Winter, 1991

While reading Baugh and Cable's History of the English Language, I was both surprised and a little annoyed to find no mention of the Yiddish language in either of the two places I had expected to find it. I searched the first chapter for the relationship of Yiddish to the Indo-European family of languages, which has since medieval times shaped and nurtured it; I perused the final chapter on the development of American English, hoping to find at least a word on the impact of Yiddish. Both times I came up empty, and my conclusion is that Yiddish is difficult to classify and subtle in its influence upon American English.

My own knowledge of Yiddish has never been extensive, though I grew up in proximity to Yiddish speakers. I remember hearing from my parents such choice tidbits as "Gei kochen ahfen yom," "Is nisht gefiddelt," "A kocher nemt a pisher," and "Ich hab dir in bud," but only later came to realize how much of it was obscene. My parents, both first-generation American-born Jews who ordinarily used garden-variety midwestern American English, used Yiddish as a code that their children could not understand, so we picked it up only in dribs and drabs.

My mother's parents, however, brought Yiddish with them from Europe as their primary language, though both of them could speak Russian and became proficient in English. My grandmother would sit at her kitchen table, sipping her tea through a sugar cube as in the Old Country, reading her copy of Vorwarts with column upon column of strange Hebraic characters without vowels.

For second-generation American Jews such as myself, religious education was in Hebrew, not in Yiddish. Hebrew, moreover, was the revived language of the modern state of Israel, while Yiddish appeared to be an idiosyncratic expression of survivors of the European shtetl and ghetto. Clearly, there was a generational pattern at work pertaining to Yiddish in America.

Perhaps the major reason for the reluctance of our textbook authors to discuss Yiddish is that it appears to be a linguistic and historical anomaly. It did not receive its distinctive characteristics before the eleventh century, when Jews were invited from the Rhineland to Poland and Russia as a merchant class in between the nobles and the serfs. Yiddish developed as a peculiar amalgam of Indo-European and Semitic languages, Hebrew ion its orthography, Low German in much of its vocabulary and syntax, with a leavening of Hebrew and Aramaic from the Scriptures and Talmud, and later a heavy overlay of Slavic and a few Romance elements. Until quite recently, it was regarded as essentially a folk-tongue without a written grammar and a language that seemed to defy strict grammatical analysis.

Over the centuries between the Middle Ages and the Second World War, Yiddish produced a very rich literature of folksongs, tales, and folklore. German-Jewish literature, except for the Hebrew lettering, differed little from its gentile milieu, unlike its counterpart in Poland and points east. It was the spoken language of the masses of European Jewry up until the Holocaust, surviving even the Haskalah, the mass enlightenment movement of the late nineteenth century led by Moses Mendelssohn, which translated modern European literature into Yiddish. The 1860s and '70s brought a temporary decline of Yiddish, as Russian schools and culture were opened to Jews, but by the 1880s Russian pogroms facilitated its revival. The flowering of Yiddish literature, in both Europe and America, took place in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Yiddish theater, influenced by the works of Tolstoy, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, and Chekhov, likewise flourished for many years.

The nemesis of Yiddish language and culture, particularly in America, has been the acceleration assimilation of Jews into the mainstream of modern secular society. Aside from the shrinking immigrant generation served by the Vorwarts, the chief medium for the transmission of Yiddish language in America has been show business, particularly the work of Jewish stand-up comedians of the second or third American-born generation. Through them there has come about in this country a hybrid, which some have dubbed "Yinglish," wherein the expressiveness of the Yiddish language is used to pepper English for mass-media consumption. It is primarily through show-business usage that some five hundred Yiddish expressions-- such terms as schmaltz, goyish, and goniff have entered the English language and earned listings in the Oxford English Dictionary. Ironically, many of the individuals who helped familiarize America with such Yiddishisms, such as the comic Lenny Bruce, learned them only at second-hand and used them onstage in place of taboo English expressions.

- Carl Perkins, Introducing Carl Perkins (Dootone/ Fresh Sounds, 1956)

I seldom play this album, though it is often praised. The title track is mesmerizing; hardly a day goes by without my humming the guitar line or mouthing the lyrics. Most of the rest bores me, especially compared to Beef's immediately previous release, the double LP Trout Mask Replica. But "Space Age Couple" ("whyn't you flex your magic muscle") has become one of my mantras. A few of the tunes seem just plain silly, but all the instrumentals are good.

- The Kinks, The Kinks Present Schoolboys in Disgrace (RCA Victor, 1975)

- Count Basie and His Atomic Band, Complete Live at the Crescendo, 1958 (Phono)

This recent double-CD release is an important find. This performance took place on June 23, 1958, at Gene Norman's Crescendo nightclub in Hollywood.

- Ari Barroso, ???? (???, 1930-1942)

Lightly and Politely

- Carl Perkins, Memorial (Fresh Sound, 1956, 1957)

- Tokishko Akiyoshi, Toshike Mariano Quartet (Candid, 1960)

- Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra, Featuring Lew Tabackin, Desert Lady/ Fantasy (Columbia, 1993)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-10980300-1507587955-3310.jpeg.jpg)

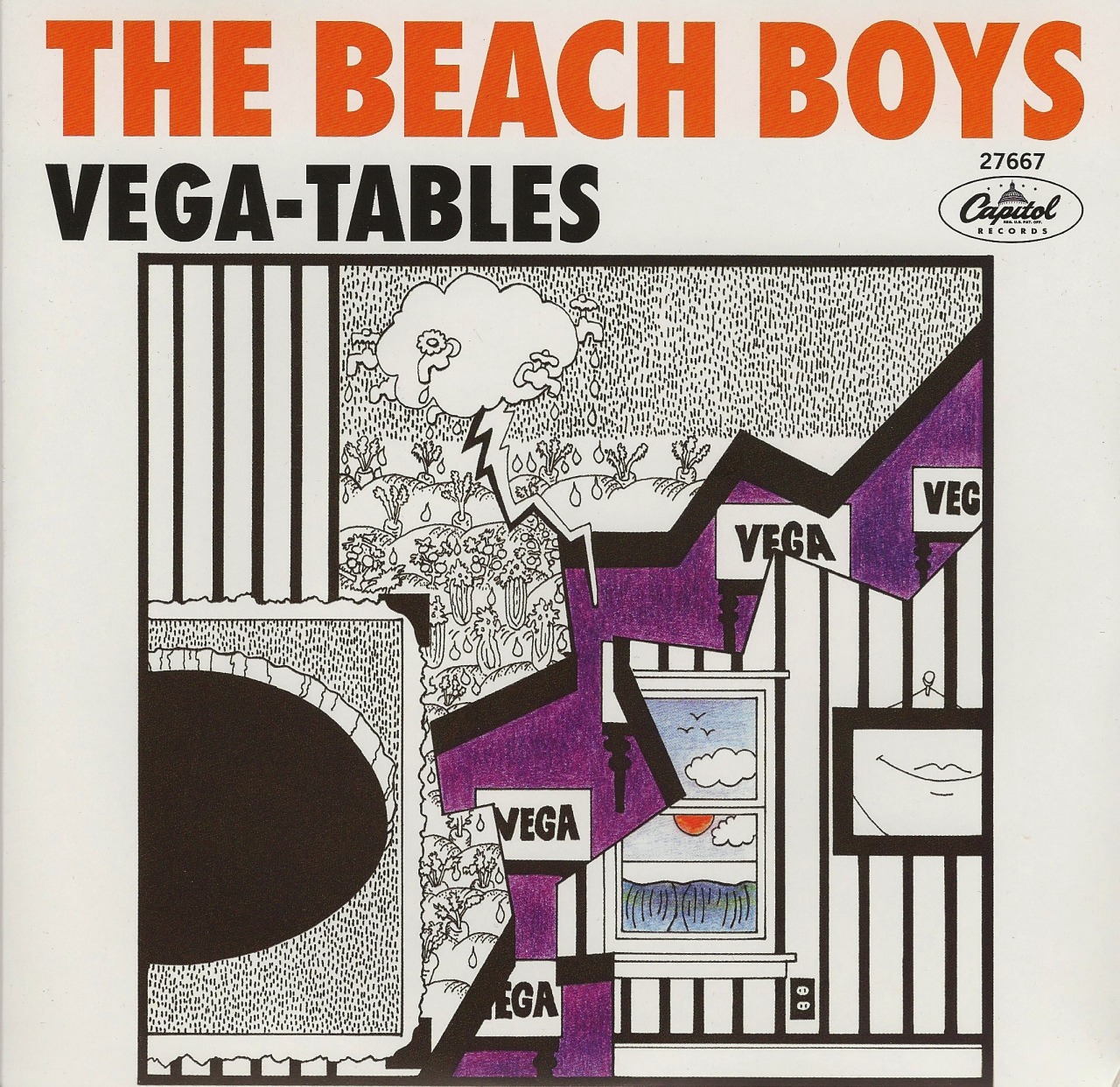

- The Beach Boys, The SMiLE Sessions: vinyl excerpts (Capitol, 2011)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2133482-1343184756-9314.jpeg.jpg)

- Horace Silver, Re-Entry (32 Jazz 1955, 1956)

- Zoot Sims in Paris (Vogue, 1950, 1953)

- Bill Frisell, Nashville (Nonesuch, 1997)

- Nara Leão, Pure Bossa Nova: A View on the Music of Nara Leão (Verve/ Phillips, 1967, 1971, 1984)

- Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers Live! (Everest, 1968)

![Art Blakey and the "Jazz Messengers": Live [ LP Vinyl ] - Amazon.com Music](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51QjUh1hTyL.jpg)

NEXT: Smiley Smile

No comments:

Post a Comment