Grammar, on the other hand, allows speakers of a language to express thought and enables thought to be understood, by oneself as well as others. It is absolutely essential to language as communication and hence to our existence as human beings. We learn grammar as we learn to speak, not in a classroom.

With this distinction in mind, I wish to attack a common pedagogical assumption which has held sway in the teaching of English over at least the past thirty years, namely that the teaching of the rules of grammar, as such, is useless and even harmful to the teaching of writing. The foremost proponent of this view in the U.S. is nothing less than the National Council of Teachers of English.*

To the NCTE, it has become almost an article of faith to leave grammar (by which, as we shall see, appears to mean both grammar and usage) out of the curriculum. I will here present some of what professes to prove the benefits of not teaching grammar.

I strongly disagree with the NCTE position and insist that the contrary is true: Ignorance of the rules not only impedes the teaching of writing; it also impedes the teaching of reading.

(Just a short anecdote before I proceed, from the late years of my own teaching career: The issue of the teaching of grammar came up once in an English department meeting, and I voiced my disagreement with the NCTE prescription, to no reply. In attendance was an assistant principal named Marty, and sure enough a fake E-1 notice, the last warning before "termination," appeared in my office mailbox. Hmmmm.)

Here is the result of a search ("teaching grammar") on the NCTE website:

Unfortunately, one cannot gain access to these pedagogical secrets without a paid membership in the NCTE. They seem to be the sole proprietor of everything in their private library. Now I can see that I'm up against an industry (i.e. a vested interest) dedicated to a false claim. There is obviously more to the proscription of grammar than what research dissertations purportedly prove.

|

| The good old days. Let's make America great again! |

It appears one must do a Google search to make headway online. Here are three examples I thought looked promising:

1. The Atlantic, Feb. 2014: Michelle Navarre Cleary, "The Wrong Way to Teach Grammar"

At last, I have discovered an actual text. And incidentally I find an ad at the Atlantic site that offers a free download, Grammarly, that promises to "[make] sure your writing is easy to read, effective, and mistake-free." Apparently, the ultimate solution of the problem of not knowing how to write is to have your computer do it for you. The unspoken assumption of this ad is that good writing is hard, not at all a dreamy episode of letting it all hang out, as the Atlantic article proposes. And that is the truth.

Here are the article's main assertions and their warrants:

Before undertaking a rebuttal, let's explore some of the article's links.

The first link leads to a blurry view of highlighted selections from a Handbook of Research in Teaching the English Language Arts and a c.v. of its author, but nothing else; continuing along the links, we are destined to fall into the rabbit hole of another Google search, from which we arrive at an advertisement for the book (cosponsored by the International Reading Association and-- you guessed it, the NCTE), but no substantive text. We'll have to try again.

Ms. Cleary's 1984 link leads us to an advertisement for an issue of the American Journal of Education and a short description of its contents: there is not a word in it referring to the teaching of grammar.

Her name is Kellyanne Conway.

1. The Atlantic, Feb. 2014: Michelle Navarre Cleary, "The Wrong Way to Teach Grammar"

At last, I have discovered an actual text. And incidentally I find an ad at the Atlantic site that offers a free download, Grammarly, that promises to "[make] sure your writing is easy to read, effective, and mistake-free." Apparently, the ultimate solution of the problem of not knowing how to write is to have your computer do it for you. The unspoken assumption of this ad is that good writing is hard, not at all a dreamy episode of letting it all hang out, as the Atlantic article proposes. And that is the truth.

Here are the article's main assertions and their warrants:

- The author's personal teaching experience confirms that students' nervousness about writing stems from their teachers' vain attempts to instill grammar.

- "A century of research shows that traditional grammar lessons—those hours spent diagramming sentences and memorizing parts of speech—don’t help and may even hinder students’ efforts to become better writers. Yes, they need to learn grammar, but the old-fashioned way does not work."

- This finding-- confirmed in 1984, 2007, and 2012 ... is consistent among students of all ages... [One] well regarded study followed three groups of students from 9th to 11th grade [two of which received grammar instruction and one that did not]. The result: No significant differences among the three groups-- except that both grammar groups emerged with a strong antipathy to English."

- "... [W]e need to teach students how to write grammatically by letting them write. Once students get ideas they care about onto the page, they are ready for instruction-- including grammar instruction-- that will help communicate those ideas."

Before undertaking a rebuttal, let's explore some of the article's links.

The first link leads to a blurry view of highlighted selections from a Handbook of Research in Teaching the English Language Arts and a c.v. of its author, but nothing else; continuing along the links, we are destined to fall into the rabbit hole of another Google search, from which we arrive at an advertisement for the book (cosponsored by the International Reading Association and-- you guessed it, the NCTE), but no substantive text. We'll have to try again.

Ms. Cleary's 1984 link leads us to an advertisement for an issue of the American Journal of Education and a short description of its contents: there is not a word in it referring to the teaching of grammar.

The 2007 link connects to something more substantial: a 31-page article in the Journal of Educational Psychology by Dolores Perin, followed again by a huge bibliography. Within the article, one finds only two explicit references to the teaching of grammar; both negatively compare it to the activity of "combining sentences." There is, however, no explanation of how this can be done without such grammatical concepts as compound and complex sentences or an awareness of various types of phrases and subordinate clauses. The article, moreover, is unlikely to be of use to anyone other than doctoral candidates who can navigate its nearly impenetrable mass of obscure methodologies and arcane vocabulary; it is rather like the ink the octopus excretes to obscure its position (I never did care much for most academic writing). No one who is engaged in the process of actually teaching students to write would have any use for such a study.

Her name is Kellyanne Conway.

Wrong!

Finally, the 2011 link connects to the website of the American Psychological Association, which contains an abstract of another article (Graham, et al. "A Meta-analysis of Writing Instruction for Students in the Elementary Grades") from the Journal of Educational Psychology. For the full text of the article, unfortunately, one must again shell out for a pdf download from the Journal. By itself, the abstract contains no reference to the teaching of grammar.

The study link refers to an article (Elley, et al. "The Role of Grammar in a Secondary School Curriculum") posted on the ERIC website, taken from a 1979 piece published under the auspices of the NCTE. Once more, we find ourselves reading a short abstract (the complete article will cost a few dollars). The abstract posits that, while "a textbook based program that focussed on traditional grammar" produced a negligible effect on students' writing, "the Oregon Curriculum without the grammar thread... but with extra reading and creative writing" was "more positive." Unfortunately, it is impossible to judge this claim knowing neither the Oregon Curriculum nor the methodology and extent of the study.

Continuing to follow the links that are not outdated, we are led to studies of varying lengths, none of which refer explicitly to the teaching of grammar. One of them (Thomas Flynn and Mary King, eds., Dynamics of the Writing Conference, 1993) contains an article which, from the book's index, appears to investigate the subject, but is actually about usage, specifically about African American dialect and the use of verbs. In short, none of the citations in Ms. Cleary's article support her main thesis, that the teaching of grammar is ineffective or harmful to students' writing.

One of the author's remaining claims is supported by observations taken from her own experience of eight years teaching remedial writing (or so I presume) at the college level. The other is a sweeping generalization concerning the efficacy of teaching grammar. Based on my experience teaching remedial writing at Purdue University Calumet, as well as a long career teaching language arts at the high school level, here are some observations of my own.

- What Ms. Cleary describes as her students' problem appears to fall into the categories of usage and punctuation, not grammar: "In my work with adults... I have found over and over again that they over-edit themselves from the moment they sit down to write. They report thoughts like "Is this right? Is that right? and "Oh my God, if I write a contraction, I'm going to flunk." My own experience, also with adults, was in a remedial class, not exclusively of former drop-outs, but rather a larger group who were unable to pass a writing competency test, in the form of an essay responding to a particular prompt. Most of them continued to be enrolled in other classes, but a few had taken the test every semester for four or five terms; one was a woman in her sixties, chasing a degree. Yes, there were often usage problems, many stemming from misuse of the principal parts of verbs. A few of them, however, were unable to differentiate a complete sentence from a fragment or a run-on. Others wrote as fourth or fifth graders might: short, simple sentences, producing a choppy mess that failed to achieve the minimum count of words demanded by the test. The same students usually had trouble reading sentences longer than ten or twelve words. I found that it was indispensable for a writer to create a subject and verb when he or she began to organize thoughts into meaningful sentences. Likewise, it was essential that they recognize various sentence structures. This required an understanding of the rules of grammar. Ms. Cleary confuses the issue: nobody maintains that a prewriting exercise of some sort should not be the very first step in creating a piece of writing, yet Ms. Cleary seems to imply that teachers wrongly force structure, usage, and style points on students before they even have their ideas down on paper in the form of diagrams, outlines, or whatever. She seems to be attacking a straw position which no experienced writing teacher or coach would ever employ in a classroom.

- "We need to teach students how to write grammatically by letting them write," Ms. Cleary concludes, without giving an example of what she means. On its face, it appears to be a circular argument. She ends by slamming us damned sentence-parsers as being grounded by nostalgia (for what she doesn't say), rather than research.

2. Valparaiso University

Here I find, to my surprise, not another proscription against the teaching of grammar, but instead a set of recommendations for various strategies for its incorporation. Apparently, Heather Zaharias, its author, was unaware of the research proving its negative effects. No rebuttal is necessary.

3. Heinemann 1991 asserts:

"Research over a period of nearly 90 years has consistently shown that the teaching of school grammar has little or no effect on students." Following this sweeping statement is a mighty-looking fortress of bibliography, all this under the heading of "Facts." Curiously, this behemoth list of sources and perky quotations contains no references before 1959, which is hardly ninety years. I would be willing to take aim against any of Heinemann's sources, but unfortunately there are few links, and none of them are operational.

The names on top, George Hillocks and Michael Smith. appear to be the twin gods of the dogma I have been questioning. Attributed to various experts, here are a few of Mr. Heinmann's choices which are just plain silly:

- "Diagramming sentences... teaches nothing beyond the ability to diagram."

- "If schools insist upon teaching... concepts of traditional grammar (as many still do), they cannot defend it as a means of improving the quality of writing."

- "Studying formal grammar is less helpful to writers than simply discussing grammatical constructions and usage in the context of writing."

- "Teach only the grammatical concepts that are critically needed for editing writing and teach these concepts and terms mostly through mini lessons and conferences while helping students edit." (my emphasis)

Rebuttal: I promise to keep it short.

1. My own experience as a K-12 student and my children's affirmation, that learning to recognize sentence structures, label them, and work with them was an essential part of graduating and continuing to succeed as students at the next level and beyond.

2. The notion that teaching grammar can be incorporated entirely into the process of editing is completely counter-intuitive. Reading, essentially, is an analysis of the written word, while writing is a synthesis to create it. Presumably, our aim is to add to the complexity of both at a certain point of a child's education. One need not retain diagrams of compound-complex sentences with all the trimmings, but when reading, one needs to recognize them and differentiate between independent and subordinate clauses.

3. Terminology is important in teaching any subject, as is precision. Improvements in our writing do not happen overnight or by some vague method of imbibing them. They require attention, hard work, and they happen gradually, little by little, so that at each successive grade level, students grow as writers. This means that grammar instruction should be a steady part of a child's learning beginning in the middle grades and continue through graduation.

4. What concerns me most is that when we are commanded not to teach grammar "in isolation," we are really being given an excuse not to teach grammar at all. Chances are that at least one generation of teachers has somehow muddled through their own education without digesting English grammar. They don't know how to teach it, because nobody bothered to teach them.

One final comment: a political slant. And then I'll shut up. I take seriously George Orwell's contention that slovenly language and slovenly thought exist in a symbiotic relationship. It is also instructive to read his forecast of the future of the English language, Newspeak, actually a parody of the abuse of language the first essay takes on.

Politics and the English Language

Principles of Newspeak

*Just dropping the name NCTE reminds me of the few years when I was a dues-paying member. Aside from the fancy conferences they sponsor annually, with hundreds of industry vendors standing by, I remember the quarterly journal they sent to aid me as an English teacher. In all the issues I received there was not an article even remotely related to what actually happened in classrooms at Gage Park High School.

In my rotation:

- Duke Ellington, All American in Jazz/ Midnight in Paris (originally Columbia, 1962; Essential Jazz Classics reissue, 2013)

Until this first-ever CD release of All American, I considered it among the least compelling Ellington recordings of the '60s. I now realize this was because I was listening to a poorly-recorded cassette copy of the late Don Miller's original LP. Now that I can hear it properly, I am able to overlook the varying quality of the tunes (all taken from the Broadway musical of the same name), and focus instead on its ingenious arrangements, all but two of which have been confirmed as Billy Strayhorn's, for the Ellington band.

All in all, this is not a very memorable score; I vaguely remember the brief popularity of "Try to Remember," but none of the rest strikes a chord at all.

All in all, this is not a very memorable score; I vaguely remember the brief popularity of "Try to Remember," but none of the rest strikes a chord at all.

Still, I would characterize this project as the "Ellingtonization" (actually, the "Strayhornization") of someone else's bag, much in the manner of their treatment of The Nutcracker the previous year, and future projects like Recollections of the Big Band Era.

The release also includes Midnight in Paris, not to be confused with Duke's soundtrack for Paris Blues a little earlier in the decade. This project, too, relies on clever arrangements to give some overused Parisian themes a little goose, in the Ellington manner. A handy little booklet includes the original liner notes for both LPs.

- Gram Parsons, GP/ Grievous Angel (Reprise, 1972, 1973)

On an earlier post I took up a two-disc compilation covering Parsons's entire, albeit short, career. This single disc pairs his first recordings under his own name, after leaving the The Flying Burrito Brothers.* The two LPs were released a year apart, GP in January 1972, and Angel the following January, a few months before Parsons's death.

GP was recorded at Wally Heider's Studio 4 in Hollywood. Gram Parsons remains a top-notch lyricist, alternately sensitive and assertive. He puts on a whole sub genre of country pop with "Kiss the Children," wherein yet another drunk, apparently still on his barstool, laments the woman gone for good with their kids:

"And the gun that's hanging on the kitchen wall, dear,

It's like a road-sign pointing straight to Satan's cage."

Emmylou Harris contributes mightily here in many duets with Parsons.

GP was recorded at Wally Heider's Studio 4 in Hollywood. Gram Parsons remains a top-notch lyricist, alternately sensitive and assertive. He puts on a whole sub genre of country pop with "Kiss the Children," wherein yet another drunk, apparently still on his barstool, laments the woman gone for good with their kids:

"And the gun that's hanging on the kitchen wall, dear,

It's like a road-sign pointing straight to Satan's cage."

Emmylou Harris contributes mightily here in many duets with Parsons.

Emmylou figures large as well on Grievous Angel, which features a much larger contingent of sidemen than its predecessor. Guest vocalists include Linda Ronstadt, singing backup on the album's closer, and Bernie Leadon. An amusing highlight is a medley concocted in the studio, disguised as a fictitious "live" performance in Northern Quebec: shades of The Beach Boys Party!

*not to be confused with The Traveling Wilburys.

The provenance of these recordings must have been unearthed fairly recently, as my sole reference, W. E. Timner's Ellingtonia: The Recorded Music of Duke Ellington and His Sidemen, does not list this concert, though it does note another appearance of Ella and Duke's in Stockholm early in the year.

Ella is at her absolute best in front of an enthusiastic audience, like the one on this recording. One can imagine her facial expressions as she scats and growls her way through Só Danço Samba and Cotton Tail.

Most of the tracks feature Duke's orchestra with Jimmy Jones, Ella's regular accompanist, at the piano; but as always, Ellington makes his presence felt swinging the band through "Imagine My Frustration," "Duke's Place" (wherein Johnny Hodges and Paul Gonsalves both take solo turns), and the glorious closing "Cotton Tail," with Gonsalves returning to trade fours with Ella.

- Captain Beefheart, Mirror Man Sessions (Buddha, 1967)

I've owned the original Mirror Man LP since it first appeared, four years after it was recorded; chronologically, it would fit between the albums Safe as Milk and its follow-up, Strictly Personal. (The original gatefold cover was cut in such a way as to present Beefheart within a broken mirror.)

Originally there were only four tunes-- "Tarotplane," "25th Century Quaker," "Mirror Man," and "Kandy Korn," all long workouts that sounded more like demos than material for release. The CD reissue adds five tracks, much more concise, that sound like they were meant to be heard. These tunes all stick in my mind, especially "Gimme Dat Harp Boy" and that instrument's furious demonstration by one of its all-time masters.

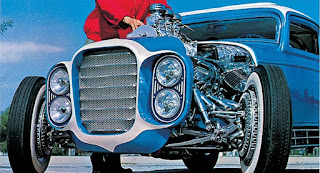

OUR CAR CLUB

IN MY CAHHH

Insurrection in the ranks: off with their heads!

Discs that I have not played much are getting the heave-ho to make room for: Thirty-seven promotions and demotions, in all.

Here are a few of the new arrivals:

Next: Latter-Day Captain Beefheart

Insurrection in the ranks: off with their heads!

Discs that I have not played much are getting the heave-ho to make room for: Thirty-seven promotions and demotions, in all.

Here are a few of the new arrivals:

- Caetano Veloso, Livro (Nonesuch, 1998)

- Dexter Gordon, Doin' Allright (Blue Note, 1961)

Next: Latter-Day Captain Beefheart

No comments:

Post a Comment