Rutgers University Newark, Institute of Jazz Studies, 1986

Author and curator of the Institute, Dan Morgenstern, Martin Williams, one of the world's most admired jazz writers. I don't remember much about Morgenstern's conference presentation, I still remember and agree with his opinion that the music for Anatomy of a Murder was almost too good for the movie.

In 2018 Willard became the first woman to receive the Jazz Journalists Association Lifetime Achievement Award. Beginning as a student based in Washington, she began her association with Duke Ellington in 1949, as his research, educational and public relations counsel, while at the same time working for several other important jazz artists. She was historical consultant to the Duke Ellington Collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and the Library of Congress, the National Endowment for the Arts Music program. She served as consultant also for Martin Williams's and Billy Taylor's Kennedy Center Jazz Series and the National Jazz Service Organization. She was a contributing editor to Down Beat and Jazz and Pop Magazine and a staff writer at JazzTimes. She has annotated more than one hundred recordings, and her articles and photographs have appeared in magazines and journals internationally.

Klause Stratemann's. Duke Ellington: Day by Day and Film by Film was published in 1999.

3. Sjef Hoefsmidt

|

| Benny Aasland |

VI. The 1990s forward

phone call to Joya Sherrill in New York; her own lyrics to "Take the 'A' Train." We agreed that Duke Ellington was "larger than life."

"The Sound of Jazz"

*

A Crooked Thing

A Chronicle of Beggar's Holiday

Oh, love is a crooked thing

And there is nobody can say

All the curious things there are in it

"Brown Penny"

Posterity is as unkind to failures on Broadway as it is elsewhere. No matter what virtues a play or musical may possess, box-office success seems to be the only criterion of whether or not a dramatic work will survive in our memory. For every season's Oklahoma! or My Fair Lady, there are any number of worthies that, for one reason or another, simply didn't catch on with the mass audience. Such was the fate of Beggar's Holiday, the lavish musical comedy of 1946-47 that featured the melodies of Duke Ellington and the lyrics and libretto of John Latouche.

The play opened with great fanfare at the Broadway Theatre in New York the day after Christmas, 1946, and closed some fourteen weeks later, after a disappointing 108 performances. Nevertheless, it was a production of many outstanding qualities, coming as it did in reaction against the optimistic claptrap which soon became the norm among Broadway hits. It boasted a fine cast; it had a distinguished director, a nonpareil set design; and, in the hands of its producers, it had money to burn. In fact, it had all the ingredients of a successful show.

Beggar's Holiday began in the imagination of black producer Perry Watkins, who was the only black member of the local Scenic Designers Union. Watkins had received renown as the designer of the WPA's Negro Theatre Project's first production, Macbeth, at the Lafayette Theatre in 1935, as well as the Federal Theatre's Pinocchio and Guthrie McClintic's production of Mamba's Daughters. Beggar's Holiday, he wrote, "was conceived from the first-- more than a year before it reached Broadway-- as a bi-racial musical."1

Admittedly, featuring black writers and performers and Afro-American themes was not unknown on Broadway in the immediate post-World War II period. The musical Street Scene, with lyrics by Langston Hughes, ran the same season. Other plays with Negro themes included On Whitman Avenue (with Canada Lee) and the Katherine Dunham Company's Bal Negrej. Following the lead of Beggar's Holiday, Finian's Rainbow featured a mixed cast in a portion of the show which satirized Southern-style white supremacism.

This was a Broadway still waltzing through the euphoric dreamland of the Four Freedoms. It was therefore not surprising that someone would come up with the bright idea of showing racial democracy I'm action. All these shows, to one degree or another, were charming exercises in make-believe, perhaps all the more charming because of their naivety. In those days, just having black and white actors occupy the same stage, other than in a servant-master relationship, was an occasion of extraordinary open-mindedness. On the other hand, presenting something as unheard-of as an onstage interracial romance-- as did Beggar's Holiday-- was a gesture in the direction of sophisticated and sincere wishful thinkers.

Beggar's Holiday, however, was different from the other interracial plays in the depth of Perry Watkins's conception. His paramount objective was to make a social and political statement, to prove that a Broadway production could be borne equally by the talents of black and white. "No one realized until opening night," Watkins later wrote, "that it was to become the first completely biracial production in the history of the American theatre... from production staff, authors and orchestrators, stars and supporting cast, singers and dancers, down to the musicians in the pit."2

As such, the show must be viewed as a statement by and for the political left, caught inexorably between the hazy nirvana wartime "unity" and the coming show-business blacklist. In a sense, Beggar's Holiday was the left's last hurrah before the plague years of the 1950s; it is doubtful whether a single participant in the show was not affected to some degree by the red-hunts of that epoch, and several suffered a great deal.

Nevertheless, Beggar's Holiday was not a problem play in the conventional sense, least of all one about race problems. Instead, Watkins envisioned

... a gay satire suggested in modern parallels to the 18th century of John Gay's popular classic, "The Beggar's Opera," and translated into the idiom and tempo of today's America.3

By making it bi-racial, Watkins explained:

... it expressed the integrated cross-sectional spirit of the true American scene... The collaboration is a proof of the universal character of the arts and artists of the theatre. It also shows that democracy works. The harmonious relationships among all concerned and the success of the venture indicate that intelligent Americans regard color as no barrier to artistic cooperation along more general lines for the common good of all Americans.4

With all this in mind, Watkins and co-producer Dale Wasserman first approached John Treville Latouche, a twenty-eight-year-old Virginian who had already established an enviable track record as a lyricist and was still a young, earnest firebrand. In 1935, at the age of eighteen, Latouche had collaborated with composer Earl Robinson on the mordant "Ballad of Uncle Sam," which was conceived as the finale to the WPA revue, Sing for Your Supper. Almost from its beginning one of Paul Robeson's concert pieces, "Ballad of Uncle Sam" achieved sufficient notoriety to come to the attention of right-wingers in Congress who condemned it as evidence of "communist infiltration of the WPA."5

In 1940, Latouche wrote the lyrics to Vernon Duke's score for the stage production of Cabin in the Sky, firmly establishing his credentials as a writer for the musical theatre. In 1942, again collaborating with Vernon Duke, he wrote the ill-fated The Lady Comes Across. The composer, in describing Latouche as having "unquenchable but ill-defined ambition," said, "He was very small, dark and stocky, with the face of a precocious infant. Johnny's mind was ever alert, his wit ever-sharp and often merciless; but the boy's essential goodness and kindness shone through his eyes. Extremely erratic by nature, Latouche worked spasmodically and swiftly on his poetry; short periods of work to be followed by long days and nights of blissful laziness and idle gallivanting."6

By 1945 Latouche was already a veteran and something of a celebrity of the Broadway stage. In the late autumn of that year, he began, under Watkins's guidance, to fashion his updated treatment of The Beggar's Opera.

From the John Gay original of 1728, several borrowings were obvious from the start, chiefly the satiric theme: the bourgeois and the criminal share the same vices and are, essentially, identical. Latouche's characters were lifted ready-made from the stock figures who peopled Gay's play. In Macheath, the amorous and wily gangster, he hit upon a character with electrifying appeal to jaded theatre audiences, weary of cliches about crime and punishment and ready for the "anti-hero," so well portrayed in the Hollywood film noir of this same postwar period; as one of Latouche's barbed lyrics had it:

Girls want a hero

Who's a cross between a Dillinger and Nero

A hard-boiled guy who has murder in his eye

And a pulse that never rises over zero.

In 1940, Latouche wrote the lyrics to Vernon Duke's score for the stage production of Cabin in the Sky, firmly establishing his credentials as a writer for the musical theatre. In 1942, again collaborating with Vernon Duke, he wrote the ill-fated The Lady Comes Across. The composer, in describing Latouche as having "unquenchable but ill-defined ambition," said, "He was very small, dark and stocky, with the face of a precocious infant. Johnny's mind was ever alert, his wit ever-sharp and often merciless; but the boy's essential goodness and kindness shone through his eyes. Extremely erratic by nature, Latouche worked spasmodically and swiftly on his poetry; short periods of work to be followed by long days and nights of blissful laziness and idle gallivanting."6

By 1945 Latouche was already a veteran and something of a celebrity of the Broadway stage. In the late autumn of that year, he began, under Watkins's guidance, to fashion his updated treatment of The Beggar's Opera.

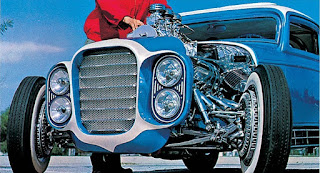

John Latouche

From the John Gay original of 1728, several borrowings were obvious from the start, chiefly the satiric theme: the bourgeois and the criminal share the same vices and are, essentially, identical. Latouche's characters were lifted ready-made from the stock figures who peopled Gay's play. In Macheath, the amorous and wily gangster, he hit upon a character with electrifying appeal to jaded theatre audiences, weary of cliches about crime and punishment and ready for the "anti-hero," so well portrayed in the Hollywood film noir of this same postwar period; as one of Latouche's barbed lyrics had it:

Girls want a hero

Who's a cross between a Dillinger and Nero

A hard-boiled guy who has murder in his eye

And a pulse that never rises over zero.

Likewise, Latouche took the rest of Gay's gamut of characters, from the outlaws to the in-laws; the politician Peachum and his daughter Polly; Lockit and his daughter Lucy, a chief of police and a whore, respectively; the madam Jenny and the thief Sneaky Pete (Filch in the original), and so on. Also preserved was the Beggar character who served, as in the original, as narrator and interlocutor.7

Latouche saddled his first draft with the tame title Street Music. In the original version of Act I, the Beggar sets the required tone of moral ambiguity, accompanying himself on guitar with "In Between":

Between the twilight and the nightfall

There's a time that's outside of time

When you feel yourself standing nowhere at all

And you watch the shadows lazily climb

Where there once was the sun

And now there is none.8

By a series of songs and dances, we are introduced to the other characters: "A Guy Name of Macheath," "Git Out" (Jenny), "When I Walk With You" (Macheath and Polly, the dominant romantic ballad of the show.9 We meet the colorful denizens of Macheath's gang and Lucy's whorehouse through a series of numbers, including "TNT," sung by the Cocoa Girl:

Auntie's in the loony bin

Uncle's on the drink

Granny's in the graveyard but

I'm in the pink

The folks are doing fine, you see

So baby, see me for your TNT.

Some of the best lyrics wound up sacrificed to the exigencies of production, among them the verse to "Loose Living":

I lunch on the succulent olives

That grow in a martini dry

The cherries that batten within a Manhattan

Bring a bright, rosy flush to my eye.

The fruit in a double old-fashioned

Keeps my golden tresses in curl,

For snacks at odd hours,

Oranges from whiskey sours

Help me to be a healthy American girl!

The middle scenes of the first act introduce the heavies, the shady politico Hamilton Peachum, his unabashed Mrs. ("Nothing Is More Respectable than a Reformed Whore") and the corrupt police chief, Lockit. They are played, even in the tensest situations, as comic characters, generally with satiric patter, slapstick routines, and intricate two- or three-part song arrangements. Among the latter, many are done in the manner of recitative ("Scrimmage," "Ore from a Goldmine," etc.), while others are cleverly pantomimed to the tune of musical instruments, with the bassoon and piccolo articulating a quarrel between Peachum and Lockit as they plot the sensational arrest of Macheath as a smokescreen to hide their own nefarious activities.

The first act ends with the hobo jungle scene, where Macheath's gang has gone into hiding and where, presently, they are joined by the entire company of doxies from Lucy's whorehouse. The plot development here, of course, is the betrayal of Macheath by Lucy and Mac's arrest, but the scene is most significant in its song and dance numbers, which include the poignant "On the Wrong Side of the Railroad Tracks" and the sly "Rooster Man," with its cock-and-hen rhumba accompaniment.

One clever lyric, later dropped from the show, celebrated the virtues of gang life while putting down the "straight life":

You wake up and breakfast on a cigarette,

A cup of bitter coffee and a bun.

You rush for a trolley that you never get;

When you do, it's an overcrowded one.

You push through a mob when you reach your street,

The elevator man don't say hello.

Then you chatter with the customers, so cordial and so sweet,

The kind of dopes you'd never want to know.

So you fret and you get in an awful stew,

And develop indigestion and a breakdown or two,

And you sleep with the nightmares ridin' over you,

And you struggle to a movie, and the ushers make cracks,

And you overpay your doctor just to tell you to relax.

How ducky!

Who lucky?

It must be me.

When you feel yourself standing nowhere at all

And you watch the shadows lazily climb

Where there once was the sun

And now there is none.8

By a series of songs and dances, we are introduced to the other characters: "A Guy Name of Macheath," "Git Out" (Jenny), "When I Walk With You" (Macheath and Polly, the dominant romantic ballad of the show.9 We meet the colorful denizens of Macheath's gang and Lucy's whorehouse through a series of numbers, including "TNT," sung by the Cocoa Girl:

Auntie's in the loony bin

Uncle's on the drink

Granny's in the graveyard but

I'm in the pink

The folks are doing fine, you see

So baby, see me for your TNT.

Some of the best lyrics wound up sacrificed to the exigencies of production, among them the verse to "Loose Living":

I lunch on the succulent olives

That grow in a martini dry

The cherries that batten within a Manhattan

Bring a bright, rosy flush to my eye.

The fruit in a double old-fashioned

Keeps my golden tresses in curl,

For snacks at odd hours,

Oranges from whiskey sours

Help me to be a healthy American girl!

The middle scenes of the first act introduce the heavies, the shady politico Hamilton Peachum, his unabashed Mrs. ("Nothing Is More Respectable than a Reformed Whore") and the corrupt police chief, Lockit. They are played, even in the tensest situations, as comic characters, generally with satiric patter, slapstick routines, and intricate two- or three-part song arrangements. Among the latter, many are done in the manner of recitative ("Scrimmage," "Ore from a Goldmine," etc.), while others are cleverly pantomimed to the tune of musical instruments, with the bassoon and piccolo articulating a quarrel between Peachum and Lockit as they plot the sensational arrest of Macheath as a smokescreen to hide their own nefarious activities.

The first act ends with the hobo jungle scene, where Macheath's gang has gone into hiding and where, presently, they are joined by the entire company of doxies from Lucy's whorehouse. The plot development here, of course, is the betrayal of Macheath by Lucy and Mac's arrest, but the scene is most significant in its song and dance numbers, which include the poignant "On the Wrong Side of the Railroad Tracks" and the sly "Rooster Man," with its cock-and-hen rhumba accompaniment.

One clever lyric, later dropped from the show, celebrated the virtues of gang life while putting down the "straight life":

You wake up and breakfast on a cigarette,

A cup of bitter coffee and a bun.

You rush for a trolley that you never get;

When you do, it's an overcrowded one.

You push through a mob when you reach your street,

The elevator man don't say hello.

Then you chatter with the customers, so cordial and so sweet,

The kind of dopes you'd never want to know.

So you fret and you get in an awful stew,

And develop indigestion and a breakdown or two,

And you sleep with the nightmares ridin' over you,

And you struggle to a movie, and the ushers make cracks,

And you overpay your doctor just to tell you to relax.

How ducky!

Who lucky?

It must be me.

The second act, beginning with Macheath's jailbreak and concluding with his entrapment, re-arrest and execution, offers less in the way of memorable song material. Such numbers in the first draft as "Boll Weevil" and "True Love Is Not an Atonement" were quickly abandoned, along with a gem of a number in which jailbirds voice their new-found satisfaction with life:

We don't want the wings of an angel,

We don't want the wings of a dove.

Don't wanna rise and shine like a B-29,

'Cause the jailhouse is the place we love.

We're sure of a roof when it's rainy,

We're certain of three meals a day.

The white and the black have a shirt on their back,

Which is more than honest people can say.

A little further on, another song, sung by Chief Lockit and also unfortunately deleted, comments on the show's philosophical underpinnings:

When you criticize this age

Do it discreetly.

Always sugar-coat your rage--

And cut throats sweetly.

There's a nervous little ghost

In every attic;

So with anyone you roast

Be diplomatic!

Though your phrases may be vague as can be,

Everyone will say, "the bastard's gunning for me!"

Other songs, including the trenchant "Lullaby for Junior," the witty "Women" (which eventually was assigned to the character Careless Love, as Sneaky Pete came to be renamed), and the beautiful and wistful "Brown Penny" (so used for both a coin-toss situation and Lucy's color) managed to survive the rigors of rehearsal and made their way into the Broadway production. All in all, Beggar's Holiday started out with a promising set of lyrics. All it needed was a musical score to match.

By the late summer of 1946, Latouche had completed a typescript to go into rehearsals with. Despite a number of serious flaws, particularly in the second act, his lyrics and libretto provided a witty and effective commentary on the modern city Big Time, particularly when wedded to music by that most quintessentially urban of modern composers, Duke Ellington.

|

| Duke Ellington

Ellington, now approaching the twentieth anniversary of his Cotton Club debut,

|

To some American critics he is the genius of his time, born to glorify Negro music. But to others, equally articulate, he is a figure grown fat with commercial success, a great jazzman who sold his music out to rehearsed arrangements and concert-hall pretensions.

To the latter accusation, Duke could do little but protest that his music had never really changed. "I'm not trying to convince anyone of anything," he said. "We're playing the way we feel like. Some of our pieces are just more extended and the ornamentation more mature." In truth, most of the "extended" works in Ellington's concert repertory consisted of short pieces linked by one means or another into the form of a "suite." Moreover, at this point in his career, Ellington was long past any fundamental changes.

True, like other bands engaged in the one-upmanship of the pop music market, the band's various horn sections were augmented by the addition of new personnel, sometimes resulting in a heavy, bloated sound in comparison to the lean perfection of earlier years. More and more, too, Ellington came to accept arrangements from outsiders, with the consequence that some of the band's performances sounded decidedly un-Ellingtonian. If the band had "grown fat" in this sense, the same was true of its boss, whose reputation as a gourmand was legendary. Duke weighed in now at well over 250 pounds, and the size of his ever-expanding wardrobe had perhaps become the most salient feature of the press ballyhoo about him.

The press yawningly reported Ellington's appearances on his annual concert tours, often sneering disparagingly at the "now easily-invaded Carnegie Hall." Now that the war was over, apparently, the symphony world had put its slogans of "racial unity" back in mothballs. Duke couldn't have cared less about the media stories, as he was riding the crest of his greatest popular success. Since the expiration in mid-1946 of his Victor recording contract, he had become a stockholder in the independent Musicraft record label under unusually favorable royalty terms, with stiff guarantees against declining sales. With Dr. Arthur Logan and Decca's Mayo Williams, he also invested at the launching of Sunrise Records. (Unfortunately, neither venture paid off,)

Duke's bookings kept pace with his new ventures. His itinerary for 1946 and 1947 traversed the country twice, and the band played every conceivable type of gig, from posh concerts in tux or tails to theatre dates and junior proms. For the time being, there was also national radio time sponsored by the U.S. Treasury Department. Life for Ellington was most assuredly on the upbeat; as far as he was concerned, there was no time like the present to commence a Broadway career, an opportunity that had not presented itself since Jump for Joy went belly-up on the Coast five years before. And from Perry Watkins's point of view, American music offered no better prospect for the sort of production he had in mind.

Near the end of September, it was reported that Duke had finally completed his score for "the new jazz version" of The Beggar's Opera and that he was ready to return to New York from his touring, in order to personally deliver the manuscript to the show's producers. Practice sessions were scheduled to begin around the first of October in preparation for an out-of-town opening, possibly in Boston, around November 11th. The show would be kept on the road for three or four weeks and then brought to New York in mid-December. He told the press that he planned to lose no time in getting together with his co-composer, Billy Strayhorn, to prepare the orchestrations.

It was late summer, 1946, when John Houseman, whom Watkins had known from their days together on the Negro Theatre Project, was brought in as director. Romanian by birth and British-educated, Houseman had been thrust, quite by chance, into American show business since the early 1930s. Since his WPA days, he had been a co-founder, along with Orson Welles, of the Mercury Theatre. In 1941, between spells in Hollywood as a highly successful producer, he was co-producer of the Broadway version of Richard Wright's Native Son. No stranger to controversy, Houseman had already had a considerable impact upon the theatre and, now in his mid-forties, was rightly regarded as a pioneer.

Watkins had first approached him for Beggar's Holiday during the rehearsals for Lute Song in the fall of 1945, and Houseman kept it in mind when he embarked for Hollywood to finish up a studio commitment there. When he returned to New York in the summer of 1946 to discuss the project further, he spoke to Ellington, who he soon learned was "one of the world's great spellbinders." As always, Duke was "hideously busy" and carefully insulated from the rigors and annoyances that frustrate the average person. His retinue consisted of people whose responsibility was to rouse him, choose his wardrobe, feed him, and in general move him through one day to the next. In this way, he explained to Houseman in confidential tones, he managed to preserve his sanity.

|

| John Houseman |

With Latouche, whose acquaintance Houseman had made some years before, there was almost from the beginning a clash of temperaments with truly disastrous results. Beyond this bare fact, one has to make up his own mind about who is to blame for the coming failure. In Houseman's eyes, Latouche was indolent, unreliable and dishonest; his promised drafts and revisions of the script never seemed to materialize. What little there was of the finished script, Houseman claims, was due chiefly to the efforts of himself and his assistant, Nicholas Ray.

Ellington, in his autobiography, Music Is My Mistress, describes Latouche in very different terms:

It was a great experience writing with a man like him, a man who is so imitated today by other people writing shows. He was truly a great American genius, and he was recognized as such, but he was not an aggressive man and he took it all in his stride like a true artist.10

Coming from Ellington, this was high praise indeed. Moreover, Duke, as if to defend Latouche against Houseman's accusations of irresponsibility, took pains to recognize his indefagitable energy and productivity as the lyricist for over fifty songs in Beggar's Holiday. While none of this settles the question of of authorship of the book, it does suggest a certain rift between Ellington and Houseman, something neither man has indicated. (Internal evidence-- the handwritten manuscripts which accompany the various typescripts of Beggar's Holiday-- leads to the conclusion that Latouche was the major, if not sole, author. The early drafts of Act II, however, confirm Houseman's memory of events: crucial scenes are either missing entirely or summarized in such a way as to be quite useless to actors in rehearsals.) Perhaps some part of the answer to what went wrong with the play resides here, in the distrust that developed between the director, on the one hand, and the lyricist and composer, on the other. In the midst of all this, it was imperative to begin the process of casting and rehearsals at once, particularly since Ellington's schedule, booked well into the next year, would not permit him to remain at hand much longer. First to be cast were the chorus and dance roles (The first versions of the script indicate these parts by the names of the actors, rather than the characters they play). By early October, while the script was still under frequent revision, the leading roles were ready to be cast.

|

| Marie Bryant |

Dancer Marie Bryant, with whom Duke had worked in Jump for Joy, was the first cast member hired, as the Cocoa Girl ("TNT"); the part of Macheath went to Alfred Drake, who had achieved fame four seasons earlier for his portrayal of the cowboy Curly in the original production of Oklahoma! Joining him were Libby Holman, in the role of Jenny; Avon Long (of Cotton Club fame and a revival of Porgy and Bess), as Careless Love ("Wanna Be Bad"). An up-and-coming dancer, Marjorie Belle, who portrayed The Girl at odd moments between dance routines, was also among the first cast.

Libby Holman, then 46, stepped into the leading lady role with the expectation that it could crown her long and illustrious career on Broadway. Although she is barely remembered now, Libby once basked in the kind of public glory that made Bette Davis and Tallulah Bankhead celebrities; she had attained stardom in 1929, with the Schwartz-Dietz Little Show; the following year, in Three's a Crowd, she introduced her most durable standard, "Body and Soul." Libby's private life, a long series of tragedies and emotional scars, had, by the mid-40s, made her nearly as notorious as she was then famous. 11

|

| Alfred Drake, Libby Holman, and Zero Mostel |

The remainder of the cast of twenty-eight was to be chosen during rehearsals in October. They included Jet MacDonald as Polly, Mildred Smith, a former high-school teacher from Cleveland, as Lucy; Rollin Smith as Chief Locket; and Dorothy Johnson as Mrs. Peachum. The role of Hamilton Peachum, requiring the sort of broad humor more common to burlesque than to musical theatre, went to Zero Mostel, then appearing nightly at Cafe Society as a stand-up comic. Beggar's Holiday was his very first theatrical role.

One by one, the various problems involved in production seemed to be solved, in some instances brilliantly. The first set designs by Perry Watkins, for example, were altogether lackluster; in stepped Oliver Smith, at that time co-director-cum-designer of the Ballet Theatre and the producer of Sartre's No Exit. Smith's designs for Beggar's Holiday were lavish and boldly original. There were revolving stages and scrims, stylized street corners and penthouses, fire escapes and hobo jungles, and, above it all, a panoramic suspension bridge casting its shadow over the dog-eat-dog world of the play. Valerie Bettis's choreography sparked the entire cast. "Rehearsals began deceptively well," Houseman recalled:

The quality and color of Ellington's music and the energy of our mixed cast almost made us forget the inadequacies of our book and the absence of a structured score... Even the book seemed to play fairly well at first. Zero's prodigious vitality and inexhaustible invention made the Peachum scenes work.

Mostel's scenes throughout provided the slapstick counterpoint to romantic comedy, with Zero mugging, whining, and generally hamming it up. The typical Peachum scene included a fast-paced and intricate number, with plenty of physical humor and stage business, such as "Peachum's Recitative: in Act I:

Peachum: Each maiden who is smart keeps a time-clock by her bed

Mrs. Peachum: Although you lose your heart, you should never lose your head.

Peachum: The market price of virtue is as high as Tel & Tel

Mrs. Peachum: And romance can never hurt you if you invest it well.

Polly: Perhaps I seem a fool

But I will not play your game,

My head can not be cool

When my heart is all aflame.

Mr. & Mrs. Peachum: In vain your parents lecture

And try to help you, Miss

As we both expect, you're

A sucker for a kiss.

We tell you he's a bounder

Your pickin's will be slim

But your heels are getting rounder

With every kiss from him.

Polly: I bow my head in grief, for the fickle hand of fate

Has robbed my darling thief of a love that came too late.

The flatfoot soon will chisel

His name upon a stone

In the hot seat he will sizzle

While I shiver all alone.

Oh, Polly-- poor Polly

A broken-hearted Dolly...

Mr. & Mrs. Peachum: We're getting apoplexy

In vain we storm and shriek

Because a guy is sexy,

You think that he's unique.

|

| "Under the Bridge Ballet" built suspense leading to Macheath's shootout with the forces of law and order. Precisely when the exhilaration and intensity of the first weeks began to wear and things began to go wrong is hard to say. To begin with, Latouche couldn't make up his mind how to end his play. In the course of three or four months, he had changed his mind three or four times, and each change necessitated an overhaul of the second act. The final scene begins with a chorus of newsboys and citizens singing of Macheath's impending execution while assorted vendors and hawkers peddle their wares to the crowd outside the prison walls. The various characters-- the Beggar, Lucy, Polly, Lockit, Peachum, and finally Macheath-- take their places for the grand finale. Macheath takes his leave of Lucy, Polly, and a number of lesser wives and is solemnly strapped into the electric chair. As the switch is pulled, flashpots under the chair discharge, and the stage is plunged into darkness. When the lights are brought up, behind the scaffolding for the chair we see the entire urban panorama, as in the Beggar's prologue. Macheath, still seated in the chair, now begins to launch into a sermon about who's really guilty for the crimes of modern society. Is it Peachum, who profits most from the underworld's evil doings? Is it Lockit, who "sells what's left of justice on the installment plan"? Is it Lucy or Polly, so intent on what ersatz happiness they can extract from life that they are unaware of the misery around them? No! The Beggar says: You see how it is, Mac. Look at the lathered pack of mankind, hysterical, jittery, anxious-- jumping over this way and that, snapping and biting at whatever passes before their furious jaws... looking for a blame in this man's color, a scapegoat in that man's race, running frantically before the shadow of their illogical fear-- trapped in the arid gullies of their hatred... Hear them howling in the smoky ruins of their world, Mac. See them sniffing relentlessly after the bloody spoor of guilt in the shattered houses and terrified streets... and always refusing to track it down to where it hides-- in the secret shadows of his own heart. The deed has been done by all of us-- the hates hated by all of us-- the bombs released, the triggers pulled, the mines laid, the victims destroyed-- by all of us. The one thing we share in this inequal world is guilt. But wait a minute. This was a Broadway musical: you couldn't preach to the audience, especially not about collective guilt. Latouche tried again. The trouble lay with the apparent incongruity between the medium and the message. Latouche, moreover, didn't really believe the collective guilt sermon himself, and he was astute enough to understand that there were some conclusions even "progressives" didn't want bandied about on Broadway. His first solution was to tinker with the Beggar, the "outside" character who dreams up this tale and is supposed to interpret it to the audience as a neat little moral at the end of Act II. The Beggar has functioned thus far as the author's mouthpiece, his go-between to the characters in the play proper. Latouche's first idea was to scrap most of his scenes and throw in new dialogue or more songs to cover the resultant gaps. There were other alterations, some of them rather drastic, such as killing off Careless Love, using his body as bait to entrap Macheath, and bringing him back to life for the grand finale. In this new version, as the climax approaches, Macheath bids a brave farewell to his wives and lovers ("After this-- the chair is an anticlimax!") Behind a scrim and seen by the audience in silhouette only, he then does the strapping-in number. The throwing of the switch is followed by a second of silence and total blackout, and then the chair becomes illuminated as a "huge, gaudy juke-box throne," in which now sits the Beggar, who says something about how you can damn near dream yourself to death. Here the author intrudes: FROM HIS BRIGHT-LIT THRONE (SPEAKING ACROSS THE DARKNESS AND ABOVE THE HEADS OF THE DIMLY-PERCEIVED ACTORS ON STAGE) THE BEGGAR HARANGUES THE AUDIENCE. HE RELATES HIS DAY-DREAM TO PRESENT-DAY AMERICAN LIFE; EXPLAINS HIS PHANTASY IN TERMS OF THE FASHIONS AND FOIBLES OF OUR TIMES. IT SHOULDN'T TAKE LONG-- NOT MORE THAN A MINUTE OF TIME-- BUT IT WILL POINT AND CLARIFY THE MEANING OF THE BEGGAR'S OPERA TODAY. (This speech is still being polished and worked on until the very last minute. It will depend to a great extent on the impact and reaction-quality of our play.) AT THE CONCLUSION OF HIS LITTLE SPEECH, THE BEGGAR, KNOWING THAT THE AUDIENCE OBVIOUSLY AND RIGHTLY EXPECTS, AGREES TO GIVE THEM ONE. THEY SHALL HAVE THE MOST GODDAMN HAPPY ENDING THEY'VE EVER SEEN. SO HERE GOES-- This time the sermon never materializes-- only the author's barest intention to create one, by and by. In the meantime, the Beggar proceeds to trick the audience into swallowing his non-existent sermon with some clever sleight of hand. The new make-believe ending has the various marriages annulled; both Peachum and Lockit receive comic justice, and then, for that last bit of razzle-dazzle, the Beggar is unmasked to stand revealed as Macheath, who runs off with all three of the leading ladies as the cast reprises the new finale, "Utopiaville" (which had usurped "On the Wrong Side of the Railroad Tracks" and was itself superseded by "Tomorrow Mountain"). However, even this bit of self-inflected schizophrenia wasn't enough to hide the contradiction it was intended to camouflage. At the time the show went into rehearsals in early October, Latouche gave up moralizing altogether and put his efforts into smoothing out the script's rough edges into something palatable to a Broadway audience. He threw in off-stage exchanges between "The Hero Maacheath" and "The Beggar Macheath," with a street ballet inserted for good measure. He envisioned spectacular lighting effects and dramatic transitions in staging. He scrapped the songs made obsolete by his revised plot-line and wrote new songs, as good or better, to replace them. But the one thing Latouche couldn't do was reconcile his aims with his means. The more he tried, the more he succeeded only in ballooning his play to interminable length and compounding the problems of dramaturgy. Lucy (Mildred Smith), Macheath (Alfred Drake), and Polly (Jet MacDonald) in "Duet of Polly and Lucy" At the same time, the lavish expenditures invested in scenery, cast, crew, and costumes had finally caught up with the company. Some time earlier, the checks had begun to bounce, and the creditors, the costume and scene shops, were threatening a suspension of services. The production was saved from financial disaster by roping in a wealthy investor, John R. Sheppard, Jr., who was described by Houseman as "a very strange rich boy," and "a drunken angel." Sheppard began throwing his money around with gusto, and for this he was credited as co-producer on the marquee, beneath the new title the show had given itself, Twilight Alley, a title derived from a lyric to "Utopiaville." All in all, the show had run up some $350,000in production expenses. Despite Sheppard's intervention, the show's finances remained touch-and-go through in out-of-town tryouts. Rehearsals in New Haven in late November took place on a bare stage, as the scenery was still not paid for. "In a series of desperate scenes of blackmail and tears," Houseman wrote, Sheppard "was separated... from a substantial part of his inherited wealth." With some $50,000 thus collected, the scenery arrived, was unloaded and erected over the next thirty hours. Time still permitted one technical rehearsal, which went flawlessly, but the cast's dress rehearsal, begun only eight hours before the opening curtain, had to be cut short. Alfred Drake was forced to improvise the sadly-aborted denouement "before an audience that included the usual number of vulturous ill-wishers from New York." At the conclusion of the performance, Houseman, Sheppard, Latouche, Ellington, and Nick Ray retired to "a blood-drenched" suite in the Taft Hotel to have it out at last. Houseman was of the opinion that further performances should be postponed but was overruled. All night long, over whiskey and sandwiches, contradictory views and acrid accusations were exchanged. As Ellington recalled: ...Nobody had a harsh word to say of anyone, until after the show had opened in New Haven... At a meeting after the show, the director was still asking for more music, as he had been up to and through over fifty songs. "What we need here is a song," he began right away. "Well, listen now, I love to write music," I answered. "Let's put ten new songs in the show. I'll sit here and write 'em tonight. But here is a man [Latouche] who has written the lyrics for over fifty songs. I just saw the matinee, and I couldn't hear the words. 13 And so it went; as Jon Bradshaw has reported in Dreams That Money Can Buy, Libby Holman was too old; the ingenue was too young; Zero Mostel was too zany; he was the best thing in the show; there were too many blacks; there weren't enough blacks... The combatants, overcome by fatigue, finally drifted away, having achieved nothing but bitterness for their long night. As if this wasn't enough, problems began to crop up among the cast as well. Amidst the intrigue of backstage romances and generally bad vibrations, Libby Holman began to lose her nerve. She resumed a heavy drinking habit and pretended not to notice the whispers about her age and reputation during the show's out-of-town floundering. Unable to fully enter her role, her performances were tentative and uncertain. Heartbreak and bloated egos hung over a show that seemed destined to fail. Beggar's Holiday went to Boston with its chin up, however. The cast salvaged its dignity, relied on discipline, and took the bad with the good. Behind the scenes, Houseman was quietly ousted and replaced as director by George Abbott. 14 Before long, Libby Holman was informed, in the most callous fashion, that she, too, was fired. This was the most bitter disappointment in a lifetime of sudden glory and equally sudden calamity. The hoe left by her absence crippled the production yet further, as no last-minute replacement could do justice to her role. Much of the show had been built around Libby, and her firing meant that much of her song material had to be jettisoned. An understudy, however talented, could hardly be expected to take her place. Play-doctor Abbott immediately came up with a prescription. "Let's forget about all these changes," he said, thumbing through the tattered and smudged pages. "Let's go back to the original script." But not a single copy could be found. Nobody had one: not Houseman, not Ellington, not even Latouche! Meanwhile, the New York opening was imminent. Observers of the theatrical world must have been taken aback to see the show's advertising during the last weeks of tryouts, running alternately as Twilight Alley and Beggar's Holiday, as well as finding the just-fired Libby Holman still listed in the cast. 15 It seems impossible that any show could have surmounted such confounding circumstances, but Beggar's Holiday kept its morale, and the long-awaited Broadway premiere came, not on December 26, as history has recorded it, but at a preview performance on Christmas night. Hindsight makes the debut seem more ominous now than it could have then: a benefit show for Paul Robeson's Council on African Affairs, an organization which, within the next few years would become a favorite target of the House Un-American Activities Committee investigations and of red-baiters everywhere. But in 1946 the benefit attracted no unusual attention. It was billed, in the Daily Worker and everywhere else, as a "Merry Xmas Night." The audience of liberal, progressive New Yorkers gathered that night to give their latest Broadway entry a gala send-off, little realizing that another age was dawning. Forty years later, however, one notes the event by casting a glance at an era of broken dreams, at the line separating post-war from Cold War. With Ellington almost the sole exception, most of the cast and staff were to be tarred with the Red Channels brush; Avon Long, Marjorie Belle, and John Houseman all had their share of political trouble and turmoil, and the story of Zero Mostel, who managed a spectacular comeback in the mid-1960s, is well known. 16 John Latouche's career lagged from then to his early death in 1956 , 17 while Libby Holman returned to the stage only once, in 1954, in a one-woman flop called Blues, Ballads and Sin Songs. But all this is getting ahead of our story. The opening night performance inspired rather polarized reviews from the New York critics. John Chapman, Brooks Atkinson, and Robert Bagar, in The Daily News, The Times, and The Herald-Telegram, waxed ecstatic. All of them praised the cast, the book, the staging, and the musical score. Chapman, whose column flatly declared the show "the most interesting musical since Porgy and Bess," singled out Duke Ellington for "refusing to follow the Tin Pan Alley pattern... If you are looking for a cut-and-dried hit, you can afford to skip it, but if you want something different you should go." Atkinson commented: Mr. Ellington has been dashing off songs with remarkable virtuosity. Without altering the basic style, he has written them in several moods-- wry romances, a sardonic lullaby, a good hurdy-gurdy, a rollicking number that lets go expansively... An angular ballet comes off his music rack as neatly as a waterfront ballad. No conventional composer, he has not written a pattern of song hits to be lifted out of their context, but rather an integral musical composition that carried the old Gay picaresque yarn through its dark modern setting. Bagar had kind things to say about Latouche's lyrics as well: (He) has brought the old story up to date, complete with cops and robbers and crooked bosses, a braggart of a gang-leader hero, Macheath, and numerous ladies of the evening... Together the music and text combine in as felicitous a wedding as the Broadway stage has offered in months... All in all, a remarkable fusion of talents, creative and performing, culled from superior white and Negro artists. If the reviews were therefore not uniformly bad, as John Houseman painted them, neither was it quite true, as Ellington claimed, that the show enjoyed a succes d'estime despite its failure to attract a large audience. Howard Barnes,Louis Kronenberger, Herrick Brown and Richard Watts, in The Herald Tribune, PM, Sun, and Post, respectively, all panned the show, but for different reasons. Barnes seemed offended by the very idea of "exploring the humorous possibilities of sex." complaining that such brothel settings as the show offered were inherently "tasteless and undramatic." Brown faulted the book, while Kronenberger rather perversely compared it to the 1728 original. Only one of the nay-sayers, the Journal-American's Robert Garland, was perceptive enough to explain the show's failure to live up to its own potential: What should have been a bright and bitter satire on the New York City Underworld of nowadays... ends up by being something else again... (In the second act) satire becomes slapstick. Bitterness disappears. Story-telling falls back on cops and robbers. Zero Mostel takes over... [The play] loses the courage of its unorthodox convictions. (italics mine) This hits the nail on the head. The dilemma of Beggar's Holiday raises the question of a "revolutionary" theatre, one which has occupied many a theoretician on the left. Imbedded in this question is a longer view of theatre history, one which takes in the devolution of the classic period of high tragedy and comedy into their democratic surrogates, melodrama and farce. Broadway entertainment, in this respect, is very much within the traditions set by the Victorians and Edwardians, and Beggar's Holiday was no exception. The problem facing Latouche was that he was an original playwright with a serious, "revolutionary" message: that crime is the very foundation of capitalism; while at the same time, the economic forces in play demanded that a Broadway success must adhere to an accepted formula: say nothing that could possibly offend anyone. How ironic that when a challenge was finally mounted successfully against the Broadway Brahmins and philistines, it once again came in the form of The Beggar's Opera. First produced in Berlin in 1928, the Brecht-Weill The Threepenny Opera immediately became the most successful European theatre production of this century and remained popular until the advent of Hitler. A New York Production in 1933, in an English translation faithful to the German original, closed after only twelve performances, chased out of town, as it were, by the choruses of shocked critics who considered it "sugar-coated communism." Nearly a quarter-century later, however, when the show opened off-Broadway in Marc Blitzstein's translation at the Theatre de Lys in March of 1955, it began a record-breaking run of 2,611 performances, buoyed by the enormous popularity of Kurt Weill's musical score, which included such classics as "Mack the Knife" and "Pirate Jenny." Brecht's solution was as revolutionary as his moral. The method was to alienate the audience from the performance by emphasizing the show's unreality. It appealed directly to the intellect of the audience, refusing to provide the solace of pity for the characters such as melodrama affords. Not for Brecht the sentimentality and superficiality of the theatre as he found it. Not for Brecht show-biz's rule number one, that the way to an audience's heart was to ingratiate oneself with it. The Threepenny Opera was a revolutionary play in many ways: it was conceived and born in a truly revolutionary period in modern history, that of the Weimar Republic; it shattered the boundaries of contemporary dramatic form; and its content was unabashedly radical. Beggar's Holiday shared only the last characteristic, and even that was conditioned by the bounds of Broadway practice and propriety. Taken as a whole, the play appeared radical chiefly in comparison to its competition in the musical theatre, which included Annie Get Your Gun, Carousel, Oklahoma! and Show Boat. Beggar's Holiday's radicalism-- what little was left of it-- was mostly indirect, its watchword Ellington's own: "Say it without saying it." Nevertheless, Beggar's Holiday, by daring to venture forth into territory never before brought to the attention of a Broadway audience, set standards of its own. As a musical truly ahead of its time, it deserves recognition as the precursor of such socially conscious productions as West Side Story and Cabaret. In its bold confrontation of American racial and political taboos, it might have found a more responsive audience in the late '60s or early '70s. Perhaps it's not too much to hope that, sometime in the future, American theatre-goers might yet vindicate Beggar's Holiday. NOTES: 1. Perry Watkins, "Holiday Is Bi-Racial Production." Chicago Sun, April 6, 1947, p. 29. 2. Watkins, ibid. 3. Watkins, ibid. 4. Watkins, ibid. 5. This piece eventually was transformed and re-christened "Ballad for Americans" and led a second life as a popular wartime "protest" vehicle, as sort of paean to the innate virtues of the freedom-loving American masses. In this form it may be heard on Vanguard VSD 57/58, The Essential Paul Robeson. 6. Vernon Duke, Passport to Paris. 1955, Little, Brown, Boston. 7. Latouche managed to retain much of the flavor of Gay's ballad opera by lifting some titles practically outright; compare Latouche's "The Employments of Life," "Ore from a Gold Mine," and "Rooster Man"-- to cite only a few-- to Gay's "Through all the employments of each," "A maid is like the golden ore," and "Before the barn-door crowing, the Cock by Hens attended." 8. A notation on the typescript indicates that this song was, at least in part, the work of Luther Henderson. 9. Between the first draft of Beggar's Holiday and the version which eventually opened on Broadway, the most significant change was in the treatment of Lucy's character. When, in the course of rehearsals, Libby Holman was cast in the part of Jenny, the latter was elevated to the starring role, replacing Lucy (Mildred Smith) as the madam and Macheath's nemesis. 10. Duke Ellington, Music Is My Mistress, pp. 185-186. Doubleday & Co., Garden City, N.Y. 11. In 1931 Libby Holman married Smith Reynolds, the tobacco heir. Six months later he was shot to death; Libby and Smith's best friend were indicted on murder charges. In the midst of a growing scandal, the Reynolds family exerted their influence to prevent the case from going to trial, but Libby's career was stalled for the rest of the decade. In the later 1930s and 1940s, she became a mainstay of cafe society and in the 1950s had a long involvement with Montgomery Clift. Several others in her life also suffered violent deaths, including her own son. After the Beggar's Holiday debacle, Libby again made her living as a night club entertainer. Her biography, Dreams That Money Can Buy by Jon Bradshaw (Morrow, 1985), was titled after a 1948 film in which she appeared with Josh White. 12. John Houseman, Front and Center, pp. 188-196. 1979, Simon and Schuster, N.Y. 13. Ellington, ibid. 14. The New York playbill mentions neither Houseman nor Abbott. Nicholas Ray is given sole credit as director. 15. Under the title Twilight Alley, the show was supposed to have opened at the Harlem Opera House during the third week of December, but apparently never did. By the time it reached Broadway, it was again titled Beggar's Holiday. 16. Avon Long, cited by the red-hunters for his membership on the Council for African Affairs, suffered a long career lapse until the 1970s, when he appeared on Broadway again in Treemonisha and Bubbling Brown Sugar. Alfred Drake was the star of Cole Porter's smash hit Kiss Me Kate, but during the decade that followed, I can find no television credits-- a totem of show-biz success-- for him or any of the others cited above. It may be worth noting that the only Hollywood film that Drake made (Tars and Spars) was in 1944. 17. John Lastouche's credits after Beggar's Holiday included Ballet Ballads (1948), The Golden Apple (opera, 1954), The Vamp (1955), The Ballad of Baby Doe (opera, 1956), and The Littlest Review (1956). In 1956 he was also a part of a team of lyricists working on Leonard Bernstein's Candide. He died August 7, 1956. ADDENDUM (1987) The New York production closed after fourteen weeks, in mid-March, 1947, but there was a brief coda to follow. With a few cast changes, most notably the substitution of Claudia Jordan for Jet MacDonald, the show opened April 5, 1947, Easter Sunday, at the Shubert Theatre in Chicago. The show made no more headway there than it had on Broadway and died unmourned, even by its own company. THE MUSIC Considering what he had to gain from the success of Beggar's Holiday, the degree to which Duke Ellington ignored this work in the repertory of his band is remarkable and puzzling. A check of the copywright registrations reveals that the bulk of the music and lyrics was never copyrighted, much less published. Some of the published material was put out by Chappell in a volume titled A Collection of Songs from Beggar's Holiday. More, some two score tunes in all, were published individually. Moreover in the year 1947, While Duke was under contract to Columbia Records, only five of the show's tunes were recorded in the studios; somewhat surprisingly, none of them were tunes singled out for praise by the critics. More surprising yet, although that year is relatively well-represented in the Ellington discography by non-commercial recordings (radio airshots, concert performances, broadcast transcriptions, and the like), only two examples are known of the band promoting this music in one of these ways. The first was a concert, featuring a Down Beat awards presentation, at the Chicago Civic Opera House on February 2, 1947; the Beggar's Holiday medley included "Take Love Easy," as a short piano introduction, into "When I Walk With You," a vocal performance by Marion Cox; "Tomorrow Mountain," as an orchestral bridge containing a trombone solo by Lawrence Brown; and "Take Love Easy," sung, as in the studio recording by Kay Davis. The other instance was the band's December concert at Carnegie Hall, which featured vocalist Dolores Parker on "He Makes Me Believe He Is Mine." Is it possible to conclude that Ellington was so embittered by his own experience with the play that he wanted to bury even the memory of the show? "Brown Penny," in another Strayhorn arrangement, was recorded in three takes at the October 2 session. Although the recording benefitted from a tender, understated arrangement, with Strayhorn at the piano, and an exceptional vocal by Kay Davis, it was not released anywhere in the world until after Ellington's death. "He Makes Me Believe He's Mine," recorded November 11, is another case in point. This ballad, probably a late addition composed for Bernice Parks, who replaced Libby Holman in the role of Jenny, perfectly combines Ellington's bluesy, wistful melody with Latouche's lyric of a whore scorned once too often: I'd kinda given up my faith in myself, I've had a lot of trouble He seems to know the secret longings I feel, And he makes me believe they are real. The vocal chorus by Delores Parker does justice to the fine lyric, and trombonist Lawrence Brow is at his melodic best on the poignant release. Overall a fine performance, this recording has never been released by an American record company. The same singer was present at the November 14 session on "Take Love Easy," which in the show was a sexy, suggestive bump-and-grind number performed by Marie Bryant. Both Miss Parker's interpretation and Ellington's tempo and arrangement stray from this mood, however, and the result is a bouncy, cutesy rendition which is saved only by Johnny Hodges's effervescent performance on alto saxophone. A much better version was recorded in Paris, with Alice Babs and a small group of local musicians led by Ellington, in a sultry cionception closer to the original intention. This series of five numbers recorded by the Ellington band in 1947 virtually marked the end of the composer's involvement with his score for Beggar's Holiday. With the exception of instrumental performances of "Brown Penny," subsequent returns to the material were almost non-existent. Other performers, however, did manage to include some numbers in their repertory: Lena Horne recorded a vocal rendition of "Tomorrow Mountain" on her Stormy Weather LP for RCA in 1956; Libby Holman recorded "In Between" in 1965, just a few years before her death. Somewhere there may exist recordings by other artists, but I cannot confirm them. As for the rest, only the music manuscripts remain, and of the reputed seventy-eight numbers Ellington composed for the show, fewer than two dozen have turned up thus far. Whether any of the remaining music will ever be performed again, only time can tell. N.B.: "I Want a Hero" and "In Between" by Duke Ellington & John Latouche. Copyright 1947 by Mutual Music Society, Inc. Copyright renewed, assigned to Chappell & Co., Inc. and Fred Fisher Music Co., Inc. International copyright secured. All Rights Preserved. Used by permission. ADDENDUM (2019) The foregoing was published in the new renaissance, vol. VII, No. 1 (fall, 1987), by the good graces of its editor, Louise Reynolds. I wrote with the aim of making my work indispensable for others investigating the subject further. I haven't yet achieved that-- though it's been thirty years-- but I did receive a citation in John Franceschina's Duke Ellington's Music for the Theatre, McFarland, 2001. In the text, I'm identified as a "theatre historian." Fooled 'em again, by God. My piece neglected to point out the symmetry between "In Between" and "Tomorrow Mountain." They are inversions of each other: the verse of one forms the chorus of the other. Consider it said. Another discovery: the lyric to "Brown Penny" was written by neither John Latouche nor Billy Strayhorn: it's an almost word-for-word copy of a poem of the same title by William Butler Yeats, widely anthologized (it was in the British Lit textbook I used back in the day). The most serious omission, however, was my failure to probe more deeply into Billy Strayhorn's significant contribution (detailed in Walter van de Leur, Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn, Oxford 2002) to the score of Beggar's Holiday. His themes included "Boll Weevil Ballet," "Brown Penny," "Cream for Supper," "Fol-De-Rol-Rol," "Girls Want a Hero," "Let Nature Take Its Course" (a much older song that made its way into the show at some point), "On the Wrong Side of the Railroad Tracks," "Thirteen Boxes of Rayon Skirts," "Through All the Employments," "We'll Scratch Out His Eyes," "Wedding Ballet," and "You Wake Up and Breakfast on a Cigarette." David Hajdu's Strayhorn biography (Lush Life, Farrar, Strauss Giroux, 1996), perceives, moreover, an incipient rift between Strayhorn and Ellington over the matter. On the Broadway program, Strayhorn receives credit for orchestrations only. Hajdu quotes set-designer Oliver Smith: "Billy didn't say 'boo' about Duke or how the credits would read the whole time... But on opening night on Broadway, there was a grand, gala party. Duke was there in all his splendor, receiving his public... Billy said to me, 'Let's get out of here.' I said, 'but the party's just starting.' And he said, 'Not for me, it isn't.' I told him no, I really should stay, and he walked away and out of the theater alone." Seven years after the publication of this article, in 1994, a new staging of Beggar's Holiday was mounted by the Pegasus Players of Chicago. One of the show's original producers, Dale Wasserman, was on hand with his "new" book and libretto (which, for the most part, used the John Latouche original but claimed credit for himself.) I was on hand for a rehearsal at that time, sitting next to Wasserman, who disparaged the cast as "amateurs." At that point, I recused myself from any further involvement with the revival. (Wasserman also "borrowed" the 8 x 10 cast photos I used in the article. What the hell, he's dead now: What goes around comes around.) These links are to contemporary comments from Chicago Tribune columnists: Howard Reich's 1994 Wasserman interview Richard Christiansen's 1994 review |

IN ROTATION:

Life in the UK grinds on through the Twentieth Century, and our ordinary hero chooses to ignore or explain away his servile predicament. "Let all the Chinese and the Spanish do the fighting. They'll never find us," goes the lyric to "Driving," as his family enjoys a picnic in the countryside.

OUR CAR CLUB:

NEXT: My Bitching At The Penguin Guide To Jazz

- Sarah Vaughan, After Hours (Roulette, 1961), with Mundell Lowe, gtr; George Duvivier, b.

This one has been dear to my heart from the beginning. My first copy was a budget-label (EMUS) LP, purchased in Oak Park, Illinois, sometime in the 1970s. The CD reissue adds a totally unnecessary and distracting bonus track, "Through the Years"; the album ends properly with "Vanity," one of Sass's most affecting performances. Her interpretations of the two Ellington selections, "Prelude to a Kiss"and especially Sophisticated Lady," are definitive in my book. The program is a demonstration of intimacy. Other than one brief guitar solo, the accompanists are content to support the diva. (The following year, a similar album, Sarah + Two, came out on the same label, with West-Coast sidemen Barney Kessel on guitar and Joe Comfort on bass. Another treasure.)

- Gal Costa, Gal Canta Caymmi (Philips/ Polygram, 1975)

- Elis Regina, Vento de Maio (EMI, 1980)

- The Kinks, Arthur (Pye/ Castle, 1969)

Thinking I was ordering the new, double-disc "Deluxe" reissue, I wasn't very disappointed to receive this earlier, single-disc reissue. Along with the original album, in stereo, the set offers bonus tracks, including mono versions of several tunes, plus mono and stereo versions of such contemporaneous songs as "Plastic Man,"and "This Man He Weeps Tonight." The set ends with a previously unreleased track "The Shoemaker's Daughter."

Now the album proper: it's one of the finest Kinks albums, which is saying a lot. The natural inclination was, and is, to compare it to Tommy, The Who's so-called rock opera. That release, in a double-LP set, a misconceived epic about "that deaf, dumb, blind kid'" spiritual redemption, was a windy, overstuffed, gassy propaganda track for whoever Pete Townsend's guru at the time was.

Not so Arthur. Conceived as a soundtrack to a television production that was never completed, it tells the story of an ordinary Englishman who has survived both World Wars, the Great Depression between them, and an unhappy present existence in his heavily mortgaged "Shangri-La." Starting with the anthemic tribute to Victoria" and her empire where "the sun never sets," Ray Davies's lyrics do not spare the title character. Arthur's God-and-country idealism is set against the brutality and cynicism of the politicians and military leaders who led an entire generation to the slaughter of war. As the line goes in "Yes Sir, No Sir":

If the scum are going to make the bugger fight,

We'll be sure to have deserters shot on sight.

If he dies, we'll send a medal to his wife.

Life in the UK grinds on through the Twentieth Century, and our ordinary hero chooses to ignore or explain away his servile predicament. "Let all the Chinese and the Spanish do the fighting. They'll never find us," goes the lyric to "Driving," as his family enjoys a picnic in the countryside.

OUR CAR CLUB:

- Duke Ellington & His Orchestra, ...And His Mother Called Him Bill (RCA, 1967)

There's something to be said for not fooling around with the original track order on a CD reissue, and this is a perfect case in point. The producers chose, rather, to program this tribute to Billy Strayhorn, begun only a few months after his untimely death, in order by recording session. The original producer programmed the album carefully as eleven orchestral tunes, followed by an unforgettable Ellington solo piano performance of "Lotus Blossom." In listening to it, we keenly feel Duke's expression of grief, while in the background we hear quiet conversations and the sound of musicians packing up their instruments at the end of the session, almost as if we're ourselves present in the studio. The CD reissue includes a later recording of the same tune, but by a trio comprised of saxophonist Harry Carney, bassist Aaron Bell, and Ellington on piano: a good enough performance, but not nearly as emotionally powerful as the earlier take.

What made the producer select the solo performance? It's hard to understand why another version was recorded at all.

"Lotus Blossom"

What made the producer select the solo performance? It's hard to understand why another version was recorded at all.

NEXT: My Bitching At The Penguin Guide To Jazz

In my rotation:

- Duke Ellington, Beggar's Holiday (my own compilation)

Appropriately for this post, I brought out this omnibus, assembled thirty-odd years ago to hear nearly every tune from the show I could get my hands on. I started with the 1946 cast recordings (reissued by Blue Pear Records, unfortunately after the article had been published) on which Libby Holman had already been replaced by Bernice Parks in the role of Jenny Diver. The other cast members participating were Alfred Drake, Avon Long, Jet MacDonald, Dorothy Johnson, Marie Bryant, and Mildred Smith, in the roles of, respectively, Macheath, Careless Love, Polly Peachum, Mrs. Peachum, the Cocoa Girl, and Lucy Lockit. No Zero Mostel, sad to say. A lucky find, coming along when it did.

Following this is Libby Holman's latter-day (1965) recording of "In Between," on the album Something to Remember Her By, and Lena Horne's version of "Tomorrow Mountain" from her Stormy Weather album on RCA in 1956. Dick Buckley's radio show provided an excerpt from a Down Beat awards ceremony at the Chicago Civic Opera House that included a medley of "Tomorrow Mountain" (sans vocal), "When I Walk With You," and "Brown Penny," the latter tunes featuring the voice of Kay Davis. Then come the only five studio recordings plus alternate takes, all from 1947 on Columbia, that the Ellington band made of tunes from the show, including Billy Strayhorn's magnificent arrangements of "Brown Penny" and "Change My Ways." The first disc concludes with a 1959 recording of "Brown Penny" by the Ellington band and a sexy rendition of "Take Love Easy" by Alice Babs on her 1963 album with Ellington, Serenade to Sweden.

The second disc is a little more problematic, beginning with my own piano renditions (some rather painful to hear) of the sheet music-- for five tunes otherwise not recorded-- provided on microfilm by the New York Public Library. The bulk of the tracks remaining come from Chicago's Pegasus Players in rehearsal for a 1994 revival of the show. (While attending, I sat next to Dale Wasserman, one of the original production's producers and a thoroughly unpleasant man.) The disc ends with four tracks by the Dutch Jazz Orchestra on their series of Billy Strayhorn tunes.

- Lawrence Welk & Johnny Hodges (Dot, 196?)

I received this from ejc, on a needle-drop cassette (It can be observed that the title changed when the record was reissued on CD.) There are no accordions featured here, thank God; the large string ensemble features orchestrations by many distinguished arrangers, including Benny Carter, Russ Garcia, and Marty Paitch.

Hodges plays impeccably throughout, but at times the orchestra induces boredom. Some of the featured tunes are oddities, such as "Fantastic, That's You," "Haunting Melody," "When My Baby Smiles at Me," and "Canadian Sunset, " but it's reassuring to hear Hodges play on the Ellington compositions "I'm Beginning to See the Light" (on which he played the original 1944 alto solo), "Sophisticated Lady" and "In a Sentimental Mood" (where he steps into the role originally occupied by his section-mate, Otto Hardwicke).

- Duke Ellington, Happy-Go-Lucky Local (Musicraft, 1946)

This CD comprises most, if not all, the music the Ellington band recorded for the Musicraft label in 1946. At that time, the band was a rather bloated aggregation of between seventeen and eighteen pieces: five or six trumpets (Francis Williams is incorrectly identified as Cootie Williams in the personnel listings), three trombones, five reeds, and four rhythm players. Likewise, the recordings themselves were sometimes extended to both sides of a ten-inch, 78-rpm record, with two-part titles like the title tune (extracted from Duke's current concert piece, The Deep South Suite), "The Beautiful Indians, and Billy Strayhorn's Overture to a Jam Session.

Throughout the program, but most particularly on "Happy-Go-Lucky Local," the bassist Oscar Pettiford puts forward an exceptional performance, continuing the modern trend first demonstrated in the orchestra by Jimmy Blanton. Strayhorn contributes a second composition, the puckish "Flippant Flurry," featuring clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton in another fine performance. Three vocalists appear, including soprano Kay Davis's lovely, wordless singing on The Beautiful Indians, Part 2: "Minnehaha," Al Hibbler on "It Shouldn't Happen to a Dream," and the redoubtable Ray Nance on "Tulip or Turnip."

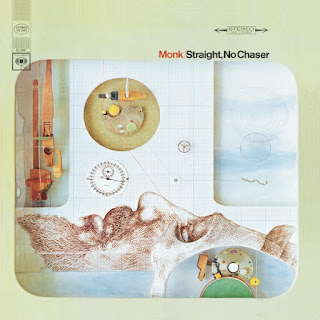

- Thelonious Monk, Straight, No Chaser (Columbia, 1966-1967)

This recording, in its original LP form, is a very old friend of mine. It features Monk's regular quartet, consisting of saxophonist Charlie Rouse, bassist Larry Gales and drummer Ben Riley. The CD reissue features full versions of tunes (most notably "Japanese Folk Tune") that were abridged in the original release, plus the bonus tracks "I Didn't Know About You" (alternate take) and the first recorded performance of Monk's "Green Chimneys." The former tune, in its original issue (take 4), was my first introduction to the Ellington classic, and has long been my favorite track on the album.

- Woody Shaw, Blackstone Legacy (Contemporary/ OJC, 1970)

This recording was not the first one by Shaw under his own name, but it was the first to be issued. Here the trumpeter leads a sextet including saxophonists Gary Bartz and Bennie Maupin, pianist George Cables, drummer Lenny White, and a team of bassists, Clint Houston and the veteran Ron Carter.

The five-year interval between his first effort, Cassandranite, and this album is telling; Blackstone Legacy represents a step forward from the hardtop Shaw had been playing, into another territory entirely. Here his band avails itself with the sort of shifting time-signatures I associate with the music of Charles Mingus.

More to the point, perhaps, is this record's huge debt to the recently-issued Bitches Brew by Miles Davis, which propelled the fusion trend of the '70s for most jazz artists of the time. Unlike the others, however, Shaw mostly eschewed the trendy electronic instrumentation of the time to explore the sort of extended composition put forward by John Coltrane in the '60s, including his proclivity for spiritual expression. This is the sort of music Shaw would create for the rest of his career.

Shaw's compositions here include the title tune, "Lost and Found," "Boo-Ann's Grand" (reflecting the changing moods of his wife, much in the fashion of Coltrane's "Naima"), and the tribute to one of his first mentors, "A Deed for Dolphy." Two charts by Cables, "Think on Me" and ""New World," complete the set.

This CD reissue of what originally had been a two-LP set includes a generous 79 minutes of music, although, in order to accommodate all of the tunes, two of them had to be trimmed to a slightly shorter length.

The five-year interval between his first effort, Cassandranite, and this album is telling; Blackstone Legacy represents a step forward from the hardtop Shaw had been playing, into another territory entirely. Here his band avails itself with the sort of shifting time-signatures I associate with the music of Charles Mingus.

More to the point, perhaps, is this record's huge debt to the recently-issued Bitches Brew by Miles Davis, which propelled the fusion trend of the '70s for most jazz artists of the time. Unlike the others, however, Shaw mostly eschewed the trendy electronic instrumentation of the time to explore the sort of extended composition put forward by John Coltrane in the '60s, including his proclivity for spiritual expression. This is the sort of music Shaw would create for the rest of his career.

Shaw's compositions here include the title tune, "Lost and Found," "Boo-Ann's Grand" (reflecting the changing moods of his wife, much in the fashion of Coltrane's "Naima"), and the tribute to one of his first mentors, "A Deed for Dolphy." Two charts by Cables, "Think on Me" and ""New World," complete the set.

This CD reissue of what originally had been a two-LP set includes a generous 79 minutes of music, although, in order to accommodate all of the tunes, two of them had to be trimmed to a slightly shorter length.

- Harry Nilsson, KNNILLSSONN (RCA, 1977)

One of Nilsson's late '70s releases, this recording lacks the broad, beautiful upper range of his vocals; indeed, at times it settles for a delivery that is half-sung and half-spoken. That said, there is no diminution of his compositional ability or his emotional effectiveness. The writing and instrumental accompaniment are strong throughout.

Some of these songs continue the vaudeville reminiscences employed from the beginnings of Harry's career, but the gorgeous "All I Think About Is You," the first track, completely captures the heart with his plaintive low-register singing. Likewise does "Perfect Day" and "Who Done It," a country reel enhanced by synthetic strings.

Some of these songs continue the vaudeville reminiscences employed from the beginnings of Harry's career, but the gorgeous "All I Think About Is You," the first track, completely captures the heart with his plaintive low-register singing. Likewise does "Perfect Day" and "Who Done It," a country reel enhanced by synthetic strings.

- Duke Ellington, Black, Brown and Beige (cassette compiled by Sjef Hoefsmidt)

This cassette was Sjef's gift to the members of the Duke Ellington Music Society, which thrived for many years under his leadership.

The enclosed notes and track listing make further comment unecessary, except to point out that the sound quality of the '60s and '70s recordings is far superior to the Carnegie Hall recording of 1943, as one would expect. "New" material from the 1980s series of Danish Radio broadcasts is used liberally. The excerpts included on the 1944 Victor double-78 rpm issue are fine, but Ben Webster, by the time it was made, was unfortunately no longer in the band, nor was singer Betty Roché. As controversial as the suite was at its first performance-- panned by most classical music critics and more than a few jazz writers-- it was groundbreaking at the time, both symbolically and musically, and it remains an Ellington composition of the first order.

- Thelonious Monk, Underground (1967)

with Charlie Rouse, ts; Larry Gales, b; Ben Riley, d.

Despite the garish sleeve photo, the music here is fine. Original LP tracks include "Thelonious," "Ugly Beauty," "Raise Four," "Boo Boo's Birthday," "Easy Street," "Green Chimneys" (a robust version of a tune previously recorded and included on the CD reissue of Straight, No Chaser see above), and "In Walked Bud."

Despite the garish sleeve photo, the music here is fine. Original LP tracks include "Thelonious," "Ugly Beauty," "Raise Four," "Boo Boo's Birthday," "Easy Street," "Green Chimneys" (a robust version of a tune previously recorded and included on the CD reissue of Straight, No Chaser see above), and "In Walked Bud."

- Woody Herman, Jazz Hoot (Columbia, 1965-1967)/ Woody's Winners (Columbia, 1965); both on Collectables CD

The fine rhythm section (pianist Nat Pierce, bassist Anthony Leonardi, and drummer Ronnie Zito) inspires the rest of the band to blow their butts off. Woody's unanticipated vocal on Lee Morgan's "The Sidewinder" manages somehow to import the Brazilian tune "O Pato" ("The Duck").

No comments:

Post a Comment