SPENSER, PASTORAL AND IRELAND 1

I.

And if I waste, who will bewail my heavy chaunce?

And if I starve, who will record my cursed end?

And if I dye, who will saye: This was Immerito?

--Spenser to Gabriel Harvey, 1579

With a great deal on his mind, Edmund Spenser arrived in London late in 1595 from his adopted homeland, Ireland. If he carried with him high hopes of preferment, of patronage and influence, riding upon publication of the great quantity of verse he had composed, Spenser nonetheless must have crossed the Irish Sea in great perplexity of spirit over the recent course of events in the Irish countryside and the English court. His misgivings, obliquely set forth throughout most of his verse, were most clearly expressed in A View of the Present State of Ireland, which he either wrote or revised in England in 1596. But Spenser would not live to see his words in print, much less see them enacted into royal policy. A View was not registered with the Stationer's Company until April 13, 1598, for publication by Matthew Lownes, and even then, only "upon condicion that hee gett further aucthoritie before yt be prynted." Finally published in 1633 at Dublin by Sir James Ware, A View stands as the final word in Spenser's canon, yet it remains somewhat an orphan in modern scholarship, rarely invoked for the light it sheds on Spenser's more celebrated texts.

It is a critical commonplace that the fifth book of The Faerie Queene, among the other

manuscripts crossing the Irish Sea with Spenser in 1595, was written to honor the Irish campaigns of Arthur, Lord Grey de Wilton, and to shield his reputation against detractors at Queen Elizabeth's court; portions of the sixth book of Spenser's epic were also highly evocative of the author's experience in Ireland and at court. Such matters could be stated allegorically in The Faerie Queene but were too dangerous for publication in prose for nearly forty years. This fact not only calls attention to the Queen's tightening censorship upon historical works in the late 1590s, 2 but also highlights the emerging distinction between "literary" and "nonliterary" works and the operative rhetorical constraints within each category.

Eschewing nearly all the rhetorical dodges and obfuscations common in his literary productions, A View was a relatively straightforward exposition of the early stages of the native Irish rebellion against a corrupt English colonial administration and an unambiguous statement of Spenser's social and political views. If the "state of this misery and lamentable image of things" were to be "told and feelingly presented to her sacred Majesty, being by nature full of mercy and clemency," Spenser hoped, she would stop "the stream of such violences" and punish "the authors and counsellors of such bloody platforms." 3

The issue of Spenser's "authority," his political relationship to Elizabethan England's machinery of ideological repression, is here posed most sharply, but it had been problematic to his career ever since he assumed in his youth the vocation of author. The Shepheards Calender in 1579 had assumed an entire gamut of authorizing strategies, beginning with Spenser's verse prologue addressed to his noble patron, Sir Philip Sidney: "And if that envie barke at thee, / As sure it will, for succoure flee/ Under the shadow of his wing," Spenser advises his book. "And when thou art past jeopardee, / Come tell me what was sayd of me: / And I will send more after thee." The specter of envy and the perception of his own vulnerability evidently haunted Spenser, for his trepidations concerning the poem's reception were expressed in his October, 1579, correspondence with Gabriel Harvey, whose own signature had countenanced Spenser's anonymous debut as Immerito, "our new Poete." Already, however fortunate he was to enjoy the patronage of Leicester and Sidney, there is a sense of doomed aspiration in Spenser's ill-concealed disappointment at his audience with the Queen, apparently deferred: "Your desire to heare of my late being with hir Majestie must dye in it selfe." From the very outset of his career the new poet felt the venom of courtier cliques.

Gabriel Harvey

The same letter, interestingly, contains a very circumspect plea to Harvey that he reply "ere I goe, which will be (I hope, I feare, I thinke) the next weeke, if I can be dispatched of my Lorde." It seems reasonable to suppose that Spenser was at this time resigning himself to a career in Ireland, although almost a year would pass before he left England. Another letter to Harvey, dated April, 1580, from Westminster, refers evidently to the same travel plans, now postponed indefinitely: that olde greate matter still depending." Difficult as it is to define the origin or the circumstances of Spenser's decision to seek his fortune at the outposts of English civilization, they can probably be ascribed to his loyalty to the court factions Leicester-Sidney, whose extensive holdings in Ireland and influence upon the Queen's government had precipitated a military crisis that would dominate English politics in the late decades of the sixteenth century.

The young Spenser may have travelled to Ireland for a few months in Leicester's entourage as early as 1577 to witness the quelling of Desmond's Rebellion by the forces under Sir Philip Sidney. Though scholars remain in doubt concerning Spenser's actual presence, A View describes the execution of Murrogh O'Brien at Limerick in July, 1577, through the persona of an eyewitness:

If this brief tour of Ireland did indeed occupy Spenser during the year between his commencement as M.A. from Cambridge in 1576 and his employment by John Young, bishop of Rochester in 1578, its future significance loomed large. The following year, which saw the publication of The Shepheardes Calender and the first drafts of The Faerie Queene, constituted a key moment in Spenser's career as a would-be courtier and in the definition of his poetic vocation. By this time, it is clear that the poet was back in London, in the service of the Earl of Leicester and among the literary acquaintances of Leicester's nephew, Sir Philip Sidney. What remains unknown is the degree to which Spenser's hopes and visions were tied, even at this early date, to his adventures in the outlands. His very adoption of the pastoral mode and his creation of the Colin Clout persona-- a "natural" man in a social milieu reduced to essentials-- may well have been influenced by his anticipation of a successful career in Ireland.I saw an old woman, which was his foster-mother, take up his head whilst he was quartered and suck up all the blood that ran thereout, saying that the earth was not worthy to drink it, and therewith also steeped her face and breast and tore her hair, crying out and shrieking most terribly. 4

Spenser's Irish sojourn began in the relative security of the English Pale, which included the shires of Dublin, Meath, Westmeath, Kildare, and Louth. As secretary to the new Lord Deputy of Ireland, Lord Grey, Spenser arrived in Ireland in August, 1580. Though headquartered in Dublin throughout Grey's tenure, he frequently witnessed the devastation visited upon the Irish in campaigns beyond the Pale. Spenser apparently was present to observe the surrender and wholesale slaughter, by troops commanded by Sir Walter Raleigh, of a papal force of over six hundred men at Smerwick Bay in November, 1580. 5 Nothing scandalized Grey's reputation in London more than the apparent savagery of his treatment of these prisoners, and Spenser's View, sixteen years after the event, is at great pains to defend Grey's conduct. For years afterward, Grey was dogged by rumors that he had promised mercy in return for surrender, and now, wrote Spenser, "most untruly and maliciously do these evil tongues backbite and slander the sacred ashes of that most just and honourable personage, whose least virtue, of many excellent that abounded in his heroic spirit, they were never able to aspire unto." 6 This was the very Blatant Beast that had hounded Immerito in 1579 and that would figure so largely in the quest of Artegall in The Faerie Queene.

Arthur, Lord Grey de Wilton

In March, 1581, the year prior to Grey's recall, Spenser acquired clerkship for the faculties in the Dublin chancery, where he took advantage of his office by acquiring leases at modest rents on estates forfeited by Irish rebels. Among these was the lease to a house known as New Abbey in County Kildare, west of Dublin but still within the Pale, where he resided intermittently in 1583 and 1584. His interests the following year, however, shifted farther south to the Munster outlander, where he was appointed deputy to Ludovick Bryskett in the clerkship of the council of Munster. By 1586, Spenser held prebend of Effin in County Limerick and obtained perpetual lease of Kilcolman Castle in County Cork and the 3,028 acres surrounding, a compact block of land lying between the rivers Bregoge and Awbeg and the Ballythoura Hills. In 1588, resigning his clerkship, he occupied Kilcolman and continued over the years to acquire lands in a venture to settle families of English colonists in the Irish wilderness.

As Stephen Greenblatt observes, "For all Spenser's claims of relation to the noble Spensers of Wormleighton and Althorp, he remains a 'poor boy,' as he is designated in the Merchant Taylor's School and at Cambridge, until Ireland. It is there that he is transformed from the former denizen of East Smithfield to the 'undertaker'-- the grim pun unintended but profoundly appropriate-- of 3,028 acres of Munster land." 7 Spenser's career, Greenblatt adds, from 1582 on enhanced his social status (putting the "Gent." next to his name) at the expense of the social insecurity of his Irish predecessors, as he acquired "ruined abbeys, friaries expropriated by the crown, plow lands rendered vacant by famine and execution, property forfeited by those whom Spenser's superiors declared traitors." It therefore comes as no real surprise to find that Spenser "was involved intimately, on an almost daily basis, throughout the island, in the destruction of Hiberno-Norman civilization." 8

II.

Him first from court he to the cities coursed,And from the cities to the townes him prest,And from the townes into the countrie forsed,And from the country back to private farms he scorsed.From thence into the open fields he fled,Whereas the heardes were keeping of their neat,And shepheards singing to their flockes, that fed,Layes of sweete love and youthes delightfull hetat...--The Faerie Queene, VI.ix.3-4

By the end of his first decade as an Irish "planter," Spenser had formed new alliances to advance his cause in the English court, the most significant of which was with Sir Walter Raleigh, at Elizabieth's favor the proprietor of several large estates in Ireland. With the manuscripts of the first three books of his Faerie Queene and an assortment of Complaints, he accompanied Raleigh to England, his first return since arriving with Lord Grey in 1580, where he was at last introduced to Queen Elizabeth. Spenser's dedication of Colin Clout's Come Home Againe to Raleigh offers the new pastoral

... in part of paiment of the infinite debt in which I acknowledge my selfe bounden unto you, for your singular favors and sundrie good turnes showed to me at my late being in England, and with your good countenance protect against the malice of evill mouthes, which are alwaies wide open to carpe at and misconstrue my simple meaning.

If the "simple meaning" of Spenser's earlier pastoral was problematical, the model he was about to unveil in Colin Clout's Come Home Againe would reflect the new ambiguities of his present situation. Spenser's career, here at an important crossroad, probably lost more than it gained under the countenance of Raleigh, as it had earlier under that of Sidney and as it would again under the ill-fated Essex regime. Hence Spenser's stay in England in 1589-90 deepened the question of his social standing rather than clarifying it. While gaining the royal audience and assuring his poetic reputation by the publication of some of his most important works, Spenser also succeeded in arousing his enemies at court, particularly Burghley, to close the door upon him. Spenser returned to Ireland in 1591 with a small annual pension, rather than a hoped-for court sinecure, as the result of many months' machinations in London.

Accordingly, there were drastic changes in Spenser's pastoral mode. The Colin Clout character, in particular, underwent a transformation. Rather than reflecting, sometimes ironically, the natural landscape, Colin will now transform nature to glorify Cynthia. From a more-or-less coequal stature with other pastoral characters (Piers, Cuddy, Hobbinol, etc.) in The Shepheardes Calender, Colin now assumes the role of principal player among a chorus of pupils, rather than peers. (Indeed, the comic naivety of these characters often renders them childlike, reforming the pastoral community into a family under the fatherhood of Colin Clout, sharply differentiated by virtue of his superior knowledge of the world brought back from Cynthia's court.) Instead of the non-specific pastoral settings of the Calender, Colin will now inhabit a landscape explicitly Irish and invite identifiable Irish folklore (e.g., the tale of Father Mole) into his narrative. Perhaps most significant, the encomia to Cynthia and her court take on the tone of satire, however muted for the sake of prudence. Clearly, like Virgil in earlier times, Spenser had come to feel that the conventions of pastoral poetry could no longer serve his purpose.

The later books of The Faerie Queene likewise serve to emphasize the insufficiency of such "simple" pastoral forms as had been employed in The Shepheardes Calender. In Book V, Artegal emerges victorious in combat over the ambitious tyrant Grantorto and rescued from his grasp the lady Irena (i.e., Ireland), only to fall victim to the attacks of the hags Envie and Detraction, who set upon him with their monster, the Blatant Beast. Book VI proceeds as a continuation of the tale, as Calidore, the champion of courtesy, sets forth to destroy the Blatant Beast. The standard glosses of The Faerie Queene identify Calidore as Sir Philip Sidney and Pastorella as Sidney's wife, Frances Walsingham, later Lady Essex, with Meliboe as Sir Francis Walsingham, father-in-law of Sidney, Colin Clout as Spenser himself, his "lass" Elizabeth Boyle, and the "mighty pere" (canto xli) as Lord Burghley. However, it is difficult to square such a catalogue with the point Spenser seems to be establishing early on, namely that the Pastorella episode represents Calidore's distraction from his noble quest.

The travels of Calidore from court to cities, towns, country, private farms, and finally the pastoral land of open fields and herds parallel Spenser's own career. Among the shepherds Calidore discovers the aged Merliboe and his adopted daughter Pastorella, to whom he devotes his life. Winning Pastorella's love, he is lulled by his carefree life as a shepherd and soon rejects his own "idle hopes' as a courtier along with his faith in his original mission.

The charming pastoral world, however, is soon invaded by the Brigants, "A lawless people... / That never usde to live by plough or spade / But fed on spoile and booty, which they made / Upon their neighbors" (canto x, 39), and Meliboe and all his people are captured and taken to an ominous island in the wilderness to be sold into slavery. In the meantime, the wandering Calidore has fallen under the spell of Mt. Acidale, an idealized pastoral space, where Spenser creates a pastoral encomium very much patterned after that in his April eclogue or his homage to Cynthia in Colin Clouts Come Home Againe. Whan Calidore attempts to enter the magical space, however, the scene vanishes and only the lowly shepherd Colin Clout remains, "who for fell despight / Of that displeasure, broke his bag-pipe quight" (canto x, 18). Calidore, as if retreating from a pleasant pastoral delusion to historical reality, returns to find Meliboe murdered by the Bigants and Pastorella buried under a mountain of corpses. Before he can resume his quest after the Blatant Beast, he must free Pastorella from the grasp of the "uncivilized" Brigants.

The would-be courier's poetic glimpses of a "higher reality" may serve the cause of his own purification, but they cannot be communicated to a world gone awry. In the end, Calidore will fail in his quest, as the Blatant Beast, making scholars and poets, its special victims, continues to exude "civility":

... Ne sparest he most learned wits to rate,Ne swarth he the gentle poets rime.

***

Ne may this homely verse, of many meanest,Hope to escape his venomous despite,More than my former writs all were they cleanseFrom blamefull blot, and free from all that wite,With which some wicked tongues did it backbite,And bring into a mighty peres displeasure,That never deserved to endite.Therefore, do you my rimes, keep better measure,And seeke to please, that now is counted wisemen threasure.(canto xii, 40-410)

Recent scholars 9 have discovered in pastoral poetry the obscure outline of an England quite antithetical to the superficially pleasant and uncomplicated otium of Colin Clout and his classical models. Hidden behind the pastoral is the real world turned on its head: the social relations of colonialism and the modern totalitarian state. To accompany this interest in the correspondences between pastoral's protocols and those imposed by Tudor society, more attention must be directed to the fact that Elizabethan England was consumed by a seemingly endless colonial war in Ireland. It is especially curious that Spenser's Irish career, which subsumed nearly his entire output as a poet, has not been more thoughtfully and systematically used to guide an inquiry into his texts.

By placing pastoral within the context of an allegorical romance, as in these episodes with Mt. Acidale at their center, Spenser seems to be taking still another step along the route indicated by the significant changes in pastoral decorum introduced in Colin Clout's Come Home Againe. Clearly, Mt. Acidale represented for Spenser some sort of aesthetic crossroads, and the temptation is strong for us to read into it an attitude of pessimism and dejection, of disengagement and withdrawal. David Miller, for instance, in "Spenser's Vocation, Spenser's Career" argues that "the central premise of his idealized vocation, the humanist faith in literature as a mode of persuasion, is repeatedly questioned" and finds in Spenser's late work "signs of withdrawal, finally from direct engagement with the historical world."10 In the Mt. Acidale sequence and in the Mutabilitie Cantos we may well discover Spencer's "questioning of his own poetics," but with knowledge of his valedictory View of the State of Ireland, some two hundred pages of persuasive discourse, we simply cannot speak of any lessening of Spenser's desire to engage the historical world or to take his place in public debate. Indeed, A View was written by a man whose heart burned more fiercely than ever to move the lever of history.

That Spenser was aware of the hazards and distinctions between literary and nonliterary genres is made evident in his borrowing of literary devices in the service of a didactic, nonliterary project. The narration of A View is cast in the form of Socratic dialogue between two fictional personae, reminiscent of many of the eclogues in The Shepheardes Calender. The first, Eudoxis, seems to be a somewhat naive Englishman at home, while the other, Ireneus, appears in the guise of a sophisticated English sojourner in Ireland, expert in its customs, language, and history. Ireneus is commonly taken to be Spenser's mouthpiece (his name understood to mean Ireland itself). The mere adoption of fictional dialogue in the presentation of his argument can be seen both as a deliberately "literary" device to mask the author's own position from the censors and as a strategy to distance his reading audience from certain contemporary references in the debate over Ireland. In spite of such precautions, Spenser set out his text boldly according to the accepted rules of deliberative discourse and rhetorical disposition, elaborating a carefully constructed argument for the salvation of Ireland.

(TO BE CONTINUED)

IN MY ROTATION

- The Beach Boys, Good Timin': Live at Knebworth England, 1980 (Eagle, issued 2002)

The date was June 21, 1980. This outdoor concert, recording documents the circumstance of all five original Beach Boys-- the three Wilson brothers, Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Bruce Johnston-- being recorded on stage together for the last time. There was, of course, no way for the audience at Knebworth Park to know just how singular was the show they witnessed that night. The show was fine, but the experience of hearing it now is rather sad.

The concert was not well-attended: 43,000 fans in a 100,000-seat venue. Acts preceding the Beach Boys included Blues Band, Lindesfarne, Santana, Elkie Brooks, and Mike Oldfield. The weather, unfortunately, was cold and wet. Supporting musicians were Ed Carter on guitar, Joe Chemay on bass and backing vocals, Bobby Figueroa on drums, percussion and backing vocals, and Mike Meros on keyboards.

As for the setlist, only three of the songs were from the Beach Boys' current album, Keepin' the Summer Alive, in effect making their show an oldies jukebox. But they were still a potent live act.

This CD is also available with a DVD documenting the entire concert.

- The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Are You Experienced? (Reprise, 1967)

I recently nabbed a used copy of this extraordinary recording, the 2010 Legacy edition including a DVD bonus disc, at the 2nd&Charles store in Highland, Indiana. It is hard to overstate the impact this record had, and continues to exert, on pop music, with its guitar licks, thundering rhythms, musical electronic feedback, and acid-soaked sensibility on full display. The individual tracks are of such consistent quality that it's impossible to single out a handful that are particularly outstanding. Certainly the album is among the very best to come out of the 1960s, an especially fertile decade for music.

Lightly and politely

- Miles Davis , The Lost Quintet( Sleepy Night, 1969)

I took the trouble to compare these concert selections to the original studio versions, on Bitches Brew, The Sorcerer, and the two-LP compilation Directions. There was obviously a difference between this quintet and aggregations more than twice its size, but more importantly the studio recordings of Miles Davis were in the late sixties largely in the hands of producer Teo Macero: like rock music before it, jazz performance took a back seat to record production, and it was Macero who organized and spliced together scores of snippets from the band's studio rehearsals.

- Bob Dylan, Rough and Rowdy Ways (Columbia, 2020)

(First of a series of burns provided by BLB) I like this album a lot, more than most of Dylan's work this late in his career. Dylan's always been a word man, more than a music man, and he delivers memorable words here. The crown jewel is the sixteen-minute "Murder Most Foul," reflecting the JFK assassination, the way the world reacted to it, and Bob's own place in it.

"I Contain Multitudes," "Goodbye Jimmy Reed," "Crossing the Rubicon"... All memorable, all invite another listening.

The tunes are about what you'd expect on a Dylan album, rootsy and bluesy.

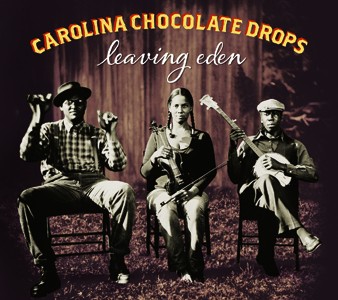

- The Carolina Chocolate Drops, Genuine Negro Jig (Nonesuch, 2009)

- ---------, Leaving Eden (Nonesuch, 2011)

Both discs provide a delightful immersion in bluegrass music. These musicians, all African American, serve to remind how much of this sort of music, and country music generally, has been a melding of styles all along. All play multiple instruments and sing stirring vocals.

Z

- Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane, At Carnegie Hall (Blue Note, 1957/ 200? LOC)

I hadn't listened to this disc, so I'd forgotten how good, how historic it really is. This is the same quartet who had earlier recorded for Riverside, but the month of working together steadily make these the far superior recordings.

SAD NEWS: NO MORE CAR CLUB

THE MARCH OF SCIENCE

Yes, its true: the 2005 Hyundai Elantra has shed its mortal coil. I bought a used 2019 Accent, only to discover, to my horror, it had no CD player. Apparently, this has been true for all new cars for quite some time. The upshot is that I will no longer be driving with 100 discs at my disposal; now I'm trying desperately to receive WDCB, apparently the Chicago area's only jazz radio station.

The music is fine, but my car radio picks it up only intermittently. There's a classical station whose broadcast often creep over the line to crowd out my jazz. Even so, I'd like the option of making my own music selections when I choose.

Good thing 'DCB isn't competing with a hip-hop station, of which there are far too many.

NEXT: Spenser, Part 2