III.

... [T]hey say it is the fatal destiny of that land, that no purposes whatsoever which are meant for her good will prosper or take good effect; which, whether it proceed from the very genius of the soil, or influence of the stars, or that Almighty God hath not yet appointed the time of her reformation, or that He reserveth her in the unquiet state still for some secret scourge, which shall by her come unto England, it is hard to be known, but yet much to be feared. 11

Historian Cyril Falls rightly emphasizes the qualitative disparity between the societies of England and Ireland in the sixteenth century, maintaining that there was "scarcely a point of contact" between them.12 Irish society at the time ranged from herdsmen in the remote "desert" interior of the country, through Irish freeholders and a few, generally hibernicized, Englishmen settled upon confiscated Irish estates, to the residents of the English Pale of villages and towns in garrisoned districts. The citizens of Dublin, in contrast to the great majority of the Irish, were greatly dependent on the English Crown, and the English-Irish nobility there were loyal to English law.

Spenser's commentary on the Irish countryside serves to illustrate Falls's observation on the sharp division between English and native Irish culture, for it proceeds entirely from the point of view of a Renaissance entrepreneur:

And sure it is yet a most beautiful and sweet country as any under heaven, being stored throughout with many goodly rivers, replenished with all sorts of fish most abundantly, sprinkled with many very sweet islands and goodly lakes, like little inland seas, that will carry even ships upon their waters, adorned with goodly woods, even fit for building of houses and ships, so commodiously, as that, if some princes in the world had them, they would soon hope to be lords of all the seas, and ere long of all the world. Also full of very good ports and havens opening upon England, as inviting us to come unto them, to see what excellent commodities that country can afford; besides the soil itself, most fertile, fit to yield all kind of fruit that shall be committed thereunto. 13

It may come somewhat of a surprise to find the father of English pastoral measuring the rural landscape in terms of its naked cash value, but the most consistent pattern of A View of the Present State of Ireland is to counterpose to the Irish pastoral economy the prospect of economic development and transformation to an English farm and mercantile system. Throughout his treatise, Spenser sets the English planter against the Irish herdsman and employs negative pastoral imagery for an explicitly anti-pastoral purpose, a point of view typical of the English generally and in the aspiring Spenser particularly. His argument contains a very learned (if sometimes mistaken) account of Irish legend, etymology, and history, but everything is set forth under the rubric of a Providential mingling of heathen and Christian nations.

The Irish revolt of Elizabethan times originated in the remote mountain wilderness areas of Munster, Connaught, Ulster, and the potions of Leinster that lay beyond the English Pale. The Norman Conquest had laid the basis of common law in both England and Ireland; its success in England had been due to the willingness of the English to accept authority under force of arms. But the Irish, "being a people very stubborn and untamed-- or if it were ever tamed, yet now lately having quite shaken off their yoke and broken the bonds of their obedience," were never "made to learn obedience unto laws, scarcely to know the name of law, but instead thereof have always preserved and kept their own law, which is the Brehon law..." 14

The English disliked and despised the native Irish law of the Brehons as much as they understood it," Falls elaborates. Brehon law was both civil and criminal. "The remarkable feature of the criminal side is that it was law virtually without sanctions, since there existed no machinery to enforce the decisions." Its civil aspect was mostly concerned with matters of succession and tenure. As " remarkably pure Aryan law, untouched by Roman," Brehon law was foredoomed by the Norman invasion, although traces of it would survive into the reign of James I. 15

A particular stumbling block to the English colonial administration, according to Spenser, was the fact that many Irish did not recognize the laws of primogeniture, the very keystone of the English patriarchal system but only one of several modes of inheritance prevalent in Ireland. The Irish tanist laws, for instance, directed inheritance to "not the eldest son, nor any of the children of the lord deceased, but the next to him of blood, that is the eldest and worthiest." 16 Spenser mocks taints ceremony as superstitious barbarism.

That the English, "at first as stout and warlike a people as ever the Irish... are now brought unto that civility, that no nation in the world excelleth them in all goodly conversation and all the studies of knowledge and humanity." 17 Spenser ascribes to the "the continual presence of their king" as a symbol of national unity, unlike the Irish, whom "no laws, no penalties, can restrain, but that they do, in the violence of that fury, tread down and trample under foot all, both divine and human, things, and the laws themselves they do specially rage at and rend in pieces, as most repugnant to their liberty and natural freedom, which in their madness they effect." 18

The life of the kern and gallowglas represents "the most barbarous and loathly conditions of any people, I think, under heaven... [They] oppress all men; they spoil as well the subject as the enemy; they steal, they are cruel and bloody, full common ravishers of women, and murderers of children." 19 The conflict between the barbarism of Ireland and the "civility" of England is often expressed in images of animals. "But what boots it to break a colt and to let him straight run loose at random?"

So were these people at first well handled, and wisely brought to acknowledge allegiance to the kings of England. But being straight left unto themselves and their own inordinate life and manners, they eftsoons forgot what before they were taught, and so soon as they were out of sight, by themselves shook off their bridles and began to colt anew, more licentiously than before. 20

With only a rudimentary level of tillage, sixteenth-century Ireland's principal source of wealth and major spoils of war derived from herding. In addition to cattle, there were also great herds of brood mares, swine, and goats, and sheep were plentiful in some districts. From their wild animal nature, it is but a short step for Spenser to condemn the entire range of Irish pastoral life, "to keep their cattle and to live themselves the most part of the year in boolies, pasturing upon the mountain and waste wild places, and removing still to fresh land as they have departures the former..., driving their cattle continually with them and feeding only on their milk and white meats."21 Spenser here refers to the Irish herdsman in Tyrone, living in "creet" communities and moving with their cattle from one pasture to another. The basic social unit of Irish herdsmen, the creaght, consisted of nomadic communities of cowherds and their families living in temporary sod and branch huts. Such a system provided military advantages to the Irish lords at war with the English, as Spenser was well aware. "Any outlaws or loose people," he complains, "are evermore succoured and find relief only in these boolies... whereas else they should be driven shortly to starve, or to come down to the towns to seek relief, where by one means or other they should soon be caught." 23 Equally obnoxious is the herdsman's customary wearing of a mantle and glib, a long lock of hair often used for purposes of disguise. In Spenser's reckoning, the glib is "a fit house for an outlaw, a meet bed for a rebel, and an apt cloak for a thief" and the mantle for women "a coverlet for her lewd exercise; and when she hath filled her vessel, under it she can hide both her burden and her blame." 24

From these and scores of other abuses in pastoral society, the English imperative at all times is to establish the husbandry of the plough over that of the herd, "for this keeping of cows is of itself a very idle life and a fit nursery for a thief." It is therefore "expedient to abridge their great custom of herding and augment their tillage and husbandry... for look into all countries that live in such sort by keeping of cattle and you shall find that they are both barbarous and uncivil, and also greatly given to war." 25 Prerequisite to the English objective of "civil society," the building of roads, bridges, forts, and fencing, and the establishment of secure market towns in the Irish interior, is the utter destruction of the pastoral economy and society.

As part of his purpose to deny such "customs of the Irish as seem offensive and repugnant to the good government of the realm," 26 Spenser launches a "scientific" attack on their primitive folk-belief. He refutes the basis in antiquity of Irish Gathelus mythology (viz. Gadelus, Gaedhal, whose Scythian father became son-in-law of the Pharaoh of Exodus. Named "lover of learning," Gaedhal founded the Irish tribe of Gaedels, or Gaels). 27 As if to frustrate the scientific historian, the obscurity of Irish origins is compounded by distortions by "bare traditions of time and remembrances of bards, which used to forge and falsify everything they list, to please or displease any man." 28

Spenser deems Irish verse to savor "of sweet wit and good invention, but skilled not of the goodly ornaments of poetry; yet were they sprinkled with some pretty flowers of their natural device which gave good grace and comeliness unto them."29 His main complaint is that the Irish bard's gifts are abused, an objection very much in keeping with the Puritan drift of Spenser's general argument that Ireland's vice is the perversion of English virtue. He pours contempt upon the bard, "whose profession is to set forth the praises or dispraises of men in their poems or rhymes; the which are had in so high regard and estimation amongst [the Irish], that none dare displease them for fear to run into reproach through their offence, and to be made infamous in the mouths of all men. For their verses are taken up with a general applause, and usually sung at all feasts and meetings."30

Sir Philip Sidney

This seems to be the very reasoning for the perfection of society expressed by Sidney in his Defense of Poesy, but Spenser explains that "these Irish bards are for the most part of another mind." Instead of worthy heroes, they celebrate "whomsoever the find to be the most licentious of life, most bold and lawless in his doing, most dangerous and desperate in all parts of disobedience and rebellious disposition... 31 The verse if the bard celebrating the legendary exploits of famous cattle-raiders causes the Irish youth to "waxeth most insolvent and half-mad for the love of himself and his own lewd deeds":

And as for words to set forth such lewdness, it is not hard for them to give a goodly and painted show thereunto, borrowed even from the praises which are proper to virtue itself. As of a most notorious thief and wicked outlaw... one of the bards in his praise will say that he was none of the idle milksops that was brought up by the fireside, but that most of his days he spent in arms and valiant enterprises; that he did never eat his meat before he had won it with his sword; that he lay not all night slugging in a cabin under his mantle, but used commonly to keep others waking to defend their lives; and did light his candle at the flames of their houses to lead him in the darkness; that the day was his night, and the night his day; that he loved not to be long wooing of wenches to yield to him, but where he came he took by force the spoil of other men's love, and left but lamentation to their loverss; that his music was not the harp or lays of love, but the cries of people and clashing of armour; and finally, that he died not bewailed of many, but made many wail when he died that dearly bought his death. 32

For Spenser, the Irish question, originally posed in terms of legal reform, finally emerges as the imperative to uproot the pastoral mode of existence and all its contemporary forms of expression. The Norman laws, he notes, took effect only among English settlers on estates abandoned by Irish early in the fourteenth century, and the Irish returned as vassals to Englishmen, whose own "will and commandment' became law to the Irish. 33 The Irish, however, turned from base humility to rebelliousness when the Wars of the Roses monopolized the resources of the English nobility during the following century. With the cessation of English civil strife and the establishment of a stable and vigorous national government, the opportunity was now at hand for the long-desired transformation of Ireland. The note of modernity in Spenser's prescription rings ominous and distinct: "When they are weary of wars and brought down to extreme wretchedness, then they creep a little perhaps, and sue for grace, till they have gotten new breath and recovered their strength again. So as it is in vain to speak of planting laws and plotting policy till they be altogether subdued." 34

IV.

Evil people, by good ordinances and government, may be made good, but the evil that is of evil itself will never become good. 35

There were two thousand English troops in Ireland at the time of Desmond's rebellion in the early 1580s. By the height of Tyrone's rebellion in the late 1590s, that number had swollen to fifteen thousand, and much of the countryside from Munster to Ulster had been largely depopulated, as Spenser himself bore witness:

notwithstanding that the same was a most rich and plentiful country, full of corn and cattle,... yet ere one year and a half they were brought to such wretchedness as that any stony heart would have rued the same. Out of every corner of the woods and glens they came creeping forth upon their hands, for their legs could not bear them; they looked like anatomies of death; the spake like ghosts crying out of their graves; they did eat the dead carrions, happy where they could find them; yea, and one another soon after, insomuch as the very carcasses they spared not to scrape out of their graves; and, if they found a plot of water-cresses or shamrocks, there they flocked as to a feast for the time, yet not able long to continue there withal; that in short space there were none almost left, and a most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man and beast. 36

One way to measure the historical distance between England and Ireland is by their contrasting modes of war narrative. To the Irish bards and chroniclers, wars were the occasion for the derring-do of individual champions and heroes. For the English, including Spenser, war was now a matter for the application of military science, theories to be buttressed by transport, logistics, and economics. From the start Spenser argues that a scorched-earth policy, had one been implemented even under Henry VIII, would have prevented the present Irish problem. 37 In the end, he insists upon the impossibility of a peaceful solution in Ireland, "for all these evils must first be cut away by a strong hand before any good can be planted." 38 He envisions the deployment of "such an army that should tread down all that stander before them on foot, and lay on the ground all the stiff-necked people of that land." 39

Spenser's plan calls for the mobilization of ten thousand infantry and one t thousand cavalry for a period of a year and a half, divided into garrisons strategically placed, the bulk of which are to be sent against Tyrone's strongholds in Ulster, with the strategy of restricting the enemy's creaght and starving him into submission, ideally during winter. After the end of a twenty-day ultimatum, the English war machine-- infantry, cavalry, and artillery-- would be unleashed.

To follow the Irish surrender, Spenser appends a detailed plan for a Pax Britannica, 40 a garrison state of 6000 troops to remain as a permanent force in Ireland. The plan provides general amnesty to civilians, with the Ulster rebels reduced to tenants on English estates. The administrative center would be moved from Dublin to Athy in the interior, while an influx of English and loyal Irish freeholders would remodel the Irish nobility by creating baronets and maintaining a pro-English majority in the Irish House of Lords, at the same time breaking the loyalty of the Irish commonality toward the old nobility. The regime would be supported by tithing the population. Spenser would disperse concentrations of native Irish among the English settlers and redivide the land according to the English system of wards and shires under the political control of a Lord President and council. Rather than continuing the long-standing policy of maintaining a "segregated" Pale, Spenser would increasingly mix the English with the Irish, with the aim of eventually anglicizing the country.

Spenser here reconstructs Ireland as utopia, uniting English and Irish, "to bring them to be one people and to put away the dislikeful conceit both of the one and the other." At the top of his social pyramid he places a platonic order of men of "special assurance," under the overall guidance of English aldermen 'of special regard, that may be a stay and pillar of all the borough under him." 41 At the base, he w ould appoint all non-freeholders "a certain trade of life, to which he shall find himself fittest and thought ablest, the which trade he shall be found to follow and live only thereupon," 42 Three social classes are to be established, what Spenser calls "manual trades" (peasantry), "mixed trades" (merchants), and intellectual trades" (nobility and gentry). All three classes are necessary, "but the realm of Ireland wanted the most principal of them, that is the intellectual: therefore in seeking to reform her state it is specially to be looked into."

ruins of Kilcolman Castle

Spenser, significantly, would revive

that old statute which was made in the reign of Edward the Fourth in England, by which it was commanded, that whereas all men then used to be called by the name of their septs, according to the several nations, and had no surnames at all, that from thenceforth each one should take upon himself a several surname, either of his trade and faculty, or of some quality of his body or mind, or of the place where he dwelt... And wherewithal would I also wish all of the O's and the Macs, which the head of septs have taken to their names, to be utterly forbidden and extinguished. 43

In short, Spenser would utterly destroy the old Irish nation and substitute a kingdom of reformed Englishmen. The political reform would begin with the viceroyalty itself. Spenser would retain the offices of Lord Deputy and Lord Justice, but the head of government, with absolute power and authority, should be "a Lord Lieutenant of some of the greatest personages in England." In an obvious reference to the popular Earl of Essex, he continues, "Such a one I could name, upon whom the eye of all England is fixed and our last hopes now rest." 44 Spenser's own last hopes for preferment were centered upon Essex, but again without result. Essex received just that appointment, but delayed until the end of 1598, by which time Spenser's fortunes in Ireland were in ruins.

A View directs its heaviest artillery against the administrations succeeding Lord Grey's, particularly the viceroyalties of Sir John Perrot (1584) and Sir William Fitzwilliam (1588). Spenser recalls the calumny of Lord Grey and insists that the lenient policies of Grey's successors had disrupted a strategy that would have brought the Irish rebellion to an end. He reserves his greatest scorn for the "degenerate" Englishmen in Ireland who have betrayed the civilizing mission of England.

"The chiefest abuses which are now in that realm are grown from the English," writes Spenser, "more lawless and licentious than the very wild Irish," especially in areas beyond the "reasonable civility" of the English Pale. The chief culprits are the English lords who combined with the Irish against the Crown to become "uncivil," "uncouth," and "strange," who speak the Irish language, intermarry with Irish women, and whose children are fostered by Irish culture. "The mind followers much the temperature of the body, and also the words are the image of the mind; so as they proceeding from the mind, the mind must needs be affected with the words; so that, the speech being Irish, the heart must needs be Irish..." 45

"And is it possible that an Englishman, brought up in such sweet civility as England affords, should find such liking in that barbarous rudeness that he should forget his own nature and forego his own nation?" Spenser asks. The state of Ireland, he concludes, has been undermined by English colonists who are "degenerated and grown mere Irish; yea, and more malicious to the English than the Irish themselves."46 He cites the evils of "rake-hell horse boys" ("only fit for the halter"), itinerant gamblers, jesters, ("notable rogues, and partakers not only of many stealths... but also privy to many traitorous practices and common carriers of news"): In short, "all this rabblement of runagates"47 c erupted by the laxity of colonial administration. Spenser demands an end to the private quartering of English troops in the countryside, with authority to confiscate foodstuffs and practice extortion upon the local peasantry, leading to a justifiable hatred of the royal soldiery. He condemns as well the English landlords' super exploitation of Irish peasantry via short-term tenancies and the institutions of coigny and livery, all of which served to shatter the peasant's loyalty to the system and made of him a poor subject.

In the words of a twentieth-century Irish rebel, James Connolly, the Irish peasant by the nineteenth century had been "reduced from the position of a free clansman owning his tribelands and controlling its administration in common with his fellows" to "a mere tenant-at-will subject to eviction, dishonour and outrage at the hands of an irresponsible private proprietor. Politically he was non-existent, legally he held no rights, intellectually he sank under the weight of his social abasement, and surrendered to the downward drag of his poverty. He had been conquered, and he suffered all the terrible consequences of defeat at the hands of a ruling class and nation who have always acted upon the old Roman maxim of 'Woe to the vanquished'... The seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries were, indeed, Via Dolorosa of the Irish race."48

In 1597 Spenser returned once more to Ireland, where he was appointed sheriff of Cork on September 30, 1598. October brought the onset of Tyrone's Munster uprisings, the burning of Kilcolman Castle, and the financial ruin of Spenser. On December 9 he was dispatched from Cork to London, where he died on January 16, 1599, bearing a proposal similar in content to A View. He is of course best remembered for his antique verse of knights errant and plaintive shepherds, but, in spite of the failure of his vision, he might be thought a significant voice of political modernity and an unrecognized prophet as well.

FOOTNOTES

2. See Annabel Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (Madison: U of Wisconsin Press, 1984), pp. 44, 47.

IN MY ROTATION

- Victor Feldman, Vic Feldman on Vibes (VSOP/ Mode, 1957)

- Don Cherry, Complete Communion (Blue Note, 1965)

- Zoot Sims, The Rare Albums Collection (Enlightenment, 1953-1963)

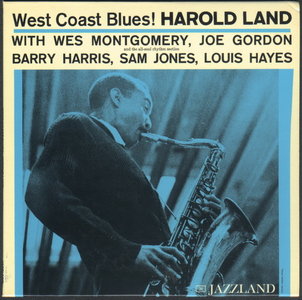

- Harold Land, The Early Albums (Enlightenment, 1953-19??)

- Jam Session (EmArcy, 1954)

- Dinah Washington, Dinah Jams (Emarcy, 1954)

- West Coast Blues! (Jazzland, 1960)

- The Beach Boys, Landlocked ("Brother" bootleg, 1971)

- The Beach Boys, Adult/Child ("Brother" bootleg, 1976)