MINSTRELSY AS RHEORICAL SITUATION

"Entertainment," particularly the American mass entertainment industry, has rarely been considered a field ripe for rhetorical analysis. If, however, there is a sense in which all art is propaganda, the various forms of mass commercial entertainment ought to provide a veritable blueprint of the means by which mass opinion is molded and influenced. By way of illustration, I wish to investigate the typical rhetorical features of the industry's great forebear, the American minstrel show, as it existed from the mid-1840s into the early years of the Twentieth Century.

One knotty problem to be addressed at the outset is that of exigence, without which a rhetorical situation cannot exist. Audiences, as a rule, do not patronize the entertainment media to be instructed or persuaded, as we usually understand these terms; they do so to be "entertained," for the sake of pleasure. Yet instruction and persuasion, as I will try to show, are very much built into the structure of entertainment, hidden, as it were, behind the laughter and sentiment of performance. In the case of the American minstrel show, as one scholar has noted:

By addressing themselves to race in the decades when white Americans had to come to grips with what the position of blacks would be in America, while at the same time producing captivating, unique entertainment, blackface performers quickly established the minstrel show as a national institution, one that more than any other of its time was truly shaped by and for the masses of average Americans. (Toll 26)

The exigence at issue, in fact, was nothing less than the future relationship between the white and black races in America. Although minstrel shows never posed this question explicitly, it was nonetheless imbedded within the reciprocal relationship between minstrel entertainers and their mass audience. Upon this foundation, we can draw some rhetorical generalizations about the genre and its descendants in American popular culture.

The mass entertainment market in America was in its formative stages in the years following the War of 1812. Even in its earliest years, it showed signs of an incipient bifurcation into highbrow and lowbrow cultures. The cultured elite, with their Shakespearean theaters, symphony orchestras, and ballet and opera companies, were content to ape European fashions. The growing mass audience in the cities reacted with scorn, and sometimes with violence, to such fare and demanded dramatic heroes of their own in melodrama, variety shows, the circus, and minstrelsy.

The existence of blackface entertainment on the American stage has been documented to Independence, and it achieved popularity well before the advent of the standard minstrel format. Until 1812, Negro characters were "either comic buffoons or romanticized noble savages" (Toll 26), but in the following decades they began to resemble one of the prototypical American Everyman characters, that of the bragging, wisecracking backwoodsman best exemplified by the legend of Davy Crocket. "Ethiopean Delineators" (as white actors in blackface came to bill themselves) appeared in the 1820s as solo acts. To audiences in Northern cities, most of whom had never seen a black person, they were taken to be authentic, faithful interpreters of Negro humor, song, and dance. Although there was sometimes some truth to the claim of authenticity, if only in a highly distorted amalgamation of African American folk materials, the "Negro" songs they sang were usually Irish or English folk or popular melodies garbed in dialect.

By the early 1840s, troupes of two and three blackface performers were entertaining New York audiences comprised of all social classes in American society, from the elite in their plush boxes to the poor in their faraway gallery. It was nascent Middle America in the pit area, however, to whom blackface entertainers learned to address themselves. The basic features of the American minstrel show, form and content, were "hammered out in the interaction between performers and the vocal audiences they sought only to please" (Toll 25). In February, 1843, the Bowery Amphitheatre debut of the (fictitiously named) Virginia Minstrels, whose professed aim was to portray the oddities, peculiarities, eccentricities, and comicalities of that "Sable Genus of Humanity," established a format that was to dominate American entertainment for half a century. By the following year, the Virginia Minstrels undertook a European tour and another troupe, the Ethiopian Serenaders, entertained at the White House, as minstrels would continue to perform there under the administrations of Tyler, Polk, Fillmore, and Pierce. The two decades prior to the Civil War saw an enormous proliferation of professional and amateur minstrel troupes, mostly local performers in the larger Northern cities, where they often enjoyed decade-long runs in theaters and regional circuits to small towns above the Mason-Dixon Line. By the mid-1840s, the ideal minstrel blend had been achieved, a balance of earthy comedy and robust music (the Virginia Minstrel style) with sentimental escapism (the Stephen Foster style).

To understand the rhetorical features of the minstrel show, it is perhaps best to begin with a discussion of its rhetors. interlocutor and end men, the dual specialty roles which came to define the minstrel format. Although not the character who attracted minstrelsy's large public, the most crucial role rhetorically was that of the interlocutor, since part of his function was to evaluate audience response moment to moment and orchestrate the show to its particular taste. By a variety of means, the discourse between interlocutor and end men served to reassure the white urban audience of its "middle" social status.

With a precise if somewhat pompous command of the language, an extensive vocabulary, and a resonant voice, the interlocutor personified dignity, which made the raucous comedy of the end men even funnier. When the end men mocked his pomposity, audiences could indulge their anti-intellectualism and antielitism by laughing at him. But when he patiently corrected the ignorant comedians with their malaprop-laden dialects, audiences could feel superior to stupid "niggers" and laugh with him. (Toll 52-53)

Significantly, the interlocutor nearly always got the worst of these exchanges, yet he never lost his dignity. Nevertheless, the jokes were usually at his expense, as Paskman observes: "Whenever an end man scores a point, he is joined in boisterous laughter by his balancing colleague at the opposite end, and often by the entire troupe." (24-25) The same author perceives further that the "give-and-take between the centre and ends of the semicircle has in it the necessary element of contrast, which brings the minstrel show almost to the level of actual drama." (24)

Originally as performed by the Virginia Minstrels, the interlocutor was one of four roles known collectively as the "burnt cork circle," which occupied four chairs arranged in a semicircle. The end positions to [the interlocutor's] right and left were occupied by characters known, after the instruments they played, as Mr. Bones and Mr. Tambo, who wore "absurd and elaborate farce costumes" Paskman 89) and sometimes made special entrances with comic business. In the earliest days of minstrelsy, the middle chairs would seat a banjoist and a fiddler, but in the years to come the shows would become more elaborate, adding more instrumentation (horns, string bass, flutes, etc.), sitting chorus roles assigned to tenor, baritone, and bass voices, and doubling the number of end men. By the apogee of its popularity, minstrelsy would feature companies of up to forty in lavish, expensive productions.

The costumes , exaggerated make-up, and dialect of minstrel shows, before an audience that believed (or at least wanted to believe) in their authenticity, functioned in the same manner as the enthymeme and paradigm of Aristotle's rhetorical system. It may be useful, in fact, to borrow from film theory the term "icon," denoting the recurrent visual images that define the standard film genres. One genre theorist, Colin McArthur, cites a "continuity over several decades of patterns of visual imagery, of recurrent objects and figures in dynamic relationship" leading to genres as "profilmic arrangements of sign-events" taken up and transformed by cinema from cultural codes already in circulation (cited in Cook 60, 86). In like fashion, minstrelsy gathered up and projected on a national scale most of the stereotypes of blacks that have permeated American mass culture and popular consciousness to this day: in Donald Bogle's terminology, the Coon, the Tom, the tragic Mulatto, and the Mammy (the vicious black "Buck" character was not given mass expression until D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation arrived at the crest of national race hysteria in 1915. Minstrelsy's cardinal rule was never to present blacks as a threat to whites, but rather to assure whites that blacks were happiest in a position of servitude).

In the ten-year evolution of the standard minstrel text, the genre came to draw on a variety of sources, from both Afro- and Euro-American folk culture, and thoroughly amalgamated them into a mass, popular culture. Beyond this transmuted lexicon of folk sources, minstrelsy was built virtually from the ground up:

[Minstrelsy] had no characterization to develop, no musical score, no set speeches, no subsidiary dialogue-- indeed no fixed script at all. Each act-- song, dance, joke, or skit-- was a self-contained performance that strived to be a highlight of the show. This meant that minstrels could adapt to their specific audience while the show was in process (Toll 34).

The text of the minstrel show consisted of two rudimentary parts, the first of which "had a definite technique to which all minstrel men were unswervingly loyal, and which has been consistently observed throughout its history (Paskman 21). Typically the opening curtain would reveal the company of minstrels standing in position behind their chairs. The interlocutor, at exact center, would begin with a ceremonial "Gentlemen, be seated!" and then announce an instrumental overture. The interlocutor would then resume by establishing repartee with one of the end men: "Good evening, Mr. Bones." Then would ensue, in Paskman's description,

a running dialogue between the middle man... and the two end men... This dialogue was interrupted at regular intervals by set songs, ponderously and portentously announced by the Interlocutor, with the whole company frequently joining in the chorus. In fact, the whole machinery of jokes and pompous persiflage existed chiefly for the sake of introducing these set numbers (21).

The song material fell into two general categories, both of which have entered deeply into the consciousness of succeeding generations of Americans. First came exuberant, happy-go-lucky songs on the order of "Dixie" (originally "I Wish I Was in Dixie's Land," written by Dan Emmett of the original Virginia Minstrels in 1859), "Zip Coon" (a.k.a. "Turkey in the Straw"), "Clar de Kitchen," "Lucy Song," "Such a Gettin' Up Stairs," "Gumbo Chaff," "Sittin' on a Rail," and many others. The other category, greatly stimulated by the popular success of Negro Spirituals as performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, was comprised of sentimental ballads of contented Negroes on idealized, pastoral plantations. Between these songs would run a seemingly endless stream of jokes, based principally upon puns, malapropisms, conundrums, and physical humor.

The First Part of the minstrel show would generally end with a "walk-around" by the entire troupe, which rose

to a frenzied pandemonium of rhythmic sound. Bones and Tambo, leaning at an angle of forty-five degrees, and holding their noise makers high in the air, sustain the climax as long as body and soul can stand the strain. One final triumphant chord from the band, and the curtain drops on the First Part (Paskman 28)

While the stage was being set for the Second Part, individual members of the troupe would perform specialty acts in an "olio" that included burlesques and parodies of well-known dramatic scenes, buck and wing dancing, instrumental performers, and satirical "stump speeches." The olio counterpoised a sort of free fantasy to the rigid structure of the First Part. "Here technique is thrown to the winds, and formulas of every kind are forgotten (Paskman 83)."

The Second Part proper (often called the "afterpiece") sometimes presented a complete drama, either a wild farce or a tearful melodrama, as changing fashions and the social climate dictated. In both forms, the Second Part was often built upon a romantic triangle, with a featured female impersonator in the "nigger wench" role. In its heyday after the Civil War, minstrelsy thus seemed to be responding to a new exigency, the "woman question," again from a white male point of view.

The full impact of minstrelsy upon future popular entertainment genres lies beyond the scope of this paper. My emphasis upon its rhetorical function, however, entitles us to observe, along with Robert Toll, that minstrelsy was not only "the first indication of the powerful influence Afro-American culture would have on the performing arts in America," but also "the first example of the way American popular culture would exploit and manipulate Afro-Americans and their culture to please and benefit white Americans" (51). Because it was presented in the guise of entertainment, however, the implicit rhetoric of minstrelsy was seldom apparent to its nineteenth-century audiences, or even to its twentieth-century chroniclers. Writing in 1928, Paskman could still write longingly and unblushingly of the days when the "shuffling old darky" served for stage entertainment, and Doubleday could publish such commentary without fear of an outcry. So drastic a shift has our discourse on race taken that what was once acceptable, even "natural," stage entertainment can now appear only a barbaric vestige of a past most of us would rather forget.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mammies, Mulattoes, & Bucks. New York: Viking, 1973.

Cook, Pam, ed. The Cinema Book: A Complete Guide to Understanding the Movies. New York:

Pantheon, 1985.

Engel, Gary D. This Grotesque Essence: Plays from the American Minstrel Stage. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State UP, 1978.

The Entertainer: Everybody's Favorite Series No. 10. New York: Amsco Music Sales Co., ca. 1935.

Haverly, Jack. Negro Minstrels: A Complete Guide. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature House/

Gregg Press, 1969.

Paskman, Dailey. "Gentlemen, Be Seated!" A Parade of the American Minstrels. New York:

Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1976. Original publication: New York: Doubleday, 1928, with co-

author Sigmund Spaeth.

Roorbach, O. Minstrel Gags and End Men's Handbook. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature

House/ Gregg Press, 1969.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York:

Oxford UP, 1974.

Wittke, Carl. Tambo and Bones: A History of the American Minstrel Stage. New York: Greenwood

P, 1968.

Int. That was sensible. Well, what did you then, sir?

Bones. De fustest man dat cum along was a chap dat was a little de wuss for licker. "Bossy," says I, "we's bofe on us dead gone broke; gib us a lift." "I'll gib you a lift," says he, and wid dat he made a grab for me, but I up and tap him on de snoot and down he go like a log; got de deadfall on him, sure! "Spar' me," says he, I'se only a flat boatman." Den I histe him, and he go away quite sober. Den I skedaddled in a panic. When I had got out of sight, "Pete," says I, "we's in a corner now; money all gone, and no credit nudder.["] Just den we come to a broker's office. A bright idear struck me. I went in. "Do you give discount here?" says I. "Certainly," says he. "Well, den," says I, "just discount me a twenty." "All right," says he, "fork over. Where's your twenty?" "O," says I, "I'll gib dat to you after I've turned dis over." "Not on discound," says he, " and dis aint de place for your kind o' operations rudder. Just you take dis banjo and go out on de side walk and gib us a song and a broke down, and de banjo's yours and all you can make by it." Dat was enuff, so I took de banjo and I go out on de sidewalk and begin to play and caper; and pooty presently a crowd cum along, and I gub all de songs and jigs I was quainted did, and de money it come rollin' in by de handful, while Pete carried roun' de hat. When I'd 'bout got tired I start to go, but jus den a gemman come up and tap me on de shoulder. "You're my meat," says he. "I want a good jiggist for my minstrel show. State your price and come along;" and dat's de way I got into de burnt cork bisness.

Int. You were just then like a pugilist when he knocks his opponent out of time.

Bones. How's dat?

Int. You made a decided hit.

Bones. O, I become werry popular after dat and day engage me as todder end man at de show. and de oder todder end man was so jealous dat he gib me jaw and I hit him, and he challenge me; but, somehow, we both of us fought shy of each oder, and de papers got up a conundrum about it. Says one feller, says he, "Why am de projected 'fair of honor tween two well known burnt corkers in dis city like do predicament of a family dat finds it difficult to pay expenses?" And what do you tink de answer was? "'Cause it is hard to make both 'ends' meet."

APPENDIX C: "THE FIRST WHITE MAN"

One knotty problem to be addressed at the outset is that of exigence, without which a rhetorical situation cannot exist. Audiences, as a rule, do not patronize the entertainment media to be instructed or persuaded, as we usually understand these terms; they do so to be "entertained," for the sake of pleasure. Yet instruction and persuasion, as I will try to show, are very much built into the structure of entertainment, hidden, as it were, behind the laughter and sentiment of performance. In the case of the American minstrel show, as one scholar has noted:

By addressing themselves to race in the decades when white Americans had to come to grips with what the position of blacks would be in America, while at the same time producing captivating, unique entertainment, blackface performers quickly established the minstrel show as a national institution, one that more than any other of its time was truly shaped by and for the masses of average Americans. (Toll 26)

The exigence at issue, in fact, was nothing less than the future relationship between the white and black races in America. Although minstrel shows never posed this question explicitly, it was nonetheless imbedded within the reciprocal relationship between minstrel entertainers and their mass audience. Upon this foundation, we can draw some rhetorical generalizations about the genre and its descendants in American popular culture.

The mass entertainment market in America was in its formative stages in the years following the War of 1812. Even in its earliest years, it showed signs of an incipient bifurcation into highbrow and lowbrow cultures. The cultured elite, with their Shakespearean theaters, symphony orchestras, and ballet and opera companies, were content to ape European fashions. The growing mass audience in the cities reacted with scorn, and sometimes with violence, to such fare and demanded dramatic heroes of their own in melodrama, variety shows, the circus, and minstrelsy.

The existence of blackface entertainment on the American stage has been documented to Independence, and it achieved popularity well before the advent of the standard minstrel format. Until 1812, Negro characters were "either comic buffoons or romanticized noble savages" (Toll 26), but in the following decades they began to resemble one of the prototypical American Everyman characters, that of the bragging, wisecracking backwoodsman best exemplified by the legend of Davy Crocket. "Ethiopean Delineators" (as white actors in blackface came to bill themselves) appeared in the 1820s as solo acts. To audiences in Northern cities, most of whom had never seen a black person, they were taken to be authentic, faithful interpreters of Negro humor, song, and dance. Although there was sometimes some truth to the claim of authenticity, if only in a highly distorted amalgamation of African American folk materials, the "Negro" songs they sang were usually Irish or English folk or popular melodies garbed in dialect.

By the early 1840s, troupes of two and three blackface performers were entertaining New York audiences comprised of all social classes in American society, from the elite in their plush boxes to the poor in their faraway gallery. It was nascent Middle America in the pit area, however, to whom blackface entertainers learned to address themselves. The basic features of the American minstrel show, form and content, were "hammered out in the interaction between performers and the vocal audiences they sought only to please" (Toll 25). In February, 1843, the Bowery Amphitheatre debut of the (fictitiously named) Virginia Minstrels, whose professed aim was to portray the oddities, peculiarities, eccentricities, and comicalities of that "Sable Genus of Humanity," established a format that was to dominate American entertainment for half a century. By the following year, the Virginia Minstrels undertook a European tour and another troupe, the Ethiopian Serenaders, entertained at the White House, as minstrels would continue to perform there under the administrations of Tyler, Polk, Fillmore, and Pierce. The two decades prior to the Civil War saw an enormous proliferation of professional and amateur minstrel troupes, mostly local performers in the larger Northern cities, where they often enjoyed decade-long runs in theaters and regional circuits to small towns above the Mason-Dixon Line. By the mid-1840s, the ideal minstrel blend had been achieved, a balance of earthy comedy and robust music (the Virginia Minstrel style) with sentimental escapism (the Stephen Foster style).

To understand the rhetorical features of the minstrel show, it is perhaps best to begin with a discussion of its rhetors. interlocutor and end men, the dual specialty roles which came to define the minstrel format. Although not the character who attracted minstrelsy's large public, the most crucial role rhetorically was that of the interlocutor, since part of his function was to evaluate audience response moment to moment and orchestrate the show to its particular taste. By a variety of means, the discourse between interlocutor and end men served to reassure the white urban audience of its "middle" social status.

With a precise if somewhat pompous command of the language, an extensive vocabulary, and a resonant voice, the interlocutor personified dignity, which made the raucous comedy of the end men even funnier. When the end men mocked his pomposity, audiences could indulge their anti-intellectualism and antielitism by laughing at him. But when he patiently corrected the ignorant comedians with their malaprop-laden dialects, audiences could feel superior to stupid "niggers" and laugh with him. (Toll 52-53)

Significantly, the interlocutor nearly always got the worst of these exchanges, yet he never lost his dignity. Nevertheless, the jokes were usually at his expense, as Paskman observes: "Whenever an end man scores a point, he is joined in boisterous laughter by his balancing colleague at the opposite end, and often by the entire troupe." (24-25) The same author perceives further that the "give-and-take between the centre and ends of the semicircle has in it the necessary element of contrast, which brings the minstrel show almost to the level of actual drama." (24)

Originally as performed by the Virginia Minstrels, the interlocutor was one of four roles known collectively as the "burnt cork circle," which occupied four chairs arranged in a semicircle. The end positions to [the interlocutor's] right and left were occupied by characters known, after the instruments they played, as Mr. Bones and Mr. Tambo, who wore "absurd and elaborate farce costumes" Paskman 89) and sometimes made special entrances with comic business. In the earliest days of minstrelsy, the middle chairs would seat a banjoist and a fiddler, but in the years to come the shows would become more elaborate, adding more instrumentation (horns, string bass, flutes, etc.), sitting chorus roles assigned to tenor, baritone, and bass voices, and doubling the number of end men. By the apogee of its popularity, minstrelsy would feature companies of up to forty in lavish, expensive productions.

The costumes , exaggerated make-up, and dialect of minstrel shows, before an audience that believed (or at least wanted to believe) in their authenticity, functioned in the same manner as the enthymeme and paradigm of Aristotle's rhetorical system. It may be useful, in fact, to borrow from film theory the term "icon," denoting the recurrent visual images that define the standard film genres. One genre theorist, Colin McArthur, cites a "continuity over several decades of patterns of visual imagery, of recurrent objects and figures in dynamic relationship" leading to genres as "profilmic arrangements of sign-events" taken up and transformed by cinema from cultural codes already in circulation (cited in Cook 60, 86). In like fashion, minstrelsy gathered up and projected on a national scale most of the stereotypes of blacks that have permeated American mass culture and popular consciousness to this day: in Donald Bogle's terminology, the Coon, the Tom, the tragic Mulatto, and the Mammy (the vicious black "Buck" character was not given mass expression until D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation arrived at the crest of national race hysteria in 1915. Minstrelsy's cardinal rule was never to present blacks as a threat to whites, but rather to assure whites that blacks were happiest in a position of servitude).

In the ten-year evolution of the standard minstrel text, the genre came to draw on a variety of sources, from both Afro- and Euro-American folk culture, and thoroughly amalgamated them into a mass, popular culture. Beyond this transmuted lexicon of folk sources, minstrelsy was built virtually from the ground up:

[Minstrelsy] had no characterization to develop, no musical score, no set speeches, no subsidiary dialogue-- indeed no fixed script at all. Each act-- song, dance, joke, or skit-- was a self-contained performance that strived to be a highlight of the show. This meant that minstrels could adapt to their specific audience while the show was in process (Toll 34).

The text of the minstrel show consisted of two rudimentary parts, the first of which "had a definite technique to which all minstrel men were unswervingly loyal, and which has been consistently observed throughout its history (Paskman 21). Typically the opening curtain would reveal the company of minstrels standing in position behind their chairs. The interlocutor, at exact center, would begin with a ceremonial "Gentlemen, be seated!" and then announce an instrumental overture. The interlocutor would then resume by establishing repartee with one of the end men: "Good evening, Mr. Bones." Then would ensue, in Paskman's description,

a running dialogue between the middle man... and the two end men... This dialogue was interrupted at regular intervals by set songs, ponderously and portentously announced by the Interlocutor, with the whole company frequently joining in the chorus. In fact, the whole machinery of jokes and pompous persiflage existed chiefly for the sake of introducing these set numbers (21).

The song material fell into two general categories, both of which have entered deeply into the consciousness of succeeding generations of Americans. First came exuberant, happy-go-lucky songs on the order of "Dixie" (originally "I Wish I Was in Dixie's Land," written by Dan Emmett of the original Virginia Minstrels in 1859), "Zip Coon" (a.k.a. "Turkey in the Straw"), "Clar de Kitchen," "Lucy Song," "Such a Gettin' Up Stairs," "Gumbo Chaff," "Sittin' on a Rail," and many others. The other category, greatly stimulated by the popular success of Negro Spirituals as performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, was comprised of sentimental ballads of contented Negroes on idealized, pastoral plantations. Between these songs would run a seemingly endless stream of jokes, based principally upon puns, malapropisms, conundrums, and physical humor.

Judy Garland in Babes on Broadway (1941)

The First Part of the minstrel show would generally end with a "walk-around" by the entire troupe, which rose

to a frenzied pandemonium of rhythmic sound. Bones and Tambo, leaning at an angle of forty-five degrees, and holding their noise makers high in the air, sustain the climax as long as body and soul can stand the strain. One final triumphant chord from the band, and the curtain drops on the First Part (Paskman 28)

While the stage was being set for the Second Part, individual members of the troupe would perform specialty acts in an "olio" that included burlesques and parodies of well-known dramatic scenes, buck and wing dancing, instrumental performers, and satirical "stump speeches." The olio counterpoised a sort of free fantasy to the rigid structure of the First Part. "Here technique is thrown to the winds, and formulas of every kind are forgotten (Paskman 83)."

The Second Part proper (often called the "afterpiece") sometimes presented a complete drama, either a wild farce or a tearful melodrama, as changing fashions and the social climate dictated. In both forms, the Second Part was often built upon a romantic triangle, with a featured female impersonator in the "nigger wench" role. In its heyday after the Civil War, minstrelsy thus seemed to be responding to a new exigency, the "woman question," again from a white male point of view.

The full impact of minstrelsy upon future popular entertainment genres lies beyond the scope of this paper. My emphasis upon its rhetorical function, however, entitles us to observe, along with Robert Toll, that minstrelsy was not only "the first indication of the powerful influence Afro-American culture would have on the performing arts in America," but also "the first example of the way American popular culture would exploit and manipulate Afro-Americans and their culture to please and benefit white Americans" (51). Because it was presented in the guise of entertainment, however, the implicit rhetoric of minstrelsy was seldom apparent to its nineteenth-century audiences, or even to its twentieth-century chroniclers. Writing in 1928, Paskman could still write longingly and unblushingly of the days when the "shuffling old darky" served for stage entertainment, and Doubleday could publish such commentary without fear of an outcry. So drastic a shift has our discourse on race taken that what was once acceptable, even "natural," stage entertainment can now appear only a barbaric vestige of a past most of us would rather forget.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mammies, Mulattoes, & Bucks. New York: Viking, 1973.

Cook, Pam, ed. The Cinema Book: A Complete Guide to Understanding the Movies. New York:

Pantheon, 1985.

Engel, Gary D. This Grotesque Essence: Plays from the American Minstrel Stage. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State UP, 1978.

The Entertainer: Everybody's Favorite Series No. 10. New York: Amsco Music Sales Co., ca. 1935.

Haverly, Jack. Negro Minstrels: A Complete Guide. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature House/

Gregg Press, 1969.

Paskman, Dailey. "Gentlemen, Be Seated!" A Parade of the American Minstrels. New York:

Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1976. Original publication: New York: Doubleday, 1928, with co-

author Sigmund Spaeth.

Roorbach, O. Minstrel Gags and End Men's Handbook. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature

House/ Gregg Press, 1969.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York:

Oxford UP, 1974.

Wittke, Carl. Tambo and Bones: A History of the American Minstrel Stage. New York: Greenwood

P, 1968.

THREE MINSTREL PIECES IN SEARCH OF A RHETORICAL HEURISTIC

Perhaps nothing proves the usefulness of Edward P. J. Corbett's characterization of rhetorical criticism as a bridge between "inside" textual analysis and "outside" historical reality better than a study of American minstrelsy. While Corbett conceives rhetorical analysis proceeding outward from the text, however, it might be better in this case to insist upon a rhetorical "commutative principle" and also stress the priority of the diachronic material world over the static synchronicity of any given minstrel text. We must first realize that this bit of text represents the process, as well as the product, of countless thousands of interactive performances, changing constantly over a period of more than fifty years.

For this reason, the selections I append here, although they were chosen to reflect the triptych construction of standard minstrel performances, can not be considered "typical." Bits of gags, songs, and stage business performed by white "nigger minstrels" in blackface before a white audience at the Bowery Theatre in the 1840s may well have worked for quite different rhetorical ends than the same bits performed by black "colored minstrels" before a black audience in Alabama in the 1880s. We have to know context before we can handle text.

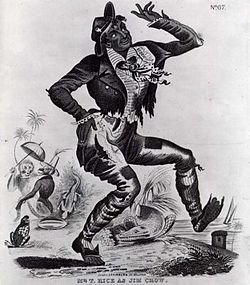

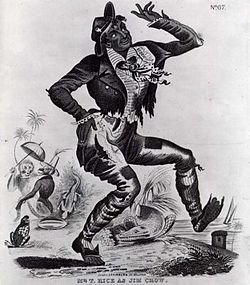

The frontispiece from Roorbach (Appendix A) might be the best place to begin, since it underlines the central premise of minstrelsy, offering whites an imaginary privileged look at the secret life of blacks. As in any theatrical performance, a suspension of disbelief is required on the part of the audience, but in the case of minstrel performances, the desired illusion depends upon a most peculiar sort of doublethink: purportedly "authentic" black characters are being portrayed by white "delineators" of Negro life as an entertainment. LeRoi Jones's comment that black music before jazz, in its successive appropriations of older white and black styles, "was almost like the picture within a picture, and so on, on the cereal package" (110), could pointedly be extended to include both the musical and non-musical elements amalgamated into minstrelsy many years before.

1. "How Bones Became a Minstrel" (Appendix B)

The First Part of a minstrel performance consisted of a set series of songs separated by comic dialogue between end men and interlocutor. Like most other extant texts of such dialogue, the tale Bones narrates here is characterized by its seeming randomness: before it can reach its destination, it is continually sidetracked into a verbal jungle of puns and malapropisms. It is a series of miscommunications somehow adding up to a punchline. A great deal of its humor depends upon an effective rendering of Negro dialect. In language, no less than costume, burnt-cork makeup, music, and dance styles, the Negro is defined by his deviations from the audience's standards, and as such he becomes a target for ridicule.

The interlocutor is present to give dramatic expression to the "common sense" values of the white audience, but his "whiteness" is altogether ambiguous, for the end man most often has the last laugh at the interlocutor's expense. Minstrelsy carves out a comfortable middle position, so that the audience may be assured of its superiority to both ignorant slaves and sanctimonious, highfalutin professors. The prototypical straight man and fool roles crystalized within minstrelsy thus represent a socially sanctioned rhetoric of largely unconscious social processes under the guise of commercial entertainment.

The "logic" of minstrelsy as rhetoric is therefore muted and entirely subordinated to the ethos of the characterizations and the audience's belief in their authenticity. Pathos meanwhile remains a separate component, entirely absent from the comic repartee but concentrated within the sentimental songs that punctuate it, as if to balance the cruelty of the humor. The curious pattern of minstrelsy is to strictly separate the head from the heart.

"Jim Crow"

2. The First White Man" (Appendix C)

"Stump speeches" were a specialty act that quickly became an indispensable staple of the "olio," or entr'acte portion of the minstrel show, performed in front of the curtain that divided the First and Second parts. This particular example is a mock sermon, a variation of the typical send-up of politicians and pastiche of current events, though in either case the principle object of ridicule was the black orator, perhaps even the idea that blacks were capable of oratory.

The usual stump speech carefully preserved the historical forms and flourishes of oratory while reducing them to utter nonsense, but "The First White Man" never collapses into this sort of incoherence. Its point of departure is a satire upon black religion, a standard component of the black stereotype lurking in the American unconscious, and its first premise is the assertion that Adam and Eve were Negroes. At a time when it was widely held, and "scientific" studies endeavored to prove, that blacks and whites were not of the same species, such an assertion must have appeared the most preposterous idea possible.

Interestingly, the last laugh here appears to be on the white man, unfavorably cast as a frightened black man. Thematically then, the story resembles Afro-American folk tales of the "Massa John" stripe, wherein the slave relies on his own cunning to outwit the master, and the basic narrative may very well have been of black origin. Although it was not uncommon for minstrels to appropriate black folk materials indiscriminately in order to subject them to ridicule, such ambiguity as that which occurs here, probably unnoticed by performers and audiences alike, must have been rare.

3. "Old Zip Coon" (Appendix D)

The title character of this Second Part sketch (often called the Afterpiece of the minstrel show) originated in the 1840s in the song of the same title, which became one of the genre's early smash hits and went on, in instrumental form, to enter the consciousness of subsequent generations as "Turkey in the Straw." The term "coon," which Webster defines as a "vulgar term of prejudice and contempt," possibly originated with this stock minstrel character.

Returning to Jones's "cereal box" analogy with which I began, it is difficult to tell whether this sketch a black burlesque of white culture or a white parody of low black culture. "Nigger will be nigger," drawls Cuff, a blacked-up white actor in front of a romantic backdrop of a South that never was, addressing his remarks to audiences who, for the most part, have never seen actual black people. The sketch introduces the additional stereotypes of an Italian immigrant and a female impersonator in the "yaller gal" role. Built upon a romantic love triangle, as were most Second Part pieces of the minstrel era, " "Zip Coon" dances its way around the emotional powderkeg of miscegenation, but the only resulting explosion is laughter.

At certain periods in the history of minstrelsy, particularly in the 1850s when the the sectional conflict was waxing in the United States, the farce and burlesque of the Second Part gave way temporarily to sentimental melodramas of "old folks at home," which established the fortunes of Edwin P. Christy and Stephen Foster. But the years of reaction in the 1870s brought back the raucous comedy with which minstrelsy had begun.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Corbett, Edward P. J. Introduction, Rhetorical Analyses of Literary Works. New York: Oxford UP,

1969, pp. xi-xxviii.

Engle, Gary D. This Grotesque Essence: Plays from the American Minstrel Stage. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State UP, 1978.

The Entertainer: Everybody's Favorite Series No. 10. New York: Amsco Music Sales Co., ca. 1935.

Haverly, Jack. Negro Minstrels: A Complete Guide. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature House/

Gregg Press, 1969.

Jones, LeRoi. Blues People. New York: Morrow, 1963.

Roorbach, O. Minstrel Gags and End Men's Handbook. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature

House/ Gregg Press, 1969.

APPENDIX A:

Interestingly, the last laugh here appears to be on the white man, unfavorably cast as a frightened black man. Thematically then, the story resembles Afro-American folk tales of the "Massa John" stripe, wherein the slave relies on his own cunning to outwit the master, and the basic narrative may very well have been of black origin. Although it was not uncommon for minstrels to appropriate black folk materials indiscriminately in order to subject them to ridicule, such ambiguity as that which occurs here, probably unnoticed by performers and audiences alike, must have been rare.

3. "Old Zip Coon" (Appendix D)

The title character of this Second Part sketch (often called the Afterpiece of the minstrel show) originated in the 1840s in the song of the same title, which became one of the genre's early smash hits and went on, in instrumental form, to enter the consciousness of subsequent generations as "Turkey in the Straw." The term "coon," which Webster defines as a "vulgar term of prejudice and contempt," possibly originated with this stock minstrel character.

Returning to Jones's "cereal box" analogy with which I began, it is difficult to tell whether this sketch a black burlesque of white culture or a white parody of low black culture. "Nigger will be nigger," drawls Cuff, a blacked-up white actor in front of a romantic backdrop of a South that never was, addressing his remarks to audiences who, for the most part, have never seen actual black people. The sketch introduces the additional stereotypes of an Italian immigrant and a female impersonator in the "yaller gal" role. Built upon a romantic love triangle, as were most Second Part pieces of the minstrel era, " "Zip Coon" dances its way around the emotional powderkeg of miscegenation, but the only resulting explosion is laughter.

At certain periods in the history of minstrelsy, particularly in the 1850s when the the sectional conflict was waxing in the United States, the farce and burlesque of the Second Part gave way temporarily to sentimental melodramas of "old folks at home," which established the fortunes of Edwin P. Christy and Stephen Foster. But the years of reaction in the 1870s brought back the raucous comedy with which minstrelsy had begun.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Corbett, Edward P. J. Introduction, Rhetorical Analyses of Literary Works. New York: Oxford UP,

1969, pp. xi-xxviii.

Engle, Gary D. This Grotesque Essence: Plays from the American Minstrel Stage. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State UP, 1978.

The Entertainer: Everybody's Favorite Series No. 10. New York: Amsco Music Sales Co., ca. 1935.

Haverly, Jack. Negro Minstrels: A Complete Guide. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature House/

Gregg Press, 1969.

Jones, LeRoi. Blues People. New York: Morrow, 1963.

Roorbach, O. Minstrel Gags and End Men's Handbook. Upper Saddle River NJ: Literature

House/ Gregg Press, 1969.

APPENDIX A:

APPENDIX B: "HOW BONES BECAME A MINSTREL"

Interlocutor. You promised, Mr. Bones, that you would one day tell us all the facts connected with your adoption of the stage as a profession. There's no time like the present, so if you are in the mood--

Bones. Oh, yes; anything to oblige. You see it was in de good old "hard cash" times dey speaks of, when gold and silver was so plenty dat all de buttons on our coats was made of ten dollar pieces and nobody cared enough to carry it in his pocket, dat Pete Simmons and me come up on de steamboat from Natchez in search of a job. We'd worked our way along, and dere wasn't a picayune in our pockets we land upon de levee.

Int. But where were the ten dollar buttons you spoke of-- why did you not use them?

Bones. Why, you seem bossy, we would, if it hadn't been for one ting-- we hadn't. Well, as I was sayin' me and Pete make our first 'pearance on de landing, widout a picayune in our pockets, and den we conclude dat it was 'bout time to make a levy ourselves.

Int. That was sensible. Well, what did you then, sir?

Bones. De fustest man dat cum along was a chap dat was a little de wuss for licker. "Bossy," says I, "we's bofe on us dead gone broke; gib us a lift." "I'll gib you a lift," says he, and wid dat he made a grab for me, but I up and tap him on de snoot and down he go like a log; got de deadfall on him, sure! "Spar' me," says he, I'se only a flat boatman." Den I histe him, and he go away quite sober. Den I skedaddled in a panic. When I had got out of sight, "Pete," says I, "we's in a corner now; money all gone, and no credit nudder.["] Just den we come to a broker's office. A bright idear struck me. I went in. "Do you give discount here?" says I. "Certainly," says he. "Well, den," says I, "just discount me a twenty." "All right," says he, "fork over. Where's your twenty?" "O," says I, "I'll gib dat to you after I've turned dis over." "Not on discound," says he, " and dis aint de place for your kind o' operations rudder. Just you take dis banjo and go out on de side walk and gib us a song and a broke down, and de banjo's yours and all you can make by it." Dat was enuff, so I took de banjo and I go out on de sidewalk and begin to play and caper; and pooty presently a crowd cum along, and I gub all de songs and jigs I was quainted did, and de money it come rollin' in by de handful, while Pete carried roun' de hat. When I'd 'bout got tired I start to go, but jus den a gemman come up and tap me on de shoulder. "You're my meat," says he. "I want a good jiggist for my minstrel show. State your price and come along;" and dat's de way I got into de burnt cork bisness.

Int. You were just then like a pugilist when he knocks his opponent out of time.

Bones. How's dat?

Int. You made a decided hit.

Bones. O, I become werry popular after dat and day engage me as todder end man at de show. and de oder todder end man was so jealous dat he gib me jaw and I hit him, and he challenge me; but, somehow, we both of us fought shy of each oder, and de papers got up a conundrum about it. Says one feller, says he, "Why am de projected 'fair of honor tween two well known burnt corkers in dis city like do predicament of a family dat finds it difficult to pay expenses?" And what do you tink de answer was? "'Cause it is hard to make both 'ends' meet."

APPENDIX C: "THE FIRST WHITE MAN"

"'Strate am de road an' narrow am de paff which leads off to glory!' Brederen Blevers: You am 'sembled dis night in coming to hear de word and have splained and 'monstrated to you; yes youbisnand I tender to splain it as lite ob de liven day. We am all wicked sinners hea below-- it's a fack, my brederen' and I tell you how it cum. You see

'Adam was de fust man.

Ebe was de tudder,

Cane was de wicked man

'Kase he kill his rudder.'

Adam and Eve were bofe black men, and so was Cane and Abel. Now I s'pose it seems to strike yer understanding how de fust white man cum. Why, I let you know. Den you see when Cane kill his brudder de massa cum and say, 'Cane, whar's your brudder Abel?' Cane say, 'I don't know, massa.' But de nigger node all de time. Massa now get mad and cum agin; speak mighty sharp dis time. 'Cane, whar's your brudder Abel, yu nigger?' Cane now git frightened and he turn white; and dis de way de fust white man cum upon dis earth! And if it had not been for dat dar nigger Cane we'd nebber been troubled did de white trash 'son de face ob dis yer circumlar globe. De quire will sing de forty-eleventh him, tickler meter. Brudder Bones pass round de passer."

APPENDIX D: "OLD ZIP COON, An Ethiopian Eccentricity, In One Scene

CHARACTERS

ZIP COON

CUFF CUDLIP

ITALIAN MUSIC MASTER

SALLY

SCENE:-- The common room of Zip Coon's house on the Old Plantation, opening on the verandah-- the cotton and cane field beyond-- the Mississippi in the distance.

(ZIP, elegantly dressed, reading a newspaper and smoking a cigar, with his feet on a table on which are decanters and glasses. White boy presenting a huge mint julip.)

ZIP. Dere, clar you'self! (drinks) Dis brandy isn't so good as de last; (smacking his lips) shall hat to discharge my wine merchant if he don't improve, for sartin. Maybe it's my taste, but somehow 'taint half so good as de ole Jamaica massa used to gib us to wash de hoe cake down with. It's mighty comfortable to be rich, to be sure, but it's debblish tiresome to hab to keep up de dignity all de time. O, for one good old-fashioned breakdown, like we used to has when massa run de old plantation for us, and all we had to do was play de banjo and loaf. (looking right and left) Nobody looking! Maybe 'taint genteel, but here goes for a try. (walks around and sings)

Long time ago we hoe de cotton.

Grub among de canebrake, munch de sugar cane.

Hunt coon and possum by de ribber bottom,

Past and gone de happy days-- nebber come again!

Ho, hi! How de moments fly!

Get up and do your duty

While de time am passin' by!

(breakdown, throws off his coat)

Dere we knock de banjo, make de sheepskin talk,

Shout until de rafters to de chorus ring;

If de massa see us, make him walk his chalk.

Trabel libely, o'er de boards, cut de pigeon wing.

Ho, hi! etc. (Break)

(CUFF CUDLIP, with a small bundle on his shoulder and in a ragged suit, peeps in and softly enters. Throws bundle down and joins in breakdown)

(CUFF CUDLIP, with a small bundle on his shoulder and in a ragged suit, peeps in and softly enters. Throws bundle down and joins in breakdown)

CUFF. Hoe it down libely, here's nobody to fear,

De gate am off de hinges, no overseer dere;

No one in de cornfield, all de coast is clear,

Here de bell a-ringin', step up and pay your fare!

BOTH. Ho, hi! etc. (break)

CUFF. Hy'a! it's no use talking-- nigger will be nigger! (puts his bundle on table and takes chair)

ZIP. (slipping into his coat) I'll hat you know daters aint no niggahs now. I belongs to de upper crust. You'm main' yourself mighty comfortable anyhow. 'Spose you couldn't be hired to refuse a drink?

CUFF. Don't press me. (puts bottle to his mouth, takes a swig, spits it out) Bah! What sort o' stuff dat? Hoss medicine?

ZIP. Hoss medicine, you ignoramus dark, you! Dat's de genuine Otard.

CUFF. If dat's "old tod" I don't want none of it. But, say, Zip, you look as if you took de world easy; can't you gib us a job.

ZIP. You wouldn't degrade you'self by workin, would you? Well, go out dere among de white trash, den.

CUFF. I say-- I see a gran pianner dere, but what's de ole banjo-- where's de ole cremonum?

ZIP. O, dem ain't fashionable, now. You 'member when we lib in de old quarter and I took a shine to Sal Beeswax, de master's cook? Hy'a! Well-- de masa's goned away and I got his property and married Sal, and we got a darter-- black one side de fact an' white todder-- an' she won't touch nuffin' short of a piannum, and dat brings all de high-toned darkies round her, and-- and de white trash dey come round her thick as flies in a 'lasses hogshead.

CUFF. Does any of 'em git stuck?

ZIP. You bet! Here come de gal, golly, look at dat hool.

(Enter SALLY, with music and an Italian master)

MASTER. (sings) O, dulce anima de mi con amore da poca.

SAl. "O dull seems the time unto me when I want to play poker."

MASTER. Costa Diva mi figelia, la croche se ha ben travato,--

SAL. "Casta Diva." I'm sure I'd not sing if I wasn't "obligato". (aside, seeing Zip) My fader! (puts her arms about his neck)

ZIP. My darter! (embraces her) Here's old Cuff Cudlip-- don't you 'member Cuff! (Cuff attempts to embrace her too. She curtsies and passes under-- he embraces Zip instead, and is slapped.)

SAL. (sings) What magic's stealing o'er me, that mein, that nobel brow!

O, how my heart is thumping against my corsets now

If this is what de crazy chaps call "love" in poetry,

I'se ready to frow up de sponge, for a good coon am I! (goes to to piano with master)

CUFF. (sings) Now my heart with remebrance is a'wharming,

And lub all its outposts is sto-horming,

New hopes in my bosom am fo-horming,

O, how like a belas' I sigh!

I feel like a chap-fallen lover

Dat a big garden roller's past over;

I'd consider myself in clover

For to catch but a glance of her eye!

ZIP. (pulling on his kids) Put on your airs!

Here comes de company in pairs--

CUFF. O, yes, by twos and threes they come;

I'll let them see that I'm at home (takes black coat out of bundle, and puts on coat and large white kids)

SAL. (as enter company of both sexes, white and black) Walk along, stalk along! Daddy's got de gout;

Take him by de elbow, make him shake it out! (sits at piano and plays to chorus)

De gate am off de hinges, no overseer dere;

No one in de cornfield, all de coast is clear,

Here de bell a-ringin', step up and pay your fare!

BOTH. Ho, hi! etc. (break)

CUFF. Hy'a! it's no use talking-- nigger will be nigger! (puts his bundle on table and takes chair)

ZIP. (slipping into his coat) I'll hat you know daters aint no niggahs now. I belongs to de upper crust. You'm main' yourself mighty comfortable anyhow. 'Spose you couldn't be hired to refuse a drink?

CUFF. Don't press me. (puts bottle to his mouth, takes a swig, spits it out) Bah! What sort o' stuff dat? Hoss medicine?

ZIP. Hoss medicine, you ignoramus dark, you! Dat's de genuine Otard.

CUFF. If dat's "old tod" I don't want none of it. But, say, Zip, you look as if you took de world easy; can't you gib us a job.

ZIP. You wouldn't degrade you'self by workin, would you? Well, go out dere among de white trash, den.

CUFF. I say-- I see a gran pianner dere, but what's de ole banjo-- where's de ole cremonum?

ZIP. O, dem ain't fashionable, now. You 'member when we lib in de old quarter and I took a shine to Sal Beeswax, de master's cook? Hy'a! Well-- de masa's goned away and I got his property and married Sal, and we got a darter-- black one side de fact an' white todder-- an' she won't touch nuffin' short of a piannum, and dat brings all de high-toned darkies round her, and-- and de white trash dey come round her thick as flies in a 'lasses hogshead.

CUFF. Does any of 'em git stuck?

ZIP. You bet! Here come de gal, golly, look at dat hool.

(Enter SALLY, with music and an Italian master)

MASTER. (sings) O, dulce anima de mi con amore da poca.

SAl. "O dull seems the time unto me when I want to play poker."

MASTER. Costa Diva mi figelia, la croche se ha ben travato,--

SAL. "Casta Diva." I'm sure I'd not sing if I wasn't "obligato". (aside, seeing Zip) My fader! (puts her arms about his neck)

ZIP. My darter! (embraces her) Here's old Cuff Cudlip-- don't you 'member Cuff! (Cuff attempts to embrace her too. She curtsies and passes under-- he embraces Zip instead, and is slapped.)

SAL. (sings) What magic's stealing o'er me, that mein, that nobel brow!

O, how my heart is thumping against my corsets now

If this is what de crazy chaps call "love" in poetry,

I'se ready to frow up de sponge, for a good coon am I! (goes to to piano with master)

CUFF. (sings) Now my heart with remebrance is a'wharming,

And lub all its outposts is sto-horming,

New hopes in my bosom am fo-horming,

O, how like a belas' I sigh!

I feel like a chap-fallen lover

Dat a big garden roller's past over;

I'd consider myself in clover

For to catch but a glance of her eye!

ZIP. (pulling on his kids) Put on your airs!

Here comes de company in pairs--

CUFF. O, yes, by twos and threes they come;

I'll let them see that I'm at home (takes black coat out of bundle, and puts on coat and large white kids)

SAL. (as enter company of both sexes, white and black) Walk along, stalk along! Daddy's got de gout;

Take him by de elbow, make him shake it out! (sits at piano and plays to chorus)

AIR

CUFF. O, clap de kitchen, niggers,

Your music can't begin,

Pull off your coats and spencers,

Take your gloves off and sail in;

Listen to de banjo

While de old ting am in tune,

Incline your ears and listen,

And I'll gib you "Old Zip Coon!"

Taking banjo suddenly from bundle, plays-- dance changed to the old melody-- Sal leaves the piano and dances alternately with Zip and Cuff. She and they become more enthusiastic, all the rest nearly frantic, till Sal faints in the arms of Cuff, and

CURTAIN

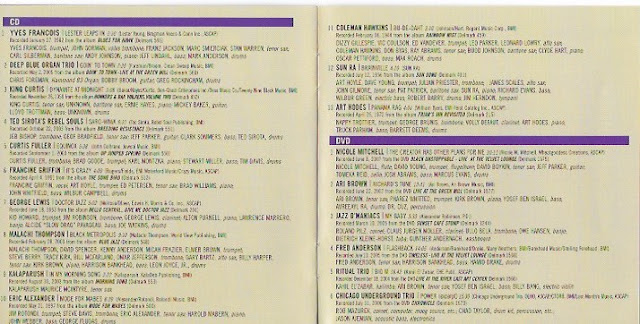

IN MY ROTATION

Lightly and Politely

In addition to the leader, this trio includes the indispensable Jim Hall and Bob Brookmeyer to create my favorite Giuffre "chamber jazz" formation. My disc is a CD-R burn from a Collectables set that also included a performance by Mabel Mercer, which I removed to make room for additional Giuffre material. The remainder of my CD-R is filled with earlier Capitol material.

Groucho as the Lord High Executioner is an inspired choices in this shortened tv version of the beloved operetta. I think of his playing similar roles in the Marx Brothers' early movies, and those who wrote their movie scores undoubtedly had a love for Gilbert and Sullivan at their roots.

I had this disc in the stack and finally played it a month ago. It's the only version of The Mikado I own, but it's enough, a pleasure to hear.

OUR CAR CLUB

Lee Morgan - trumpet

Clifford Jordan - tenor saxophone

Barry Harris - piano

Bob Cranshaw - bass

Louis Hayes - drums

NEXT:

Lightly and Politely

- Woody Shaw, Bemsha Swing (Blue Note, 1986)

One of Shaw's last great recordings, this is a perfect example of his mature lyricism. Recorded live at Baker's Keyboard Lounge in Detroit, the set brings together the local rhythm section of the young pianist Geri Allen, bassist Robert Hurst, and drummer Roy Brooks. All four solo extensively throughout.

The program is heavy on tunes by Thelonious Monk, beginning with the title song and adding "Well You Needn't" (annotator Bob Blumenthal notes that Shaw uses Miles Davis's simplified version of the bridge), and "Nutty," and Brooks's own tribute to Monk by the rhythm section only, "Theloniously Speaking" to end the set. Shaw himself contributes "Ginseng People" and "In a Capricornian Way." Allen's solo here recalls McCoy Tyner, while she herself provides the gentle ballad "Eric." The group also performs Wayne Shorter's "United," with which Shaw titled one of his 1980s LPs for Columbia, which the trumpeter proceeds to turn inside-out. Likewise, Woody tears up the only standard included here, "Star Eyes."

The program is heavy on tunes by Thelonious Monk, beginning with the title song and adding "Well You Needn't" (annotator Bob Blumenthal notes that Shaw uses Miles Davis's simplified version of the bridge), and "Nutty," and Brooks's own tribute to Monk by the rhythm section only, "Theloniously Speaking" to end the set. Shaw himself contributes "Ginseng People" and "In a Capricornian Way." Allen's solo here recalls McCoy Tyner, while she herself provides the gentle ballad "Eric." The group also performs Wayne Shorter's "United," with which Shaw titled one of his 1980s LPs for Columbia, which the trumpeter proceeds to turn inside-out. Likewise, Woody tears up the only standard included here, "Star Eyes."

- The Jimmy Giuffre 3, Trav'lin Light Collectables/ Atlantic, 1958)

In addition to the leader, this trio includes the indispensable Jim Hall and Bob Brookmeyer to create my favorite Giuffre "chamber jazz" formation. My disc is a CD-R burn from a Collectables set that also included a performance by Mabel Mercer, which I removed to make room for additional Giuffre material. The remainder of my CD-R is filled with earlier Capitol material.

"The Swamp People"

- Groucho Marx et al. The Mikado (Columbia, 1960.

Groucho as the Lord High Executioner is an inspired choices in this shortened tv version of the beloved operetta. I think of his playing similar roles in the Marx Brothers' early movies, and those who wrote their movie scores undoubtedly had a love for Gilbert and Sullivan at their roots.

I had this disc in the stack and finally played it a month ago. It's the only version of The Mikado I own, but it's enough, a pleasure to hear.

- Various Artists, The New Wave in Jazz (Impulse, 1965)

I'm sure I once owned, in the '60s, a vinyl copy, but I sprang for this CD a while back. This digital rerelease adds Albert Ayler to the mix but subtracts "Plight" "Ayler's Holy Ghosts"and "The Intellect," I suppose to allow room for unedited versions of tracks from the original. The liner notes indicate that the concert also included performances by Betty Carter and Sun Ra, but were unfortunately not recorded.

It's all from a live concert benefit in March 1965 for the Black Arts Repertory Theatre... LeRoi Jones, that is.

First up is the John Coltrane Quartet on the weird-ass Evan Ahbbez standard "Nature Boy"; Trane & Co. render the tune a mere exercise in intervals, as they take it out to God-knows-where.

But waiting in the wings is the Archie Shepp Septet, with Marion Brown on alto, Fred Pirtle, baritone sax, and trumpeter Virgil Jones. The band also featured Ashley Fennell, trombone; the estimable Reggie Johnson on bass; and Roger Blank on drums. Many names here are rarely spoken of, but boy-o-boy. The crown jewel of the entire disc is their thrilling version of Shepp's "Hambone," an utterly cosmic set of variations on multiple themes and a chorus to raise the hairs on one's neck. Masterful.

"Hambone"

The disc then introduces the Charles Tolliver Quintet, featuring James Spaulding, Bobby Hutcherson, Cecil McBee and Billy Higgins.

Theirs was undoubtedly the first version I ever heard of Monk's "Brilliant Corners," a slyly marvellous rendition. Their set also features Tolliver's "Plight."

- Ornette Coleman, Ornette at 12 and Crisis (Impulse/ Real Gone Music, 1968 and 1969)

- John Lewis, The Golden Striker and Jazz Abstractions (Atlantic/ Collectables, 1960 and 1961)

- Gary Peacock, Tales of Another (ECM, 1977)

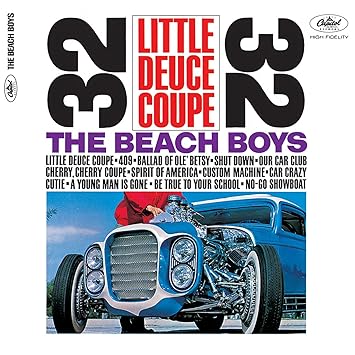

- The Beach Boys, Little Douce Coupe and All Summer Long (Capitol, 1963 and 1964)

OUR CAR CLUB

- Lee Morgan, Take Twelve (Jazzland, 1962)

- "Raggedy Ann" - 6:46

- "A Waltz for Fran" - 4:55

- "Lee-Sure Time" - 8:27

- "Little Spain" (Jordan) - 7:45

- "Take Twelve" (Elmo Hope) - 4:55

- "Second's Best" - 7:08

- "Second's Best" [alternate take] - 7:29 Bonus track on CD reissue

- All compositions by Lee Morgan except as indicated

NEXT: