Bud Powell was probably my first serious interest in jazz, from undergraduate days on. I met Jackie McLean in 1976 in his dressing room at Joe Segal's Jazz Medium on Rush Street. This was during the intermission after the first set, and Jackie was still practicing a particularly difficult passage on his horn, "trying to find out where it turns at." I knew of his relationship to Bud by reading the chapter devoted to McLean in A. B. Spellman's Black Music: Four Lives (Schocken Books, 1970) hat Jackie had know Bud Powell closely and over a long period of time.

|

| Alfred Lion with Bud Powell and family |

What follows of our conversation has been edited into a monologue.

I knew Bud Powell very well from about 1947 until he died in 1966. I was closest to him between 1947 and 1949. After that time I just knew Bud intermittently through out the years.

If anything, he was very aware of the exploitation that was happening to him, and preparing me for a life in music and for the exploitation ahead, which I didn't know anything about. I was nineteen at the time. Bud told me about the things that were happening to him in the business, about record company ripoffs, club owner ripoffs, the whole thing.

He was my teacher, and he helped me at a time when I needed help. When I came to him, I had only been playing about a year and a half, but by the time I had played four or five years I was working with Miles [Davis]. That can give you an idea of the kind of inspiration he gave me. He wasn't the kind of teacher where you go into a studio, and here's your lesson for today. I just used to go down to his house on weekends. Sometimes he would play with me, and sometimes he wouldn't. Sometimes he would go to the piano and invite me to play, and sometimes he would just go and play alone. Sometimes he would talk. I look at the time I spent with Bud as a whole studdy in music which I was fortunate enough to get.

At the time I first met him, Bud was just coming home from the hospital on weekend leaves. He used to ask me sometimes who Sonny Stitt was, or to tell him about Charlie Parker again, because they had given him shock treatments and he had forgotten things. I would sit down and talk to him, but I was really aghast, because I didn't realize at that time what could happen in those institutions, how men could play with other men's minds. Whatever the reason, the most horrible thing they did to Bud in the hospital, he revealed to me later, was that they didn't know he played the piano at first. One day he was in the solarium, and he went to the piano and started playing. And they immediately got the bright idea to give him shock treatments, and then send him to the piano to see what he could do. These are some of the things he went through.

Cootie Williams and Bud Powell duet on "Echoes of Harlem"

Bud was a very beautiful person. He was in a state of grace, all the time. As far as his playing is concerned, I can only listen to the records he made before I met him and the ones he made during the time I knew him. The shock treatments might have had an effect later on. I don't know that much about the brain and how electricity affects it. But he did tell me that such things happened to him on a couple of occasions.

He used drugs sporadically, from time to time, but he wasn't an addict. I read that he had been hit in the head by the police in Philadelphia, and that was the beginning of his having trouble with his head. I used to take him to jobs and bring him back. As I was a friend of the family, his mother would send me out with Bud on jobs. I would taker him to jobs and bring him back. He had to be taken to jobs in '47 and '48, and he was taken to jobs until he died. If he would go somewhere by himself and stop for a drink, that'd be it. He would've never arrived for a job. Anything could have happened to him.

Bud was a very beautiful person. He was in a state of grace, all the time. As far as his playing is concerned, I can only listen to the records he made before I met him and the ones he made during the time I knew him. The shock treatments might have had an effect later on. I don't know that much about the brain and how electricity affects it. But he did tell me that such things happened to him on a couple of occasions.

I met him in Europe in '61. I think that Bud had gone over there with a concert tour or something and had just remained. I don't think it was an independent decision on his part: "I think I want to go to Europe." I don't think he thought like that. In that time, the European scene was clubs. I worked on the Left Banque in a club called Le Chat Qui Peche, and Bud was working at the Blue Note on the Right Banque. I used to go back to my jobs after taking him home, and sometimes I would take him to work. I( was really around him quite a bit during that time. That was a strange reunion, because I hadn't seen him in many years. He was on the stand, and when he stood up to come off he looked at me, and I could see by the expression on his face that he recognized me. And I was very pleased by this, because I loved Bud very much.

It's very difficult for me to describe a genius, very hard for me to find words. I think the best way I can describe Bud is by saying he was in a state of grace. Sometimes he was very childlike, at other times very strong, and always very sensitive to every thing around him. I think the person he loved most among musicians was Monk, because I would go down to his house and see Monk there. Monk might come in on a Friday or Monday, and I'd come back on Wednesday and they'd still be there. Bud idolized Monk. I think that Bud was a true interpreter of Monk's music, as a piano player. He interpreted Monk's music probably the way Monk envisioned a piano interpretation of his music, other than his own.

Bud was a genius and totally out front at all times, speaking exactly what he felt at all times, reacted immediately to life as it affected him. If you did something cruel, he would respond in a very hurt way. If you did something beautiful, he would react in that way. It was just spontaneous. I don't think there was any foregoing thought about what he was going to say or do. He just did, as children do.

It's hard to say whether he felt any rivalry toward Bird. He loved Bird, but I think the only person I ever heard who played as much as Bird, or more than Bird, was Bud. Being on the bandstand together with Bud was probably a new thing for Bird to experience, because wherever Charlie Parker played, he was the most dominating musician, the most powerful interpreter of what he created. But Bud played as much or more than Bird, and I think sometimes Bird may have reacted to this. But Bud was never aware of it, I don't think.

I saw Bud's father on one occasion playing piano. He played stride piano very well and was also an electronics buff. He had all kinds of radios and equipment. I think Bud was a classically trained pianist, but I think his father also taught him things about jazz. I'm not fully aware of Bud's youth or musical background.

In closing, I was with Bud the last hours of his life when I went to the hospital to see him. He was alive, but in a coma. When I left and came back that same day, he was gone, so I think I was probably one of the last musicians around when he died. And on a few occasions, just months before he died, I went to Brooklyn and hung out with him some. I don't think it was his decision to come back to the United States. Buttercup, his wife, came back, and he came back with her. Perhaps it was some kind of proposal from some jazz impresario to bring Bud back and exploit him some more on the side, bleed him a little more. Some prick that owned a record company that had a lot of avant-garde music on it paid him fifty dollars to do a record date. And please, when write this down, spell "PRICK" in big, black letters, because you have to be a prick to do that to somebody like Bud. Nobody's ever grieved for Bud. Music is an intangible thing, a very beautiful thing that most people can relate to. But some people are so greedy, so involved with making money on anything, that they don't have any feeling for something as beautiful as music, and certainly not for any of the performers of it. One of the last things in his life that Bud did was to make a record date for-- I forget the name of the label. Some label that Ornette and Albert Ayler recorded for. Paid him fifty dollars for it!

His facility is artfully artless, like Ellington's.

- Bud Powell, Ups 'N Downs (Mainstream, 197?)

- J. J. Johnson, J.J. Johnson's Jazz Quintets (Savoy, 26 June, 1946)

- The Bebop Boys: three sessions in 1946 (Savoy, August 23, 1946); RCA Victor, September 5, 1946; Savoy, September 6, 1946)

|

| Benny Harris |

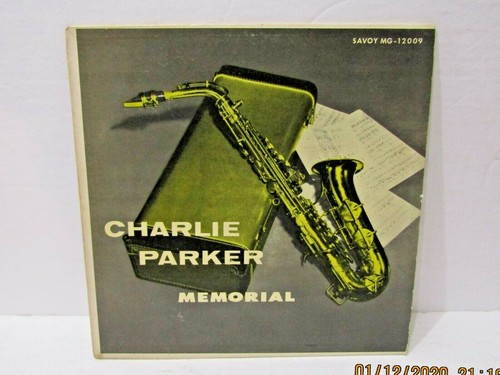

- Charlie Parker, The Charlie Parker Memorial Album, Volume 1 (Savoy, 1947)

|

| Norman Granz |

- Sonny Stitt/ Bud Powell Quartet (Prestige)

- Charlie Parker and the Stars of Modern Jazz at Carnegie Hall, Christmas 1949 (Jass CD)

- The Charlie Parker Quintet, Live, One Night in Birdland (Columbia, 1950)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4049098-1410795229-9809.jpeg.jpg)

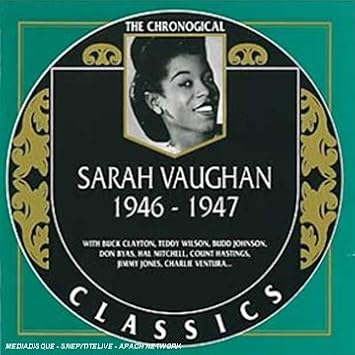

- Sarah Vaughan, 1946-1947

- Charlie Parker and the All Stars, Summit Meeting at Birdland

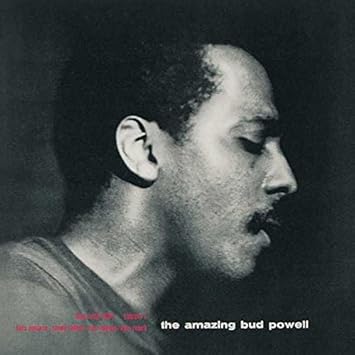

- The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 2 (Blue Note, May 1, 1951, August 14, 1953)

- Birdland, 1953

- Inner Fires (Electra Musician, April 5, 1953)

- The Quintet, Jazz at Massey Hall (Debut/ OJC, May 15, 1953)

- Bud Powell Trio, Jazz at Massey Hall, Volume Two (May 15, 1953)

- Bud Powell Trio (Roost, September, 1953)

- Bud Powell's Moods (Verve/ Norgran, June 2, 1954)

- Jazz Original (Verve, December 16, 1954; January 11 and 12, 1955, January 13, 1955)

- The Lonely One (Verve, April 25 and 27, 1955)

- Piano Interpretations by Bud Powell (Verve, April 25 and 27, 1955)

- Blues in the Closet (Verve, September 23, 1956)

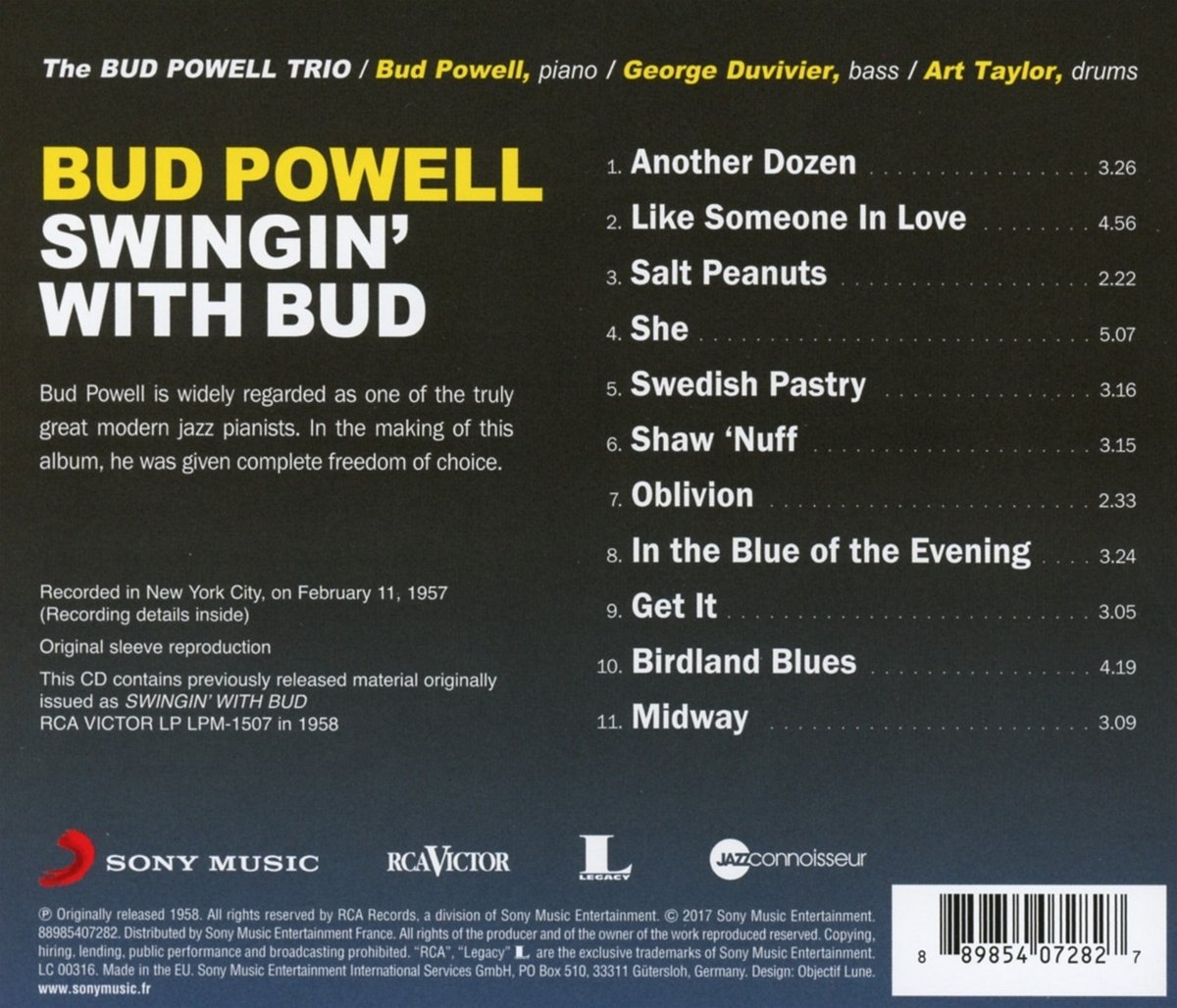

- Strictly Powell (RCA Victor, October 5, 1956)

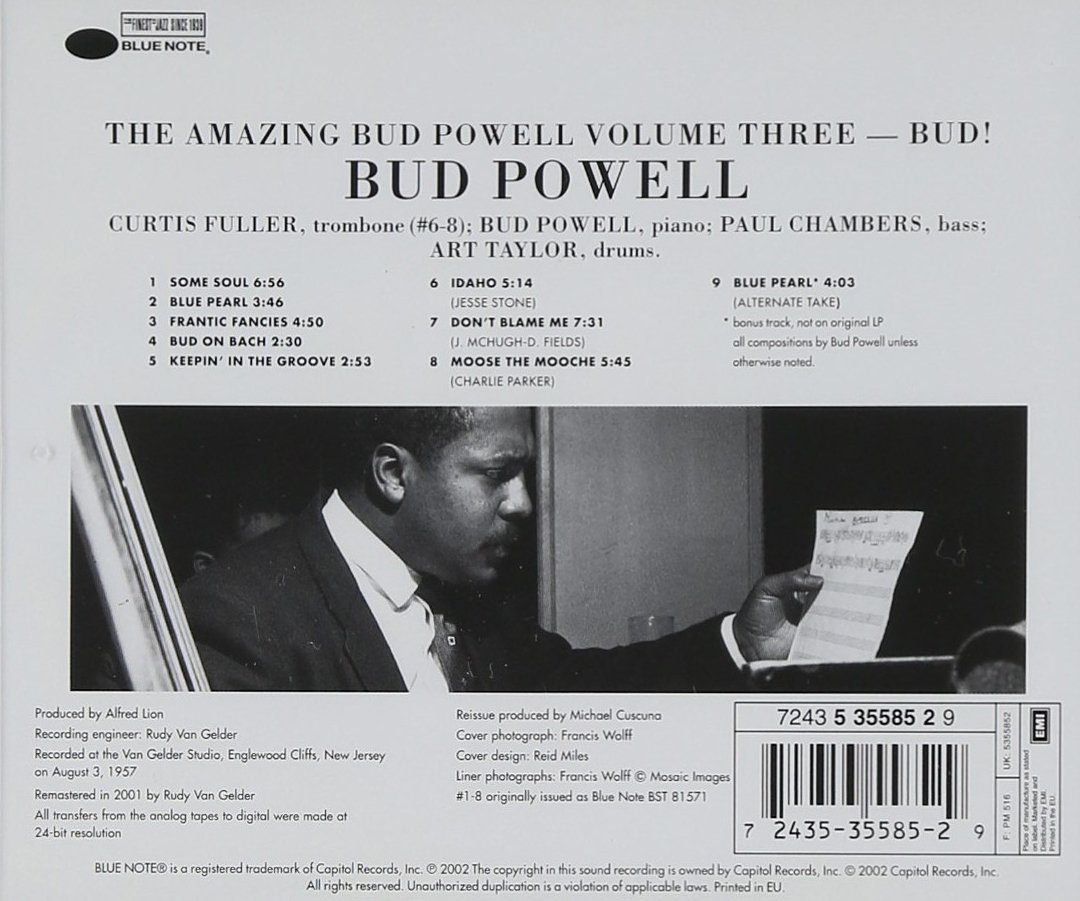

- Bud! The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 3 (Blue Note, August 3, 1957)

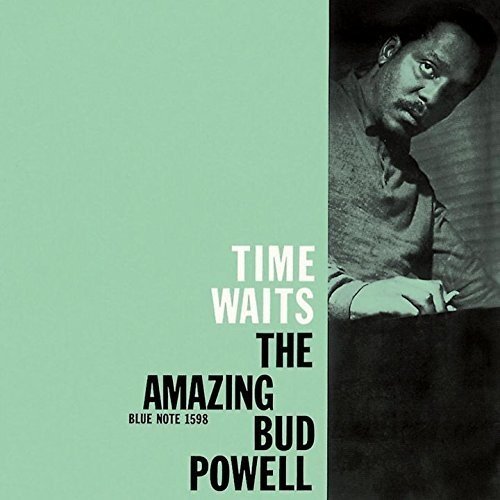

- Time Waits: The Amazing Bud Powell, Volume 4 (Blue Note, May 28, 1958)

- Bud Plays Bird (Roulette/ Blue Note, October 14 and December 2, 1957 and January 30, 1958)

- Time Waits: The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 4 (Blue Note, May 28, 1958)

- The Scene Changes: The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 5 (Blue Note, December 29, 1958)

![The Scene Changes (The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 5) [Vinyl]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/41glJIfueEL._SX355_.jpg)

- Ups 'N Downs, Mainstream, (1964-1965)

The most painful track of all is the solo "Round Midnight", which is probably from the Charlie Parker Memorial Concert in March of 1965. His guardian at the time, Bernard Stollman of ESP-Disk, swears that he destroyed the concert tapes, since he saw that Bud was in no shape to play, had fallen down, and was bleeding on the keyboard. Still, this track remains, showing Bud as a mere shadow of the keyboard technician he used to be, but as intense as ever. Compare this to the version of the same song he recorded with Bird and Fats Navarro in 1950, and you'll hear the tragedy of Bud Powell.

"Like Someone In Love" was Bud's mini-concerto late in his career, and this version still shows his early stride influences and some vestigial arpeggios.

The rest of the album sounds more together than most of what he recorded at Birdland in '64 or late in his stay in Paris. He keeps the groove burning on mid-tempo numbers, even though his once celebrated technique vanished after years of electro-shock therapy, tuberculosis, largactyl, and alcohol. No one knows who the drummer and bass player are, but they aid and abet wonderfully. They even navigate Coltrane's "Moment's Notice".

Bud Powell freaks know that ESP-Disk's Bernard Stollman tried to get Bud to record at Town Hall in May, '65, and again later in the year, and finally with Rashied Ali and Scotty Holt in Jan. '66 (Bud finally died at age 41 in July, '66). Nothing is known of those attempted sessions, or how this one came to be.

I hope to be able to play so passionately on my deathbed! I recommend this heartily only for other Bud Powell fans.

- The Complete Bud Powell on Verve (Verve 5-CD set, 1949-1956)

- The Complete Bud Powell Blue Note Recordings, 1949-1958 (Mosaic 5-LP set)

Bud Books

- Alan Groves and Alyn Shipton, The Glass Enclosure: The Life of Bud Powell (Bayou P, 1993) 144 pp

- Francis Paudras, Dance of the Infidels: A Portrait of Bud Powell (Editions l'Instant, France 1986; Da Capo P English translation, 1998) 353 pp

- Carl Smith, Bouncin' with Bud: All the Recordings of Bud Powell ( Biddle Publishing, 1997) 175 pp

- Peter Pullman, Wail: The Life of Bud Powell (Bop Changes, 2012) 415 pp

- Guthrie P. Ramsey, The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius, Jazz History, and the Challenge of Bebop (U California, 2013) 240 pp

- Reginald R. Robinson, Euphonic Sounds: Never Before Recorded Pieces by Louis Chauvin and Scott Joplin (Delmark, 1998)

- Miles Davis, Miles in the Sky (Columbia, 1968) needle-drop from the "Columbia Jazz Masterpieces" LP reissue.

- The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo (Columbia, 1968) 1997 EU reissue with 7 bonus track, plus a "hidden" track at the end.