Joseph Conrad," who wishes to call attention to this whole sticky business of names.

All the novel's positive values-- decency, culture, stability, humanism-- lie with the Old Regime of "the empire on which the sun never sets," the order personified by the Great Lady (who champions the ruined ex-convict Michaelis) and Sir Ethelred, the "Great Personage" who sponsors the nationalization of fisheries in the House of Lords "("the house par excellence, in the minds of many millions of men"). The gentry appear here as historical anachronisms. There is "Toodles," Sir Ethelred's innocent squire (unpaid) who imagines his own identity as something which can endure "unchanged," and who, upon the whole believes this earth to be "a nice place to live on." Sir Ethelred himself, the political counter to Mr. Vladimir, perceives himself a mover and shaker of the empire. Yet he directs his efforts at "sprat" (of the herring family, the red variety), instead of "dogfish." He does not wish to be bothered with details. The Great Lady likewise is content to view the "surface currents" of social life, the sort who swim through her salon. None of them care to risk their bearings in unplumbed depths. The shattering penalty to be exacted upon the perfidious Vladimir, after all, shall be the suspension of his honorary membership privileges at the Explorers Club. "They'll have to get a hard rap over the knuckles over this affair," Sir Ethelred proclaims.

The character most interested in getting to the bottom of this fathomless business is the nameless Assistant Commissioner. A former colonial officer of the same empire, he prefers the well-drawn boundaries (white and black) between civilization and heathen insurrection to the endless stream of bureaucratic intrigue and paperwork of the bourgeois metropolis. His relationship with Annie, his own "domestic drama," provides the secret impetus for his entry into the affair of the Secret Agent. From the outset, he pursues the mystery, apparently disinterested, with "excellent hopes of getting behind it and finding there something else than individual freak of fanaticism." In the end, however, he is forced to report, "What I mainly came upon was a psychological state," rather than the "logical" plot he had set out to find. In the meantime, the "truth" of Agent Delta's secret confession is slipping into time and out of history.

"You revolutionists... are the slaves of social convention, which is afraid of you; slaves of it as much as the very police that stands up in the defense of that convention. Clearly you are, since you want to revolutionize it." --The Professor (Chapter 4)

The final chapter concludes the debate between the Doctor and Professor, and the Force Of Personality seems to have the last word, counterposed to the vision of Michaelis of "a world planned out like an immense and nice hospital" governed by the tenets of Faith, Hope, and Charity. The Doctor, who now knows the scoundrel within his skin, is forced to yield to the Professor's prophecy, a world of "madness and despair": "Give me that for a lever, and I'll move the world." Yet in the coda that follows, as they separate to pursue their private demons, the Professor is no more certain of his argument than the humbug Doctor: "He had no future."

We are left with a sort of sociopolitical Heisenberg Principle: certainty dissolves, and the historical subject remains a mystery. The social explosion ends in social paralysis. We remind ourselves of La Belle Epoch and its literary lions, the Edwardian prophets of irony and pessimism in the entr'acte before the Great War, but we must also recall these years as a time of retreat for the international workers' movement with its fierce debates and isolated explosions, particularly in the failed Russian Revolution of 1905. Hindsight permits us to see that event as a dress-rehearsal for the historic drama of 1917, but Conrad, in the last analysis, could not foresee the Future of the Proletariat stretching forward into this century. The terms of his debate are those of Plekhanov and Bakunin, not Lenin or Fidel, who have had a great deal to say about the subjective factor in human history.

It comes as no surprise then that the working class itself appears so seldom in the text. When not part of the passive, undifferentiated mass, workers appear only as greatly stereotyped figures, chiefly the casual (and slightly sinister) contacts made by the idiot Stevie: the anonymous cabman and Mrs. Neale are portrayed as brutalized drudges, petty thieves, and chronic alcoholics. Hence Conrad foresaw only continuous historical stalemate, the futility of class struggle. For him the Future of the Proletariat awaits the initiative of an outside Secret Agent, a historical "accident" to obliterate the present and recreate it endlessly.

"Stevie," as we have seen, is exploded into space: "No. 32 Brett Street." Further along in the familial chain-reaction, "Winnie" explodes into time, transformed into the anonymous anniversary date, "24 June, 1879" inscribed within her wedding ring. The central presence of ersatz Agent Delta, however, expires in stages: "Adolf" ceases to exist as his blood spatters upon the floor beneath his parlor sofa. "Mr. Verloc" goes next: his bank account, the only thing that matters about him in the end, belongs to the fictional "Mr. Prozor." The remaining corpse therefore bears no "real" identity. "Agent Delta" must, for diplomatic reasons, remain an "open secret" between the House of Lords and a certain embassy.

Preventor/ detonator Secret Agent Delta (orthographically an upside-down V, a counter to himself and to Mr. Vladimir; in chemical formulae, the symbol of Heat as the catalyst in a reaction) is the most conventional bourgeois gentleman, the corpulent Mr. Verloc. Mr. Vladimir is constitutionally compelled to humiliate such a man. In turn, we witness the agony of "Adolf," whose oppressive days and fevered nights are lived in a necessary and inevitable obsession with his alter-ego, the face of whom appears in the very conjugal window of his soul. This absence of identity is the Force Of Personality with a vengeance, for "Adolf" emerges, after all, as the "perfect detonator."

Identities are not stable entities within the historical dialectic of the text. They are deceptive, sardonic subterfuges ("Professor," "Doctor"), generic or honorific titles of function ("Great Lady," "Assistant Commissioner"), formal sobriquets of relationship ("Mother," Comrade Ossipon"), and terms of endearment and / or entreaty ("Tom," Adolf). Finally, there is the problematic identity of "Joseph Conrad," who wishes to call attention to this whole sticky business of names.

All the novel's positive values-- decency, culture, stability, humanism-- lie with the Old Regime of "the empire on which the sun never sets," the order personified by the Great Lady (who champions the ruined ex-convict Michaelis) and Sir Ethelred, the "Great Personage" who sponsors the nationalization of fisheries in the House of Lords "("the house par excellence, in the minds of many millions of men"). The gentry appear here as historical anachronisms. There is "Toodles," Sir Ethelred's innocent squire (unpaid) who imagines his own identity as something which can endure "unchanged," and who, upon the whole believes this earth to be "a nice place to live on." Sir Ethelred himself, the political counter to Mr. Vladimir, perceives himself a mover and shaker of the empire. Yet he directs his efforts at "sprat" (of the herring family, the red variety), instead of "dogfish." He does not wish to be bothered with details. The Great Lady likewise is content to view the "surface currents" of social life, the sort who swim through her salon. None of them care to risk their bearings in unplumbed depths. The shattering penalty to be exacted upon the perfidious Vladimir, after all, shall be the suspension of his honorary membership privileges at the Explorers Club. "They'll have to get a hard rap over the knuckles over this affair," Sir Ethelred proclaims.

The character most interested in getting to the bottom of this fathomless business is the nameless Assistant Commissioner. A former colonial officer of the same empire, he prefers the well-drawn boundaries (white and black) between civilization and heathen insurrection to the endless stream of bureaucratic intrigue and paperwork of the bourgeois metropolis. His relationship with Annie, his own "domestic drama," provides the secret impetus for his entry into the affair of the Secret Agent. From the outset, he pursues the mystery, apparently disinterested, with "excellent hopes of getting behind it and finding there something else than individual freak of fanaticism." In the end, however, he is forced to report, "What I mainly came upon was a psychological state," rather than the "logical" plot he had set out to find. In the meantime, the "truth" of Agent Delta's secret confession is slipping into time and out of history.

"You revolutionists... are the slaves of social convention, which is afraid of you; slaves of it as much as the very police that stands up in the defense of that convention. Clearly you are, since you want to revolutionize it." --The Professor (Chapter 4)

The final chapter concludes the debate between the Doctor and Professor, and the Force Of Personality seems to have the last word, counterposed to the vision of Michaelis of "a world planned out like an immense and nice hospital" governed by the tenets of Faith, Hope, and Charity. The Doctor, who now knows the scoundrel within his skin, is forced to yield to the Professor's prophecy, a world of "madness and despair": "Give me that for a lever, and I'll move the world." Yet in the coda that follows, as they separate to pursue their private demons, the Professor is no more certain of his argument than the humbug Doctor: "He had no future."

We are left with a sort of sociopolitical Heisenberg Principle: certainty dissolves, and the historical subject remains a mystery. The social explosion ends in social paralysis. We remind ourselves of La Belle Epoch and its literary lions, the Edwardian prophets of irony and pessimism in the entr'acte before the Great War, but we must also recall these years as a time of retreat for the international workers' movement with its fierce debates and isolated explosions, particularly in the failed Russian Revolution of 1905. Hindsight permits us to see that event as a dress-rehearsal for the historic drama of 1917, but Conrad, in the last analysis, could not foresee the Future of the Proletariat stretching forward into this century. The terms of his debate are those of Plekhanov and Bakunin, not Lenin or Fidel, who have had a great deal to say about the subjective factor in human history.

It comes as no surprise then that the working class itself appears so seldom in the text. When not part of the passive, undifferentiated mass, workers appear only as greatly stereotyped figures, chiefly the casual (and slightly sinister) contacts made by the idiot Stevie: the anonymous cabman and Mrs. Neale are portrayed as brutalized drudges, petty thieves, and chronic alcoholics. Hence Conrad foresaw only continuous historical stalemate, the futility of class struggle. For him the Future of the Proletariat awaits the initiative of an outside Secret Agent, a historical "accident" to obliterate the present and recreate it endlessly.

IN MY ROTATION:

a couple of items from a recent package I received from Hamilton Books/ Music:

- Captain Beefheart, Plastic Factory (GoFaster Records, 1966-73)

The first nine tracks were recorded from a radio broadcast from the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, June 17, 1966. Bonus tracks include broadcasts from various dates and places, from 1967 and 1968 (post- Safe As Milk, pre- Trout Mask Replica). The final track consists of a Beefheart interview with John Peele in the U.K.

Sun Ra, The Early Albums Collection, 1956-1963 (Enlightenment 4-CD box)

Caveats: As usual, there is no session or personnel information. The year of release given here is often at variance with the information given in the Wikipedia entries, and many of Sun Ra's albums released during this period have been omitted. The graphics here sometimes fail to match those that Wiki displays, no doubt because of the many reissues on different labels the albums have undergone.

All that being said, for me this is a worthwhile collection consisting mostly of music I've never heard. More detailed comments appear beside each album included here.

Caveats: As usual, there is no session or personnel information. The year of release given here is often at variance with the information given in the Wikipedia entries, and many of Sun Ra's albums released during this period have been omitted. The graphics here sometimes fail to match those that Wiki displays, no doubt because of the many reissues on different labels the albums have undergone.

All that being said, for me this is a worthwhile collection consisting mostly of music I've never heard. More detailed comments appear beside each album included here.

- Jazz by Sun Ra aka Sun Sound (Sonet, 1956)

- Sound of Joy (Delmark, 1957)

- Super-Sonic Jazz (Saturn, 1957)

- Interstellar Low Ways (Saturn, 1959)

- Jazz in Silhouette (Saturn, 1958)

- The Futuristic Sounds of Sun Ra (Saturn, 1961)

- When Sun Comes Out (Saturn, 1963)

Sun Ra, "Brother from Another Planet"

- The Singles (Saturn/ Evidence compilation, 1955-1960)

- Sun Ra, Strange Celestial Road (Rounder, 1979)

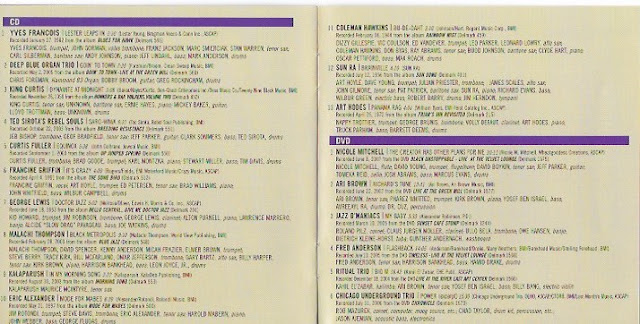

- Various artists, Delmark: 55 Years of Jazz

The track listing below almost says it all. Bob Koester

OUR CAR CLUB

KINKS BONANZA! I replaced some rock items from the ELANTRA COLLECTION with these little masterpieces.

- The Kinks, Face to Face/ Something Else by the Kinks (Pye/ Reprise, 1966, 1967)

- The Kinks, Arthur (Pye/ Reprise, 1969)

NEXT: Blackface Minstrelsy And The Birth Of American Mass Entertainment